Introduction

Human health is influenced by multiple environmental and individual factors. Social and environmental determinants appear to have an influence on health behavior in general, that is, on the risks and precautions people take regarding their health (Diez Roux, 2001). More specifically, it has been observed that in neighborhoods with an unfavorable socioeconomic situation, risky behavior regarding health, particularly alcohol use, is more frequent (Chang & Cañizares, 2010; Fone, Farewell, White, Lyons & Dunstan, 2013; Jones-Webb, Snowden, Herd, Short & Hannan, 1997), and alcohol sales are higher (Duncan, Duncan & Strycker, 2002). These areas also display higher rates of mortality linked to alcohol (Dantzer, Wardle, Fuller, Pampalone & Steptoe, 2006), particularly among youth in urban areas (Erskine, Maheswaran, Pearson & Gleeson, 2010). However, other authors state that neighborhoods with greater purchasing power show a greater quantity and frequency of alcohol consumption (Galea, Ahern, Tracy & Vlahov, 2007), and that the role played by the neighborhood in consumption among at-risk populations such as youths is unclear (Brenner, Bauermeister & Zimmerman, 2011). Studies on animal models indicate that environmental stress decreases alcohol consumption, though this is a complex relationship involving numerous factors (Becker, Lopez & Doremus-Fitzmater, 2011). This complex relationship may also exist in social and environmental characteristics as they may operate as environmental stressors linked to a decrease in alcohol use.

At the same time, individual social characteristics, such as inequality relating to income level and gender, translate into a greater predisposition to certain illnesses, particularly non-transmissible ones (Etienne, 2013). In addition to organic or physical diseases, this group includes mental illnesses that are also sensitive to social determinants (Stockdale et al., 2007), particularly in middle-income countries such as Argentina (Mullings, McCaw-Binns, Archer & Wilks, 2013).

As regards individual socioeconomic level, it appears that higher poverty levels increase exposure to environmental stressors that influence mental health (Mullings et al., 2013). At the same time, the socioeconomic level of both the individual and neighborhood are linked to the use of other psychoactive substances, in addition to alcohol (Redonnet, Chollet, Fombonne, Bowes & Melchior, 2012; Simons et al., 2005). Neighborhoods with a high crime rate display more criminal behavior, and concomitantly higher use of illicit psychoactive substances and alcohol (Fuentes, Alarcón, García & Gracia, 2015; Hawkins, Catalano & Miller, 1992). At the same time, risky alcohol use is associated with a higher probability of using multiple psychoactive substances (Kuntsche, Rehm & Gmel, 2004; Midanik, Tam & Weisner, 2007), while the prevalence of psychoactive substance use is greater among persons with an alcohol-related disorder (Martin, Kaczynski, Maisto & Tarter, 1996). Nevertheless, this link is unclear (Smart & Ogborne, 2000).

As regards gender, in other Latin American countries it has been found that environmental characteristics produce different effects on the mental health of both men and women. Among men, there is a predominantly greater exposure to risky behavior (Mullings et al., 2013), whereas among women the different income translates into a higher rate of non-transmissible diseases (Etienne, 2013). Moreover, the degree of deprivation of the neighborhood has a different effect on risky alcohol use patterns, depending on gender (Fone et al., 2013).

In Argentina, the population with the highest prevalence of alcohol and other psychoactive substance use is college students, particularly men (Observatorio de Drogas Argentino [Argentine Drug Observatory], 2005; 2010; 2011). Nonetheless, few studies address the environmental and individual characteristics of this behavior or its link with mental health or the problems experienced by these youths. Moreover, reviews of this topic have indicated a lack of studies that consider both environmental and individual variables to interpret the role of environmental characteristics (Jackson, Denny & Ameratunga, 2014). Accordingly, this study seeks to evaluate the existence of hierarchical links in the prediction of alcohol-related problems between socio-demographic characteristics, use of alcohol and other psychoactive substances, based on environmental characteristics. This hierarchical structure was evaluated among college students in the city of Mar del Plata, Argentina, also taking gender into account as a possible moderating variable. The following environmental characteristics that could be considered environmental stressors were selected: overcrowding rate by home, which is used as an indicator of neighborhood poverty (Galobardes, Shaw, Lawlor, Lynch & Smith, 2006), and crime rate (since it has been observed that substance use is greater in neighborhoods with a higher crime rate). The individual socio-demographic characteristics considered were individual socioeconomic level, age, and gender.

Method

This was a non-experimental, cross-sectional, co-relational study. To minimize classification bias, precautions such as avoiding links between data collectors and participants, using a structured self-administered questionnaire, ensuring anonymity, and concealing the work hypothesis were taken.

