Introduction

Parenting styles play a fundamental role in the mental health of children because with them, parents set limits and rules as well as an affective exchange with their children. Previous studies documented the significant interactive effects between severe discipline on the part of parents and such problems in children (Chen et al., 2015; Hser et al., 2015; Leathers, Spielfogel, Geiger, Barnett, & Voort, 2019; McCullough & Shaffer, 2014; Porche, Costello, & Rosen-Reynoso, 2016). Furthermore, Pearl, French, Dumas, Moreland, and Prinz (2014) concluded that paternal quality predicts child externalization, and they suggest continuing with research that accounts for the implications of parenting on children’s adjustment.

Other psychological problems that affect the adaptation of children are internalizing behaviors. Voltas, Hernández-Martínez, Arija, and Canals (2016) report that children with depression and anxiety show a higher deterioration in their activities at home, school, and in their relationships with their peers.

In Colombia the range of highest prevalence of clinical problems is 8 to 12 years, with the presence of at least one symptom of internalizing and externalizing type being reported in 44.7% of the cases. It is a figure close to half the total child population, which makes it a public health problem and merits studying parental variables associated with the development of these problems in children in this age range (Ministerio de Salud & Colciencias, 2015).

As for the role of cohesion and family communication, Jouriles, Rosenfield, McDonald, and Mueller (2014), as well as Zuñeda, Llamazares, Marañón, and Vázquez (2016), found that when there are problems in family dynamics, there is a lower capacity to adjust to vital family events, as well as aggressive behavior in children. As for shared leisure, Baker (2014) found associations with school adjustment in children, and Offer (2014) did the same with higher positive affect on children. In the opposite sense, externalizing problems in children were associated with a diminished dedication of the mothers to their children (Chisholm, Gonzalez, & Atkinson, 2014) and with low satisfaction and commitment of the raising by both parents (Raya, Pino, & Herruzo, 2009).

On support relationships between family and school, Barg (2019) and García-Bacete (2003) emphasize that parents who value their role in the education of their children improve communication with them. In relation to parental overload, lack of parental support hinders the development of pro-social skills and emotional regulation in children (Murry, McNair, Myers, Chen, & Brody, 2014).

On the other hand, difficulties to resist and/or control impulses hinder the processes necessary for the emotional regulation and for adjustment to the environment. In this sense, impulsivity has been linked to diminished self-control (Hamilton, Sinha, & Potenza, 2014), and provides a risk of maltreatment of children (Henschel, de Bruin, & Möhler, 2014).

The emotional expression of parents in the family ambit is important because it is the primary context in which children gain an understanding of the emotions of others (Bariola, Gullone, & Hughes, 2011). Parents who are less accepting of their children’s emotions generate adjustment problems for them (Cumsille, Martínez, Rodríguez, & Darling, 2015; Mirabile, 2014; Ramírez-GarcíaLuna, Araiza-Alba, Martínez-Aguiñaga, Rojas-Calderón, & Pérez-Betancourt, 2016).

In different studies it has been reported that the use of a democratic upbringing style has positive emotional and behavioral effects on children (Osorio & González-Cámara, 2016; Rankin Williams et al., 2009; Uji, Sakamoto, Adachi, & Kitamura, 2014). Also, said educational style is a safe-conduct for the education and development of socially accepted behaviors (Jabagchourian, Sorkhabi, Quach, & Strage, 2014).

Otherwise, the educational permissive style has been associated with internalizing problems in children (Rankin Williams et al., 2009), with difficulties in their school adjustment process (Moreno, Echavarría, Pardo, & Quiñones, 2014), and impairments in children´s mental health (Barton & Hirsch, 2016; Uji et al., 2014).

Regarding the ambiguous/non-consistent style, Hernández, Gómez, Martin, and González (2008) found that frequent punishment or allowing children to perform activities that are normally prohibited are risk factors for behavioral problems (Jiménez-Barbero, Ruiz-Hernández, Velandrino-Nicolás, & Llor-Zaragoza, 2016).

The educational authoritarian style is related to externalizing and internalizing problems in children (Leiner et al., 2015; Rescorla, Althoff, Ivanova, & Achenbach, 2019; Stoltz et al., 2013) and poor affiliation with parental values (Barry, Frick, & Grafeman, 2008). Laukkanen, Ojansuu, Tolvanen, Alatupa, and Aunola (2014) found that the mother’s feelings of inadequacy may lead her to use psychological control with the child, typical of an authoritarian style. Such a style worsens the mental health of children and their psychological well-being (Scharf, Mayseless, & Rousseau, 2016; Uji et al., 2014).

