INTRODUCTION

At the end of December 2019, in Wuhan (Hubei, China), a new illness (COVID-19) was discovered caused by the SARS-CoV-2 coronavirus (Zhu et al., 2020; Gorbalenya et al., 2020). The SARS-CoV-2 coronavirus rapidly spread internationally and was declared a global pandemic by the World Health Organization (WHO) on January 30, 2020 (WHO, 2020).

In Mexico, the first case of COVID-19 was identified on February 27, 2020, and the first death on March 18, 2020. Given the evolution of the disease, and the number of cases and deaths, on March 30, 2020, Mexico declared a “health emergency due to force majeure” (Suarez, Suarez-Quezada, Oros-Ruiz, & Ronquillo-De Jesús, 2020).

Faced with this critical situation, frontline healthcare workers that directly diagnose, treat, and care for patients with COVID-19 are exposed to numerous physical and mental stressors (Chen et al., 2020; Kang et al., 2020; Lai et al., 2020; Lancee, Maunder, Goldbloom, & Coauthors for the Impact of SARS Study, 2008; Shanafelt, Ripp, & Trockel, 2020). Consequently, they are at high risk for experiencing psychological distress and other mental health symptoms (Bohlken, Schömig, Lemke, Pumberger, & Riedel-Heller, 2020; Makino, Kanie, Nakajima, & Takebayashi, 2020). During COVID-19, healthcare workers have been found to have high rates of insomnia (38.9%), anxiety (23.2%), and depression (22.8%; Pappa et al., 2020).

Although medicine can be a highly rewarding profession, it can also be very stressful and demanding, having a potential negative effect on these professionals’ mental health. There is increasing evidence that shows a higher rise in the prevalence of common mental illnesses in doctors as compared to the general population, with distinct differences between sexes (Mihailescu & Neiterman, 2019; Tawfik et al., 2019; Zhang et al., 2020b).

Women physicians are often required to manage a double burden of balancing work with familial responsibilities (Juengst, Royston, Huang, & Wright, 2019; López-Atanes, Recio-Barbero, & Sáenz-Herrero, 2020; Staniscuaski et al., 2020; Wenham, Smith, Morgan, & Gender and COVID-19 Working Group, 2020; Zhang et al., 2020a). Thus, physicians who are also mothers, could be a group that is particularly vulnerable to developing psychological distress that impacts their quality of life (Chowdhry, 2020; Sandven-Thrane, 2020; Staniscuaski et al., 2020; Cluver et al., 2020), because they face additional challenges due to underlying structural inequalities based on gender. Their salaries are lower than those of their male counterparts (Ganguli et al., 2020), they often face discrimination or harassment in the workplace (Adesoye et al., 2017), not to mention that, socially, there is an expectation that, at home, they will take on a greater proportion of housework and childcare (Perry-Jenkins & Gerstel, 2020).

This research studied a group of Mexican physicians-mothers with the aim of: 1. characterizing their sociodemographic, academic, work and personal features, and the way in which these variables could be related to the presence of emotional symptoms, and 2. analyzing from a phenomenological perspective (Duque & Aristizábal Díaz-Granados, 2019), in a complementary manner, their experience as physicians and mothers facing the first stage of the COVID-19 pandemic. All this, seeking to elucidate the specific needs of this population and bring about reflections in the search for possible solutions. All this, seeking to elucidate the specific needs of this population and to raise reflections in the search for potential solutions.

METHOD

Design of the study

The present study used mixed research methods with a concurrent triangulation strategy design in a complementary mode with the aim of increasing the intelligibility, relevance, and validity of the concepts and the results of the applied survey.

Participants

Contestants invited were female physicians practicing medicine in Mexico, who also had children; which were considered inclusion criteria. Participation was voluntary and the sample, by convenience, was composed of all applicants who completed the online survey during the period that it was online.

Procedures and measurements

Information for this research was collected using an online survey that was developed to gather data on demographics, academic features, work information, mental health, concerns, and needs of doctor mothers during the first months of the COVID-19 pandemic.

The study instrument was an online anonymous survey delivered via Google Forms and distributed nationally through social media of network groups of physicians (Facebook, Instagram, WhatsApp) without previously knowing any of the participants. In Mexico, as in many other countries, there are groups of doctors and health personnel in all social media, so that the invitation to participate in this study, together with the link for the questionnaire, was distributed through these groups and, when it came to open pages, it was also published directly on the social media pages of health institutions (IMSS, ISSSTE, PEMEX, SEDENA, SSA, state health services, and private medicine). No personal invitations were sent. The invitation was posted daily during the period that this research lasted, and those doctor mothers women who were interested in being part of it, simply accessed the link to fill out the questionnaire.