Participants

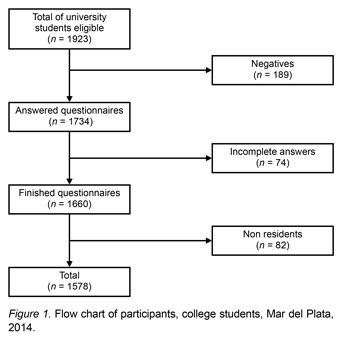

A random sampling was carried out by clusters of college students from all degree courses at a national public university in Mar del Plata. The procedure used consisted in assigning a number to each subject taught at the college and selecting one subject a year for the first three years using a random number generator. The questionnaire was applied to all students present in the classes for the subject chosen. The selection criteria was being a regular student with permanent residence in the city. A total of 1,578 students (59% female) took part, with a response rate of 88%. Reasons for exclusion are given in Figure 1. Data collection was carried out between April and November 2014. Ninety per cent of the students had consumed alcohol in the previous year. The remaining descriptive data can be found in Table 1.

Instruments

Alcohol-related problems

These were identified using the International Composed Diagnostic Interview (CIDI) (Robins et al., 1988), in its original version, which has demonstrated good psychometric properties in various contexts (Tacchini, Coppola, Musazzi, Altamura & Invernizzi, 1994), which is still currently the case (Kessler & Üstün, 2004). The number of criteria to diagnose alcohol-related disorders compatible with the latest version of the Mental Disorder Diagnostic and Statistical Manual (DSM-5) (American Psychiatric Association, 2013) met in the previous 12 months was taken into account. This was a quantitative variable, consisting of the sum of the criteria met (values between 0 and 11).

Regular alcohol consumption

The study calculated the amount (number of standard units, i.e., any drink with 11 grams of pure alcohol, drunk per occasion) and typical frequency (daily = 10, almost daily = 9, 3 to 4 times a week = 8, 1 to 2 times a week = 7, 3 to 4 times a month = 6, approximately once a month = 5, 6 to 11 times a year = 4, 1 to 5 times a year = 3, never in the previous year but had drunk before that = 2, and never = 1) of regular alcohol use in the previous 12 months.

Use of other psychoactive substances

The study determined whether a person had used other psychoactive substances in the previous year, and if so, he/she was asked to indicate which from a list including cannabis, hallucinogens, sedatives (benzodiazepines), stimulants such as amphetamines, cocaine, opioids, and others (excluding medically prescribed substances). This was used to calculate the number of psychoactive substances each participant had used (values between 0 and 7).

Socioeconomic factors

The individual socioeconomic level was established using the Graffar Scale adapted to the Latin American population (Castellano & de Méndez, 1994). The raw score with a scale of 4 to 16 was used. A higher score indicated a lower socioeconomic level. The age (in years) and gender of the participants were also obtained.

Environmental stressors

On the other hand, participants were asked about the place they lived in the city (neighborhood, n = 54) in order to determine the overcrowding rate (by dividing the number of inhabitants of the neighborhood by the number of houses) and the crime rate (number of crimes reported in each neighborhood per 1,000 inhabitants) in 2014 (i.e., during the data collection period), based on official statistics available at http://gis.mardelplata.gob.ar/app_mapa_delito

Procedure

Students were recruited in the classrooms where the subjects were taught. Data were collected during class hours, and the questionnaire took approximately 20 minutes to be administered. The questionnaires were applied by four researchers (psychologists or advanced psychology students) with over five years experience in the topic; they were present at all times to clarify any doubts. The project had the approval of the Ethics Committee of the Instituto Nacional de Epidemiología Dr. Juan H. Jara (National Epidemiological Institute). Participation was voluntary and anonymous, and involved the informed consent of all the participants. Students were given a general information sheet on the study and means of contacting the persons conducting it, and information on treatment centers for alcohol-related problems.

Data analysis

First, lost data were imputed using the MICE (Multivariate Imputation by Chained Equations) package of the R 3.3.1 software (van Buuren & Groothuis-Oudshoorn, 2011). Using a multiple imputation method, data missing from the variables were completed: usual amount of alcohol used (3%), individual socioeconomic level (12%), age (2%), gender (1%), overcrowding, and crime rate (18%) The distributions before and after imputation were similar.

First of all, preliminary analyses, both descriptive and correlative (Spearman method), were carried out to explore the relations between the various variables. For gender, a non-parametric test was used (Mann-Whitney U) to estimate differences between the two groups. Given the possible hierarchical structure of data, i.e., the links between individual predictors and alcohol-related problems could differ based on the characteristics of the neighborhood, the researchers evaluated the need for carrying out multilevel modeling with inter-class correlation (ICC), and calculating the design effect. As regards sample size, it was recommended that this type of analysis consisted of over 50 groups at Level 2 (Maas & Hox, 2005), a condition that this study met (Level 2 = neighborhood characteristics). The construction of the model followed the following sequence:

M0: null model, simple regression of alcohol-related problems.