Iglesias and Romero Triñanes (2009) emphasize that the maternal negligent style and paternal authoritarian style have both low scores on the acceptance/implication factor and an association with externalizing behavior in common (Rankin Williams et al., 2009). Respect for parental authority is of paramount importance to families, this fundamental value was defined by Livas-Dlott et al. (2010) as affiliative obedience. Stein and Polo (2014) found that when there is greater discrepancy in affiliative obedience, children are more likely to report more depressive and maladjustment symptoms. Based on all of the above, the aim of this study was to increase the knowledge about the role of which parental educational styles are associated with externalizing, internalizing, and adjustment problems in Colombian children.

Method

Study design

Cross-sectional in paper-based survey.

Participants

The sample was selected under a probabilistic procedure using simple random sampling with a confidence level of 95%. The inclusion criteria were: 1. parents over 18 year of age, 2. parents with a minimum educational level of five of primary school, 3. children between 8 and 12 years old, 4. parental informed consent, and 5. informed assent of children.

The exclusion and modification criteria were: 1. parents under 18 years of age, 2. parents with an educational level below five of primary school, 3. children under 8 years and over 12 years, 4. lack of informed consent of parents, and 5. lack of informed consent or assent from parents and children.

The elimination criteria were: 1. incomplete instruments answered and 2. voluntary withdrawal of parents or children.

Instruments

Parent Educational Styles Assessment Questionnaire (PESQ). It allows for the evaluation of parental styles that can be constituted as factors of protection or risk or in the development of psychological problems in children between 6 and 12 years old. The questionnaire is made up of 66 Likert-type items with four response options (1 most often, 2 frequently, 3 sometimes, 4 rarely). It has five scales with corresponding factors that are: Parental practices (promote positive behaviors, dysfunctional reactions to disobedience, inconsistency, proper use of corrections); Educational styles (democratic, permissive, ambiguous, authoritarian); Emotional competences (impulsiveness, emotional expression, recognition of emotions, emotional management); Parental role (parental satisfaction, collaboration with school, parental overload), and Family dynamics (family cohesion, communication, shared leisure, conflicts). The instrument reliability is .92. Its scales have mean and high reliability scores of .64 and .84 (Gómez et al., 2013).

Child Behavior Checklist (CBCL; Achenbach & Rescorla, 2001), parent format: allows for evaluating internalizing and externalizing psychological problems in children between 4 and 16 years old. It has a rating as follows: (0) if it is not true, (1) if sometimes it is true and (2) if it is true very often. The direct scores are transformed into T scores according to the following ranges: clinical: between 64 and 100, borderline: between 60 and 63, normal: between 59 and 33 (Achenbach & Rescorla, 2001). This instrument has been adapted for the Colombian population where it obtained a reliability coefficient of .83 and an internal consistency of .94 (Hewitt, Jaimes, Vera, & Villa, 2012).

Self-Assessment Multifactorial Adjustment Test for Children (TAMAI; Hernández-Hernández, 2004). Allows for self-evaluation of personal, social, school, and family non-adjustment scales, in children from 8 to 18 years of age. It has a reliability index = .87. It has the following ordinal categories: (very low, 1 to 5 centile); (low; centile of 6 to 20); (almost low, centile 21 to 40), (medium, centile 41 to 60); (almost high, 61 to 80); (high, centile 81 to 95); (very high, centile 96 to 99).

Procedure

First, requests to perform the study were sent to the two schools. 750 parents were invited to participate in the study; for this purpose, each school called the parents to a meeting in their facilities. Finally, 422 participated in the study, corresponding to 56.3%. Some did not attend the meetings where the study was presented and others were removed because they did not fully complete the instruments. The parents gave their informed consent to complete the instruments at school, just after explaining the study. To avoid overloading parents with time to complete the instruments, it was verified that they were only answered once based on one of the children included in the study. Subsequently, the objectives of the study were explained to the children and their informed consent was requested to complete the questionnaires in the classroom.