After a review of the literature (Bohlken et al., 2020; Chen et al., 2020; Juengst et al., 2019; Kang et al., 2020; Lai et al., 2020; Lancee et al., 2008; López-Atanes et al., 2020; Makino et al., 2020; Pappa et al., 2020; Shanafelt et al., 2020; Staniscuaski et al., 2020; Wenham et al., 2020; Zhang et al., 2020a), and with the feedback of both psychiatrists and occupational physicians, as well as academic researchers in the fields of psychology, anthropology, and sociology, a 62-item questionnaire-based-survey was designed with both close- (57) and open-ended (5) questions which were organized in eight different sections: (a) Informed consent; (b) Sociodemographic data; (c) Children and family; (d) Medical profile, including whether they saw COVID-19 patients; (e) Health condition; (f) Changes in behavior since lockdown; (g) Worries and support needs; (h) Testimonies of the participants about their experience of the pandemic.

Given that Mexico celebrates “Mother’s Day” on May 10th, the survey was conducted during the month of May. The instrument was posted daily from the 4th to the 15th of May 2020 on social media. The tool contained an explanation of the research and instructions for completion of the survey.

To strengthen the validity and reliability of our research results, data triangulation (Martínez Miguélez, 2006) was performed during mental health care workshops that were offered to support the participants. At the end of each survey, there was an email to write to if you wanted to take a mental health care workshop. Of the 537 surveys answered, there were 468 people who sent an email requesting to participate in these workshops and finally 415 doctor mothers attended. They were 120-minute online sessions in which an overview of mental health was given and emotional management and mindfulness techniques were worked on. Regarding triangulation, in the introduction to the workshop, we shared with the attendees the preliminary global data of the study to verify the information obtained from them (as a group, not individually, so neither anonymity nor confidentiality was compromised at any time).

Analysis

The study was conducted using mixed methods.

Quantitative: Descriptive analysis (with frequencies, percentages, mean, and standard deviation depending on the variable). Two tailed t-tests and Pearson χ2 tests were conducted for comparisons. Generalized linear model with a robust method was carried out to evaluate the main characteristics of the participants with the increase in total symptoms. The findings were considered significant for p < .05. The statistical analysis was conducted with IBM® SPSS® Statistics (Version 24, IBM Corporation, New York, NY).

Qualitative: An interpretative analysis of the participants’ testimonies was completed using meaning categorization as proposed by Kvale (1996). Themes and subthemes were identified through reading the responses. Three researchers with wide experience in qualitative analysis coded the interviews individually (IVH, psychiatrist; SBG, psychologist; ACRM, psychologist). After individual coding, the categorizations were compared, and discrepancies were resolved through discussion and review of the original response. There was also an exploration of the content of the testimonies of the participants, which was carried out using the qualitative software NVivo® (Version 12, QSR International, Burlington, MA). This study is compliant with the Consolidated Criteria for Reporting Qualitative Studies (COREQ) framework (Tong, Sainsbur, & Craig, 2007).

Based on the study objectives, the analyzed categories were condensed into four large dimensions to report the results. This way, both qualitative as well as quantitative results are presented in four sections: a) Sociodemographic data, b) COVID and daily life, c) Presence of mental symptoms, d) Strength in the face of adversity.

Ethical Considerations

The research was approved by the Committees of Ethics and Research of Faculty of Medicine, Universidad Nacional Autónoma de Mexico (FM/DI/045/2020). The study was conducted in accordance with the ethical principles of online research (Markham & Buchanan, 2015). Informed consent was obtained from all participants and was included on the first page of the questionnaire, explaining the study objectives, characteristics, methodology, and information confidentiality. Psychological support was provided to the participants who requested it as well as to those with symptoms that indicated risk to the participant.

RESULTS

Sociodemographic

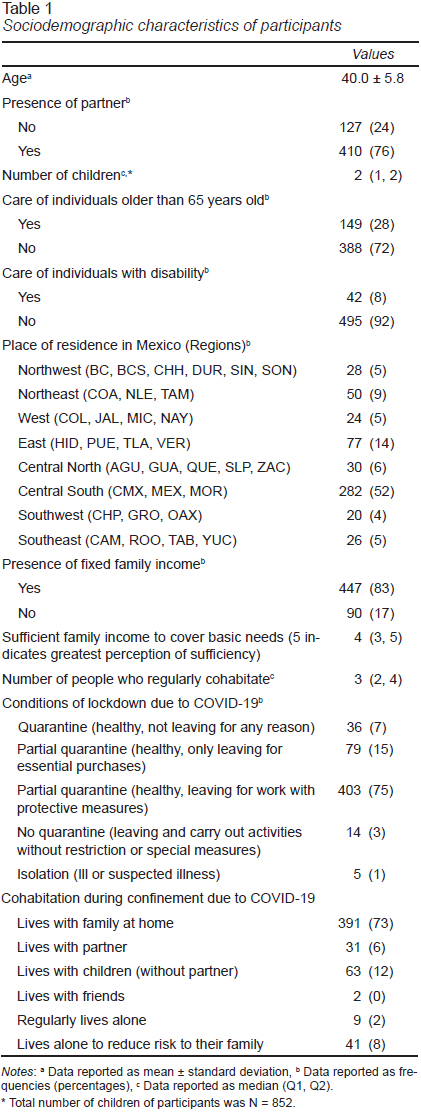

A total of 537 physician mothers participated in the study and had an average age of 40 years old. Most participants (76%) had a spouse or partner and had a stable family income (83%). They also had an average of two children. 75% percent were in partial quarantine and healthy. More than 70% indicated that they were living with their family (including partner) during this time, 12% lived only with their children, and 8% decided to distance themselves from their family to decrease risk of infection (Table 1).