M1: simple multilevel models of random effects (Level 2) for environmental stressors and socioeconomic level, comparing the inclusion of each one.

M2: random effects model selected in M1 (Level 2) and fixed effects model of (Level 1), comparing the inclusion of each of these individually.

M3: model of random effects and fixed effects selected in M2, indicating gender as a random slope effect in order to permit different relations between predictors of fixed effects in women and men, in other words, to evaluate the possible differences in association (positive, negative or null) between predictors based on the values of the gender variable.

Multilevel analyses were conducted using the nlme Package of R 3.3.1 software (Holmes, Bolin & Kelley, 2014). To estimate the model, Restricted Maximum Likelihood (REML), the maximum number of iterations = 100 and optimizer = optim were used, and for the selection, the observation and testing of the adjustment rates was used with an χ² test (Anova function). Before their inclusion in the model, all the variables were adjusted to the same scale and centered with the scale function, thus ensuring the comparison of β coefficients. The linear adjustment and normalization of residuals were studied using the qqnorm and histogram functions. The final model was repeated, including only drinkers (N = 1413).

Results

Preliminary analyses

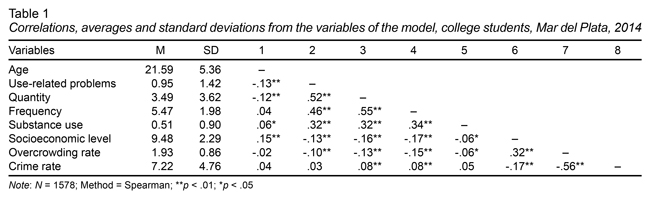

According to Table 1, almost all the variables considered (except for the crime rate) were related to alcohol-related use, mainly using regular quantity and frequency, and the use of other psychoactive substances.

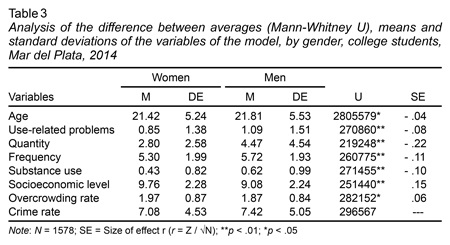

As regards differences by gender, almost all the variables, with the exception of crime rate, displayed significant differences. The greatest differences (by effect size) were observed in the variables of regular amount used and socioeconomic level, and the smallest were in age and overcrowding rate.

Environmental stressors and socioeconomic level

Differences were identified between the null model M0 (AIC = 4487, BIC = 4483, Likelihood Ratio = -2241, constructed with the Generalized Least Square) function and hierarchical models (function Linear Mixed-Effects) M1a (random effect = overcrowding rate, AIC = 4483, BIC = 4499, Likelihood Ratio = -2238, p < .001) and M1c (random effect = socioeconomic level, AIC = 4482, BIC = 4499, Likelihood Ratio = -2239, p < .001). At the same time, variations were observed in alcohol-related problems in M1a (ICC = .13, Design Effect = 4.67) and M1c (ICC = .12, Design Effect = 15.45), indicating the need to perform a multilevel analysis. The M1a and M1c models were very similar (p = 1), therefore, depending on the degree of variability explained (13%) and the number of groups (> 50), the variable of overcrowding rate was selected as the random effect. This is the model explained below.

Overcrowding rate, socioeconomic level, usual amount and frequency of alcohol use, use of other psychoactive substances, gender and age

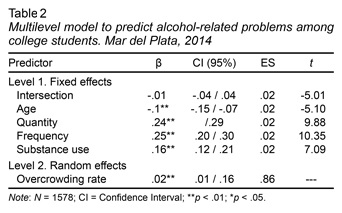

In the M2 model, the overcrowding rate was used as a random effect variable, and each predictor of fixed effects (i.e., socioeconomic level, habitual quantity, and frequency of alcohol consumption, use of other psychoactive substances, gender, and age) was estimated individually. All of them were statistically significant (p < .01). They were then included in the model one by one. In the final model, gender (p = .39) and socioeconomic level (p = .12) were not significant, and were therefore removed as predictors. The final model is presented in Table 2.

Level 1 of M2 explained 23% (R2 = .23) more than what was estimated for M1a; in other words, this model explained 36 % of the alcohol-related problems. The overcrowding rate still accounted for 13% of the variance observed (R2 = .13), despite the inclusion of the predictors of Level 1. The final model presented a linear adjustment and suitable normality of residuals, and its replication including only drinkers produced almost identical results.