Statistical analysis

A path analysis was carried out using the AMOS 22 software in which, through structural equations, the fit of the proposed model was verified. We examined whether the hypothetical relationship patterns were consistent with the observed covariance matrix. The fit indexes were those recommended by Hu and Bentler (1988) for varied samples and different distributions: square chi (χ2, cut point p > .05), goodness index adjustment (AGFI; The comparison adjustment index (CFI > .95), and the mean squaring error of approximation (RMSEA < .06). Finally, revisions of the change indexes were carried out to determine the best adjusted empirical model.

Ethical Considerations

The Ethics Committee of the Universidad of Miguel Hernández de Elche approved the study (53245409-H). In order to be granted access to the participants, school principals were asked to provide authorization beforehand. Study objectives were then explained to parents with the purpose of obtaining a signed informed consent to complete the instruments. These steps were taken in accordance to the Helsinki Declaration. Also, the confidentiality on the identity of the participants was provided to comply with ethical considerations.

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Results

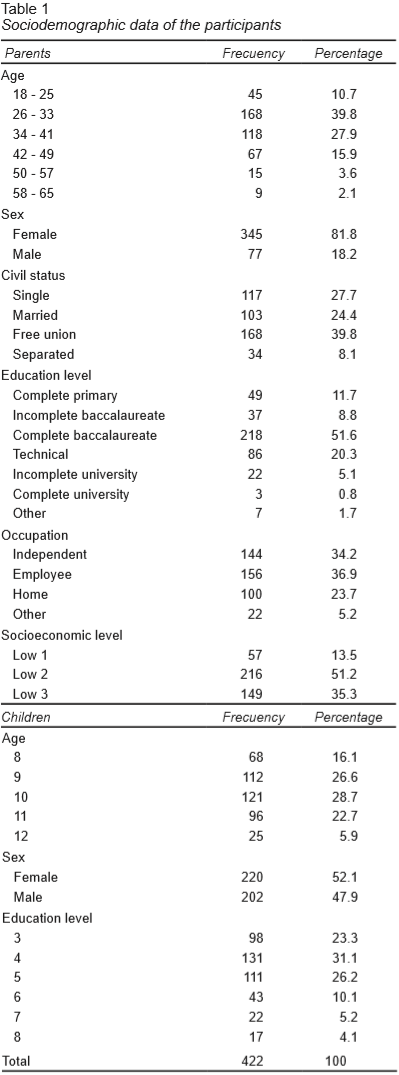

The participants were 422 parents and 422 children (52.1% girls) with an age range from 8 to 12 years (M = 9.71; SD = 1.2), of which 31.1% were in fourth grade in public schools in the city of Bogotá. 81.8% were mothers and 18.2% were parents. 39.8% were in free union, 27.7% were single, and 24.4% were married. 29.6% of the parents were employed; while only 7.3% of the mothers were employed (Table 1).

In Table 2 it can be observed that in the PESQ the parents reported greater use of communication (M = 9.42) and the promotion of positive behaviors (M = 9.35) in parenting. They also reported more aggressive behavior in their children (M = 7.32), while in children more problems of personal adjustment were found (M = 9.37).

