Introduction

The role of daily social environment, added to stressful life events, would have the capacity to destabilize an individual, connoting physiological, emotional, cognitive, and behavioral demands against which violent behavior is assumed as one of the multiple sets of possible answers (Faasse & Petrie, 2015). The crisis of the family as a formative institution of positive values and support for the various problems that people have (Baskerville, 2009), added to some beliefs related to masculinity, the status in a group and the management of power have led to the population as a whole to naturalize violent responses to multiple stressors (Nascimento, Gomes, & Rebello, 2009).

Even though in Colombia agreements related to what has been called “the post-conflict,” have been implemented in this country an average of 18 victims are recorded every hour with multiple injuries, caused mostly in public roads (Instituto Nacional de Medicina Legal y Ciencias Forenses [INMLCF], 2018). Likewise, it should be considered that situations of violence frequently occur in homes, educational institutions, and neighborhood environments that are not documented due to their cultural legitimization (Lee, Becker, & Ousey, 2014).

The vast majority of these records are due to interpersonal violence defined as the deliberated use of human force related to the level of self-perceived thread characterized by the use of such force against oneself, other person, group of people, or community, with a high probability to cause injuries, death, psychological damages, developmental disorders, or deprivations (Krug, Dahlberg, Mercy, Zwi, & Lozano, 2003), which is presented to the extent that the subjects value a situation as stressful and are probably inclined by a hostile attitude to deal with it (Suldo, Shaunnessy, & Hardesty, 2008), or by an aggressive reactive or proactive response when experiencing or witnessing stressful situations (Brown, Fite, DiPierro, & Bortolato, 2017); leading to the performance of aggressive behaviors associated with violent behavior models with which subjects are identified (Potocnjak, Berger, & Tomicic, 2011), the lack of impulse control (Thompson & Auslander, 2011), the social support received in the moment of confrontation, and a pessimistic feeling in which other resolution alternatives (Seiffge-Krenke, Aunola, & Nurmi, 2009).

In addition, violent behavior can effectively contribute in certain social contexts to dissuade a stressful situation, and therefore, give the aggressor a feeling of well-being and satisfaction (Gómez-Acosta & Londoño-Pérez, 2013). Likewise, when people live in highly unstable or stressful family nuclei, a greater impact can be expected from the effects of the mistreatment received on their physical and mental health (Topitzes, Mersky, Dezen, & Reynolds, 2013) as well as a greater predisposition to react violently (Mendelson, Turner, & Tandon, 2010).

Although there are studies that link psychological factors associated both with the explanation of interpersonal violence (Botelho & Gonçalvez, 2016), the vast majority continue to focus on the identification of risk factors such as poverty, exclusion, and marginality (Pridemore, 2008), in factors related to psychopathy’s (American Psychiatric Association, 2013), or in elements associated with biological predisposition (Raine, 2013), and so they are attributed the role of causal agents of violence. On the other hand, research has focused more on identifying stress, understood as a particular kind of individual-environmental relationship, where the subject evaluates the stressful situations as “overflowing” in relation to the perception of his own coping abilities (Campo-Arias, Bustos-Leyton, & Romero-Chaparro, 2009), seen as a consequence of violent acts, than stress and inadequate coping defined as the less effective process used by people in order to manage specific stressful situations (Londoño et al., 2006), as a possible trigger for violent behavior.

In response to the previous considerations, it is proposed to investigate to what extent the family conflict and the presence of stress and inadequate coping strategies predict the occurrence of violent behavior.

Method

Design of the study

Empirical-analytical cross-sectional descriptive-correlational research, with multivariate analysis.

Subjects

Through a snowball sampling, 291 persons (68% women) from the middle socioeconomic strata from Bogotá City were obtained. The inclusions criteria required that all participants should be legal adults (age over 18) at the moment of the application test, with literacy skills. All of them had signed the informed consent. It was a heterogeneous sample in relation to some inclusion criteria like academic formation, occupation, or religious beliefs. As for exclusion criteria, those who declined to continue in the middle of the research test application process were excluded.

Measurements

All of the measures used for this research were self-reported tests. It started with a survey of sociodemographic characteristics and continued with the assessment of factors associated with the interpersonal violence. An ad hoc structured record was designed by the authors (with content validation developed by three experts), which collects information about age, sex, family conformation and information about the occurrence of interpersonal violence inflicted by family.

Aggression Questionnaire (Adaptation for Colombia by Chahin-Pinzón, Lorenzo-Seva, & Vigil-Colet, 2012). It consists of 29 items that evaluate the instrumental dimensions of aggression (physical and verbal), as well as the cognitive component (hostility) and anger (Alpha = .83).