Moderating effect of gender

Finally, although it was ruled out as a direct predictor, the role of gender was estimated as a possible moderator, because of the differences found in the various variables (Table 3). The model obtained in the previous step was added as a random slope effect (M3). No differences were identified between M2 (AIC = 4045, BIC = 4083, Likelihood Ratio = -2016) and M3 (AIC = 4048, BIC = 4097, Likelihood Ratio = -2015, p = .86).

Discussion and conclusions

Given the characteristics of alcohol use among college students, and the limited knowledge regarding its link with environmental characteristics, the purpose of this article was to determine whether two environmental stressors (characteristics of neighborhood, one relating to poverty, the overcrowding rate, and the other to violence, the crime rate), play a role in the link between individual characteristics (individual socioeconomic level, regular use of alcohol and other substances, age, and gender) and alcohol-related problems.

Whereas some studies (Chang & Cañizares, 2010; Jones-Webb et al., 1997) found that neighborhoods with a higher overcrowding rate, which are consequently more underprivileged, display lower alcohol use, in others, the opposite was found (Galea et al., 2007): lower use in neighborhoods with greater purchasing power. Our results coincide with the former; psychoactive substance use is slightly lower in neighborhoods with less purchasing power. However, the correlation rate was low, questioning the existence of a link. Additional studies could clarify this issue. Moreover, a hierarchical structure was observed that indicated that the overcrowding rate was the main environmental predictor of alcohol-related problems, and responsible for a part of the variability of the final model with fixed predictors.

Unlike in other contexts (Hawkins et al., 1992), the crime rate was not linked to the use of other psychoactive substances. This may be due to the characteristics of the population studied, as the use of psychoactive substances is extremely common (Observatorio Argentino de Drogas, 2005), or to the type of indicator, as there could be different trends in certain neighborhoods as regards to reporting crimes.

Another result that contradicted the literature (Redonnet et al., 2012; Simons et al., 2005) was that a lower individual socioeconomic level was related to a lower use of other psychoactive substances. This link was weak and should be viewed with caution. New studies could clarify whether this relation exists among other populations of college students, and possible differences regarding other populations. Individual socioeconomic level was also linked to the amount and frequency of alcohol use, which, in accordance with previous studies (Kuntsche et al., 2004; Midanik et al., 2007) was linked to the use of other substances. However, the evaluation of various models failed to suggest that socioeconomic level played a role as a direct or indirect predictor of alcohol-related problems.

As was recorded in the literature, differences were observed in environmental and individual socioeconomic conditions, and in the characteristics of the use of alcohol and other psychoactive substances, based on gender (Diez Roux, 2001). However, the inclusion of gender as a direct predictor and moderator was not significant. One could hypothesize that beyond gender differences in specific consequences of alcohol consumption (Hunt, 1993; Rose & Grant, 2010), alcohol-related problems are mainly linked to social differences between men and women. That is to say, gender roles that encourage greater consumption of alcohol and other substances among men, and women’s residence in lower income neighborhoods, are relevant factors in the number of alcohol-related problems displayed, beyond the condition of being male or female.

Although these results represent a progress in the field, they should be considered within the context of certain limitations. First, individual socioeconomic variables, overcrowding, and crime rates had a high percentage of imputation. This can be explained by the fact that socioeconomic level is a composite rate, and the fact that overcrowding and crime rates being obtained from the question on the neighborhood in which they live, which might be unknown. However, the percentages of lost data were within the usual number for Psychology studies (Enders, 2003), and the variations were similar before and after imputation. On the other hand, since the socioeconomic and cultural characteristics of the country of origin affect many of these relationships (World Health Organization, 2014), they cannot be generalized to other contexts. Moreover, it is important to compare these results with higher education establishments, and to include variables linked to the particular school environment of the sample. Although this study makes it possible to observe how current conditions are linked to people, in the future it would be interesting to research the chronicity of the exposure or how the influence of environmental stressors, depending on the stage of the exposure (such as puberty and childhood), has operated in relation to other stressors. It would also be useful to study these relations in greater depth in various consumption groups, or on the basis of the degree of severity of the alcohol-related disorder.

One clear conclusion of this work is that, although at least one environmental condition predicts the problems caused by alcohol, the amount and frequency of alcohol use, followed by the use of other psychoactive substances, were the strongest predictors among college students. In this regard, notwithstanding broader measures to improve the population’s environmental conditions, there is a need for various initiatives to be implemented and sustained to reduce alcohol use.