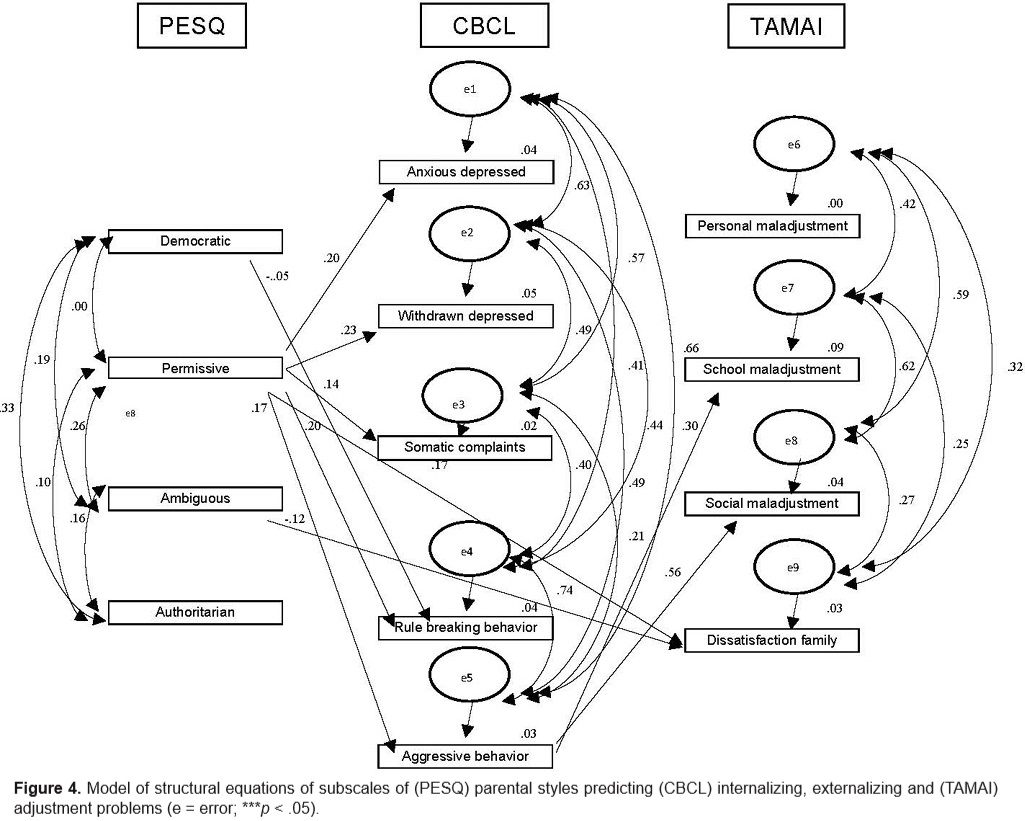

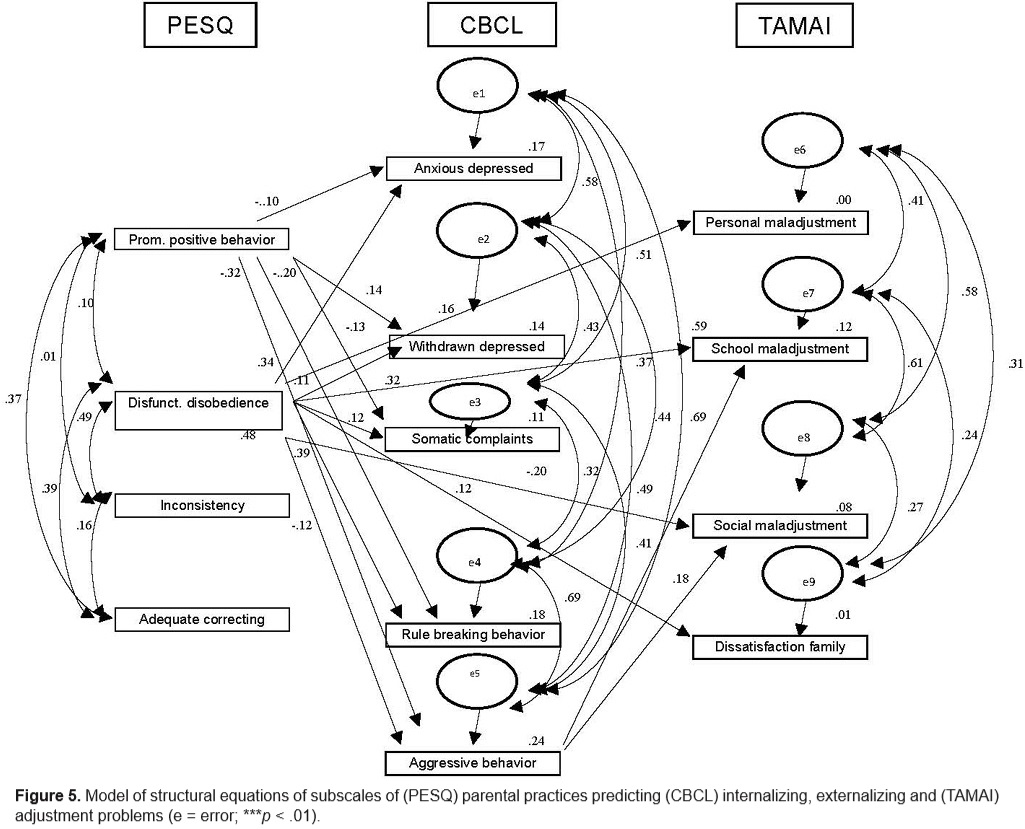

As shown in Table 3, the adjustment indicators were favorable for the five established models, since the comparative adjustment index (CFI), goodness of fit index (GFI), adjusted goodness of fit index (AGFI) and the normalized adjustment index (NFI) were above .90 indicating a good fit, and the root of the average squared error of approximation (RMSEA) was below .08.