Perceived Stress Scale (PSS-14). Adapted for Colombia by Campo-Arias et al. (2009) to review its psychometric properties. It is configured by 14 items that measure the degree to which life situations are weighted as unpredictable and uncontrollable overloads (Alpha = .86).

Modified Coping Strategies Scale (MCS-S) - Adapted for the Colombian context by Londoño, (2006), it consists of 69 questions that inquire about 12 typical coping strategies used by people faced with different stressing challenges: problem solving, seeking social support, waiting, religion, emotional avoidance, seeking professional support, aggressive reaction, cognitive avoidance, positive reappraisal, expression of the difficulty in coping, denial, and autonomy (Alpha = .84).

Procedures

Participants were workers that came from general labor, health labor, and superior educational labor sector who were invited to participate voluntarily, and subsequently signed an informed consent form. Once they accepted to participate, they were conducted to empty and isolated places, separated to the presence of any possible distractors. After, they completed the psychometric test about the sociodemographic and psychosocial variables described. The information was systematized using the SPSS 24 software and the AMOS application.

Statistical analysis

We applied the descriptive statistics provided for sociodemographic characteristics perceptions of interpersonal violence factors. To determine if parametric or non-parametric statistics should be used, we previously used the Kolmogorov–Smirnov statistic test, which indicated that all of the subscales had a parametric distribution. Furthermore, as adjustment parameters for the acceptance of the SEM, a p-value less than or equal to .05 has been indicated (Hair, Black, Babin, & Anderson, 2010), a comparative index of Tucker-Lewis (TLI) greater than or equal to .95, a ratio of chi-squared/degrees of freedom between 2 and 3, a root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) greater than .05, and a normalized factor impact (NFI) greater than .90 (Escobedo, Hernández, Estebané, & Martínez, 2016).

Ethical considerations

The institutional ethics committee approved the proposal and the procedures of this study. The participants had the opportunity to learn about the study and participate according to the ethical considerations for research with humans in force in Colombia.

Results

Regarding the personal assessment of the relationships with their relatives, and the given relationships among their relatives, between 16.8-21.6% of the sample rated these items with six points or less, on a zero to ten scale. More than 40% of the participants of the sample described having at least one violent participant in their family, and the participants reported that in their families there were important percentages in the types of violent behavior like extramarital problems, insults, yelling, indifference, and negligence (Table 1).

A significant percentage of people related that in their family there was at least one participant who behaved in a violent manner in their daily lives, an aspect that may be associated with the fact of social legitimacy that has been given to violence as an appropriate way to solve conflicts (Nascimento et al., 2009; Lee et al., 2014).

On the other hand, the sample was heterogeneous in terms of the scores obtained in the dimensions that make up the violence questionnaire, so there were extreme scores. These scores indicated that the sample there were people without any reference of aggressive reactions, but there were also others that showed high levels to be classified as aggressive ones. Also, there were people from the sample with extremely high and extremely low levels of stress. An analogous situation is documented for the stress scale. Likewise, it was found that the most recurrent coping strategies are based on problem solving, social support, emotional avoidance, cognitive avoidance, positive reappraisal and autonomy, while the least used are waiting, religion, professional support, and aggressive reaction (Table 2).

Additionally, the level of aggressiveness was grouped or classified into three different levels (high, medium, and low) considering as a criterion the standard deviation, and according to this an analysis of variance (ANOVA) was applied, determining differences in the averages of the evaluations to the violence expressions among the family, family conflict, total stress, waiting, emotional avoidance, cognitive reappraisal, and expression of coping difficulties (Table 3).

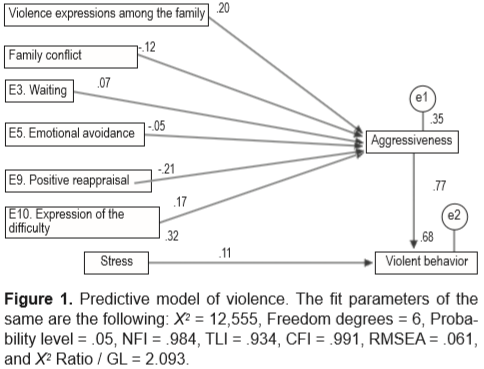

According to the mean differences, it was decided to perform the SEM procedure with the total scores obtained from every single implemented measure, running 24 different SEM possibilities, and reporting the one that explained the greatest amount of variance possible in the occurrence of violence (Figure 1).