According to Figure 1, family cohesion, communication, shared leisure, and parental conflicts have a direct effect on anxious-depressive behavior in children. Communication and conflict show a direct relation to the isolated-depressive variable. Communication has a direct effect on the rule breaking behavior. There is an indirect effect of communication problems and family conflicts through aggressive behavior on school and social maladjustment of children.

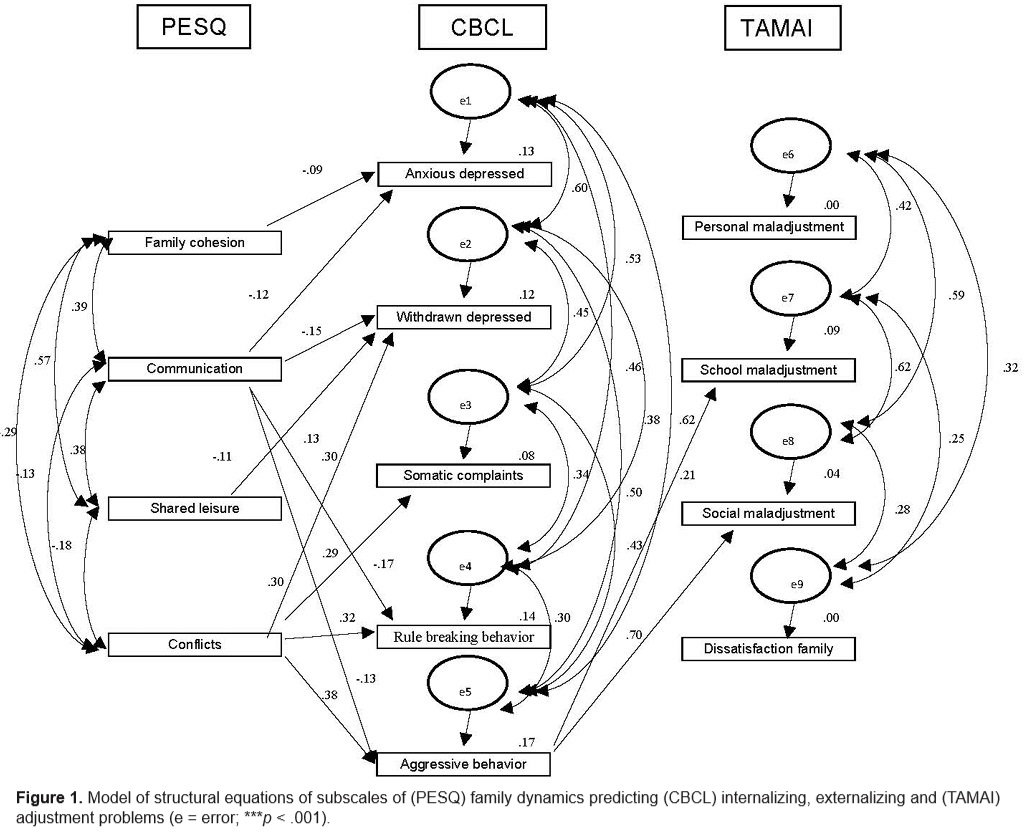

According to Figure 2 , parental overload shows direct effects on anxious-depressive, isolated-depressive, somatic complaints, rule breaking, and family dissatisfaction. In turn, it shows indirect effects on school and social maladjustment through aggressive behavior. Parental satisfaction directly influences the breaking of rules and indirectly on school and social maladjustment through aggressive behavior. Parent collaboration with the school has a direct influence on school maladjustment of their children.