According to the exposed model, the variables “average of expressions of intrafamily violence”, “family conflict”, “stress” and coping strategies “waiting”, “emotional avoidance”, “lack of positive reappraisal”, and “difficulty expressions” explain the variance of violence by 68%; the adjustment indicators (p = .05, NFI > .95, CFI > .95, RMSEA < .08, and ratio of chi square/degrees of freedom it is between 2.0 - 3.0) are optimal, except for the TLI index which was a little bit under the required score (.934), but could be considered as a well-adjusted level based on the degrees of freedom, without overparameterization of the model.

Discussion and conclusion

A significant percentage of people reported that in their family there was at least one participant who behaved in a violent manner, an aspect that may be associated with the fact of the social legitimacy that has been given to promote violence as an appropriate way to solve conflicts (Nascimento et al., 2009; Lee et al., 2014). Further, the sample was inclined towards coping strategies focused on the causes and consequences of the specific problem, requesting for close social support and appealing to autonomy when they consider it is necessary; however, when they feel that the demands of the environment overflow their own capabilities, they tend to emotionally and cognitively avoid the adverse event.

There are higher scores in the violence related to the increase of stress factors, the violence expressions among the family, and the waiting, emotional avoidance, aggressive reaction, and expression of the coping strategies; in that order, the use of strategies who result to be usefulness for the subject to stressful conditions is not effective, and also predisposes the violent reaction (Faasse & Petrie, 2015). On the other hand, the violence averages diminish when the use of coping strategies aimed at the positive reappraisal increase. It could be stated that this population prefers to eliminate the thoughts that are considered negative in relation to the challenging situations.

The adjusted goodness-of-fit parameters of the model support the working hypothesis in which family factors, stress, and undesirable forms of coping explain the violent behavior of the population approached. In effect, situations of conflict and express manifestations of physical or emotional violence of any kind in the environment in which people have grown and developed (Jung, Herrenkohl, Lee, Klika, & Skinner, 2015), including the family scenario and as a couple (Price, Bell, & Lilly, 2014), added to other stressful situations in the here and now for people can trigger, if adequate coping resources are not present, negative attitudes and beliefs accompanied by the intention to inflict harm towards the people or things that are immersed in these contexts (Botelho & Gonçalves, 2016); if these attitudes are not effectively overcome, it is possible that the presence of a new stressful event facilitates the appearance of physiological and behavioral responses to violence itself, which is consistent with the proposal of Palmero, Gómez, Guerrero, Carpi, Diez, and Diago (2007).

The incorporation of strategies such as waiting and the expression of difficulty in coping perhaps indicate situations in which the subject does not have sufficient skills to overcome critical situations, and ends in turn generating hostile feelings, and additionally, it is illustrated as factors as a well-managed emotional avoidance linked with a positive reappraisal of the different events can contribute to the reduction of hostility, and in this way, to a lesser expression of violent behavior.

However, it must be borne in mind that the factors involved in the model are not universal, because by definition they are ambiguous and very relative both to the relationship established between the subjects and the situations where they interact (Ward & Fortune, 2016) and to the symbolic load that said violence represents in the cultural environment where it is developed (Lee, 2016). Likewise, these outcomes must be made with caution, considering that reference is made to not necessarily usual strategies of coping in the people of the sample.

On the other hand, although ethical precepts are applied to ensure the confidentiality and anonymity of people, in self-report tests such as those applied, it is possible that some answers are biased due to the assumption of social desirability and because they appeal to memories and experiences that occasionally are inaccurate, so it is pertinent to contrast the model with information that is less subject to manipulation.

It is suggested that future research based on what has been discussed up to this point inquiries about the configuration of personal protective characteristics (static as personality or intelligence, and dynamic such as self-control, interpersonal relationships, and coping strategies) as well as of their reciprocal interaction with family, environmental, and situational factors (Ward & Fortune, 2016) to reduce the risk of interpersonal violence.

Also, it is recommended that clinical intervention models should have protocols that allow addressing the predictive factors investigated, including the participation of the family or the reference group, to reduce risk factors of violent behavior, emphasizing the formation of adaptive coping resources (Gagné & Melancon, 2013), following techniques of cognitive restructuring, relaxation, positive reappraisal and problem solving, strengthening of social skills, flexibility in emotional regulation and increase in moral reasoning, among others, that are considered ethical, relevant and cost-effective (Fortune & Ward, 2017), and its real effect on the reduction of such forms of behavior (Klepfisz, Daffern, & Day, 2017).

To conclude, the SEM developed in this study allow to demonstrate some variables that can be predictors of interpersonal violence, but it is necessary to carry out new investigations, particularly longitudinal ones, to consolidate the explanatory potential exposed and that account for both the acquisition and maintenance of prosocial beliefs and practices, as well as the evolution of the different associated psychosocial factors.