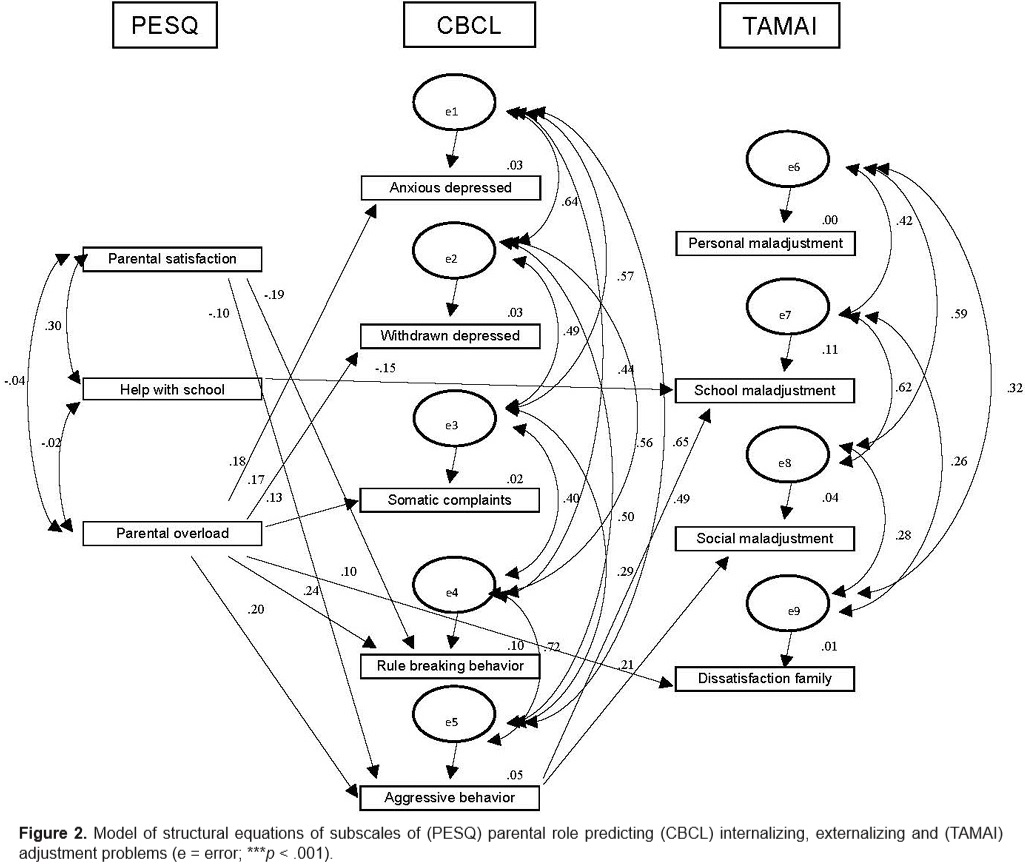

In Figure 3, impulsiveness has direct influences on anxious-depressive, isolated-depressive, somatic complaints, rule breaking, aggressive behavior, school, and social maladjustment. Emotional expression directly explains the isolated depressive problem and the breaking of rules, and indirectly influences school and social maladjustment through aggressive behavior. Emotional recognition and handling co-vary with impulsiveness and emotional expression without direct effect on internalizing, externalizing, and adjustment problems.

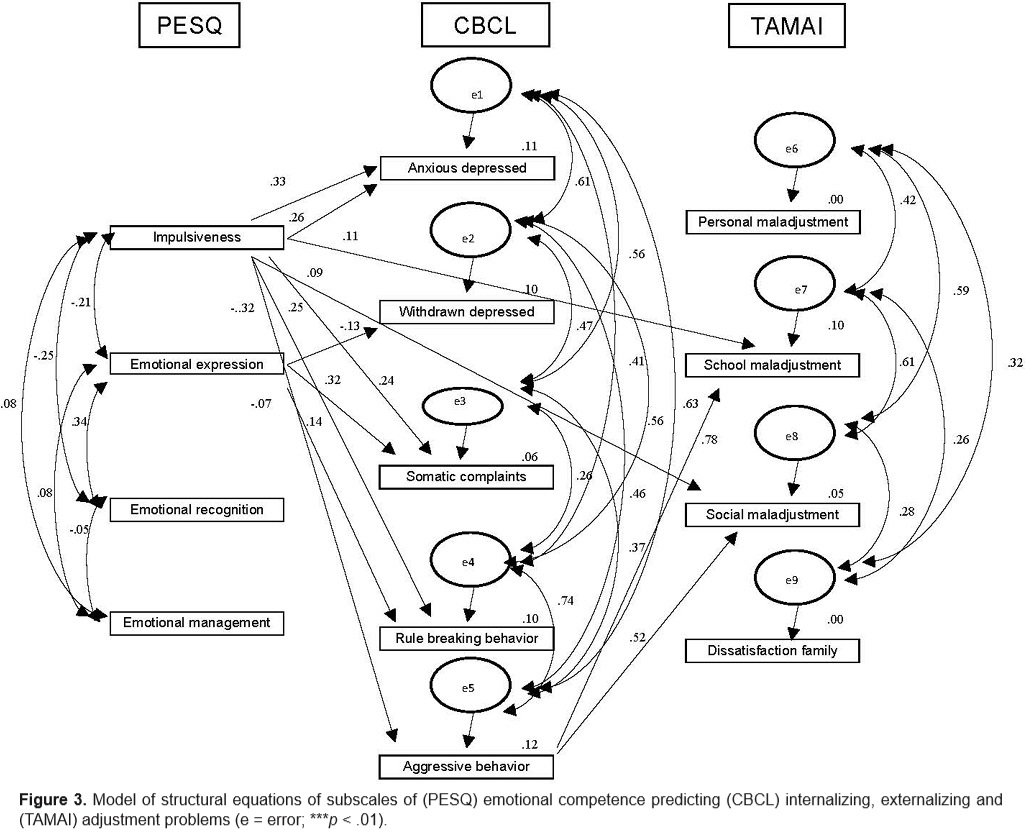

According to Figure 4, the democratic parental style directly influences rule-breaking, while the permissive style has direct influences on anxious-depressive, isolated-depressive, somatic complaints, rule breaking, and family dissatisfaction; On the other hand, it also shows indirect influences on school and social maladjustment through aggressive behavior. Ambiguous style denotes a direct influence on family dissatisfaction. Recognition and emotional management co-varied with impulsiveness and emotional expression without direct effects on internalizing, externalizing, and adjustment problems.

As shown in Figure 5, promoting positive behaviors explains directly the anxious-depressive, isolated-depressive, and somatic complaints. It also has indirect influences on school and social maladjustment through rule breaking and aggressive behavior. The dysfunctional reaction of parents to the disobedience of their children evidences a direct influence on the anxious-depressive, isolated-depressive, and somatic complaints, rule breaking and aggressive behavior, as well as on personal, school, and social maladjustment, and family dissatisfaction. The correct use of corrections covariate with the promotion of positive behaviors, dysfunctional reaction to disobedience and inconsistency without direct effects on internalizing, externalizing and adjustment problems.

Discussion and conclusion

The present study allowed to increase the knowledge about the role of which parental educational styles are associated with internalizing, externalizing, and adjustment problems in Colombian children. Five tested models show that conflicts at home, parental overload, impulsivity, permissive, ambiguous/non-consistent styles, and dysfunctional reaction to disobedience play a role in the manifestation of internalizing, externalizing, and adjustment problems in children. Contrary to the above, family cohesion, communication, shared leisure, parental satisfaction, collaboration with school, recognition, emotional management, and expression, democratic style, and the promotion of positive behaviors emerge as protective factors for psychological and adjustment problems.

The results found that difficulties in family cohesion, communication, shared leisure, and conflict play an important role in internalizing problems. This is in line with the findings of Cumsille et al. (2015) who state that, when children perceive little affection and insecurity, they show anxiety and depression. In turn, Verdugo et al. (2014) report that, the greater the family cohesion, is the better adjustment in the children is. Baker (2014) and Offer (2014) emphasize that for children it is beneficial for their school adjustment to have shared time with their parents because they experience high positive affection, something fundamental for positive parenting.

It is striking that most children live in non-traditional homes characterized by parents who have a free union and single-parent homes. This could have an impact on the upbringing of the children, since the parents would have fewer opportunities for dedication of the children and as a consequence the manifestation of adaptation problems in the children (Chisholm et al., 2014; Muratori et al., 2016).

Communication and conflict also have a link with externalizing problems and school and social maladjustment. Jouriles et al. (2014) and Zuñeda et al. (2016) found that children with communication problems in the family ended up having aggressiveness and difficulties in adapting to life events.

Parental overload also shows effects on internalizing and externalizing problems and on school and social maladjustment, since the lack of parental involvement and support in child nurturing makes it difficult to develop prosocial skills and self-regulation in children, which in turn leads them to show problems of sub-controlled or hyper-controlled behavior and difficulties to respond to the demands of school and social environment (Chisholm et al., 2014; Murry et al. 2014; Muratori et al., 2016; Raya et al., 2009).

On the other hand, the role of parental satisfaction and collaboration with school on behavioral problems and school maladjustment can explain why, when parents feel satisfied with their children’s education, they are more willing to set limits and consistent standards, which allows children to respect and follow the family rules (Barg, 2019; García-Bacete, 2003).

Regarding the role of parents’ impulsivity about externalizing behaviors, Hamilton et al. (2014) and Henschel et al. (2014) report that impulsivity is related to decreased self-control and increased aggression in children. The direct relationship of emotional expression to internalizing problems problems would indicate that the frecuency and valence of positive verbal and nonverbal emoticional expressions of parents towards their children is low can be explained according to what (Bariola et al., 2011), when parents have cold attitudes and disregard their children’s emotions, they hinder their emotional development and socialization processes (Mirabile, 2014; Ramírez-GarcíaLuna et al., 2016).

The democratic or authoritative style directly influences the behavior of breaking rules. This is consistent with what has been found by Jabagchourian et al. (2014), Jiménez-Barbero et al. (2016); Rankin Williams et al. (2009), in the sense that this style is associated with a decrease in externalizing behaviors and follows up of rules, since when parents are affectively warm, they use reasoning and promote autonomy, they can strengthen emotional security and the manifestation of adjustment behavior in their children. It also has a beneficial impact on children’s mental health and education (Osorio & González-Cámara, 2016; Uji et al., 2014) and the development of socially accepted behaviors.

A permissive parental style has direct influences on internalizing problems. It has been associated with such problems, especially in children who have behavioral inhibition patterns (Rankin Williams et al., 2009). It also shows indirect effects on school and social maladjustment through aggressive behavior. This is consistent with the findings of Moreno et al. (2014) and Babinski, Waschbusch, King, Joyce, and Andrade (2017) because the permissive style affects the adjustment and the school performance of children. It also has an impact on their mental health (Barton & Hirsch, 2016; Uji et al., 2014).

An ambiguous/inconsistent style denotes a direct influence on family dissatisfaction. This may be because ambiguity generates confusion and uncertainty and frustration in children. On the other hand, consistency in parenting favors the development of high levels of self-control and family satisfaction (Berkien, Louwerse, Verhulst, & Van der Ende, 2012). Iglesias and Romero Triñanes (2009) found that the permissive parenting style of mothers combined with the authoritarian parenting style were associated with externalizing child problems and depression. The common element is that they are ineffective styles, because the predominant use of any of these dimensions maintains an inconsistent raising style (Laukkanen et al., 2014).

The promotion of positive behaviors and the dysfunctional reaction to disobedience show an inverse relationship with the internalizing and externalizing problems with the consequent problems of school and social maladjustment and family dissatisfaction. According to Barry et al. (2008), positive parenting perceived in children has an inverse relationship with depression in them. Berkien et al. (2012) have found a relationship between negative parenting patterns and symptoms of anxiety and depression. These symptoms in turn interfere with school and social adjustment (Voltas et al., 2016).

The infrequent use of positive parenting practices may be associated with a lack of affiliation with parental values, and possibly with links to other aspects of the community, such as a child will be more likely to engage in activities (Barry et al., 2008) and to report higher levels of depressive symptoms and maladjustment (Stein & Polo, 2014).

The results of the present study have important implications for mental health, because they provide information based on the evidence of instruments such as PESQ, CBCL, and TAMAI that can be used in clinical evaluations to understand the relationships between parental styles and adaptation problems in children, even though it was a school based sample.

At the school and community level, the study suggests information to strengthen the schools parents programs, and prevention and promotion strategies that include communication skills, conflict resolution, emotional regulation, and general guidelines for parents. These aspects help to prevent the problems of adaptation of children in the family, school, and social environment.

Limitations of the present study are that it was carried out in school settings and no comparison was made with a clinical sample, nor was the evaluation of teachers, which is a gap to be filled for future research.

It can be said that most results were obtained from the evaluation done by the mothers rather than fathers, since in the Colombian context it is more difficult to observe it is more difficult to access the sample of the male parent, in this sense it is suggested for future investigations to include a homogeneous sample in this regard.

It was not possible to clearly identify the role of authoritarian parental style in externalizing, internalizing, and adjustment problems, which requires further deepening. Likewise, the results only allow for correlations and associations to be presented, which makes it impossible to establish causal relationships of the parents’ styles on the behavior of the children, so it would be necessary to conduct quasi-experimental and longitudinal studies that allow us to account for it.