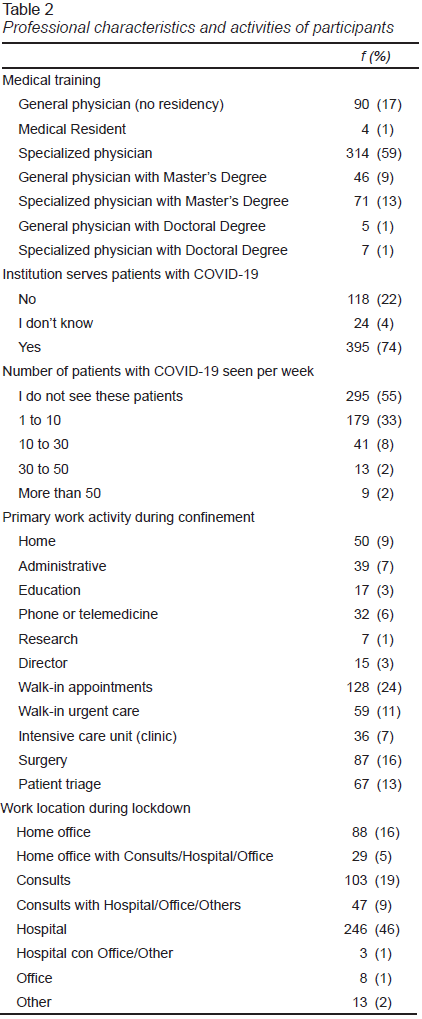

Regarding their professional life, more than half the participants had completed training in a medical specialty (59%). The majority (75%) worked in a hospital or a practice that sees patients with COVID-19; however, 55% of the participants do not see patients for issues related to the disease. The predominant type of work among these participants was walk in appointments (24%; Table 2).

COVID and daily life

This dimension included all the findings regarding the personal, family and professional lives of the participants during the first phase of the COVID-19 pandemic in Mexico. Family dynamics, changes in activities, experiences in the professional field, and the challenge of balancing work life and home and family care is the information included in this section.

This category of analysis is made up of the subcategories: Family, Practicing medicine, and Balancing multiple roles.

Family

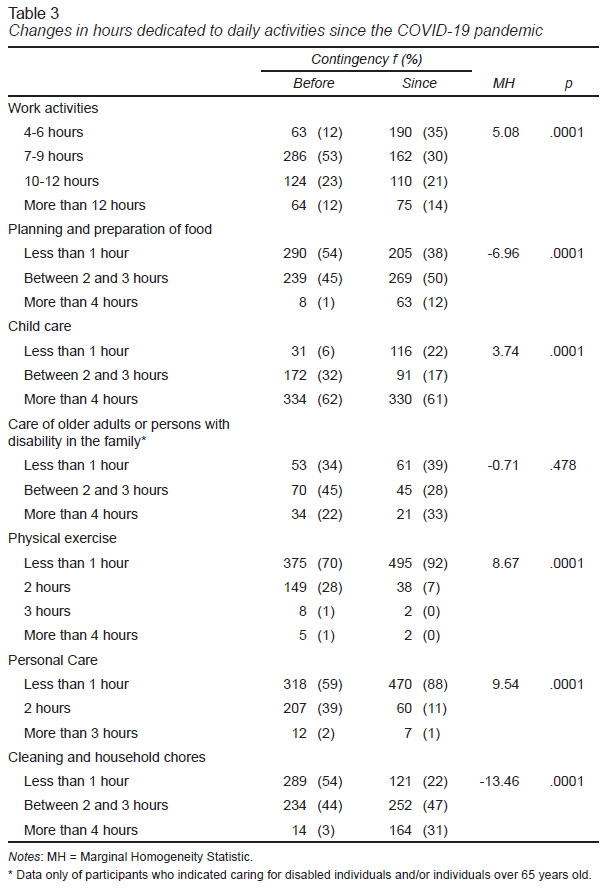

Given the conditions and restrictions of lockdown, the participants were required to restructure the amount of time dedicated to daily activities. They noticed a significant change in the distribution of time dedicated to these daily activities, with the exception of the care of older adults or persons with a disability, which remained the same. For example, the number of hours dedicated to work increased (MH = 5.08, p < .0001), as well as the time dedicated to childcare (MH = 3.74, p < .0001), and planning and preparation of meals (MH = -6.96, p < .0001). On the other hand, the number of hours dedicated to exercise (MH = 8.67, p < .0001) and personal care (MH = 9.54, p < .0001) decreased (Table 3).

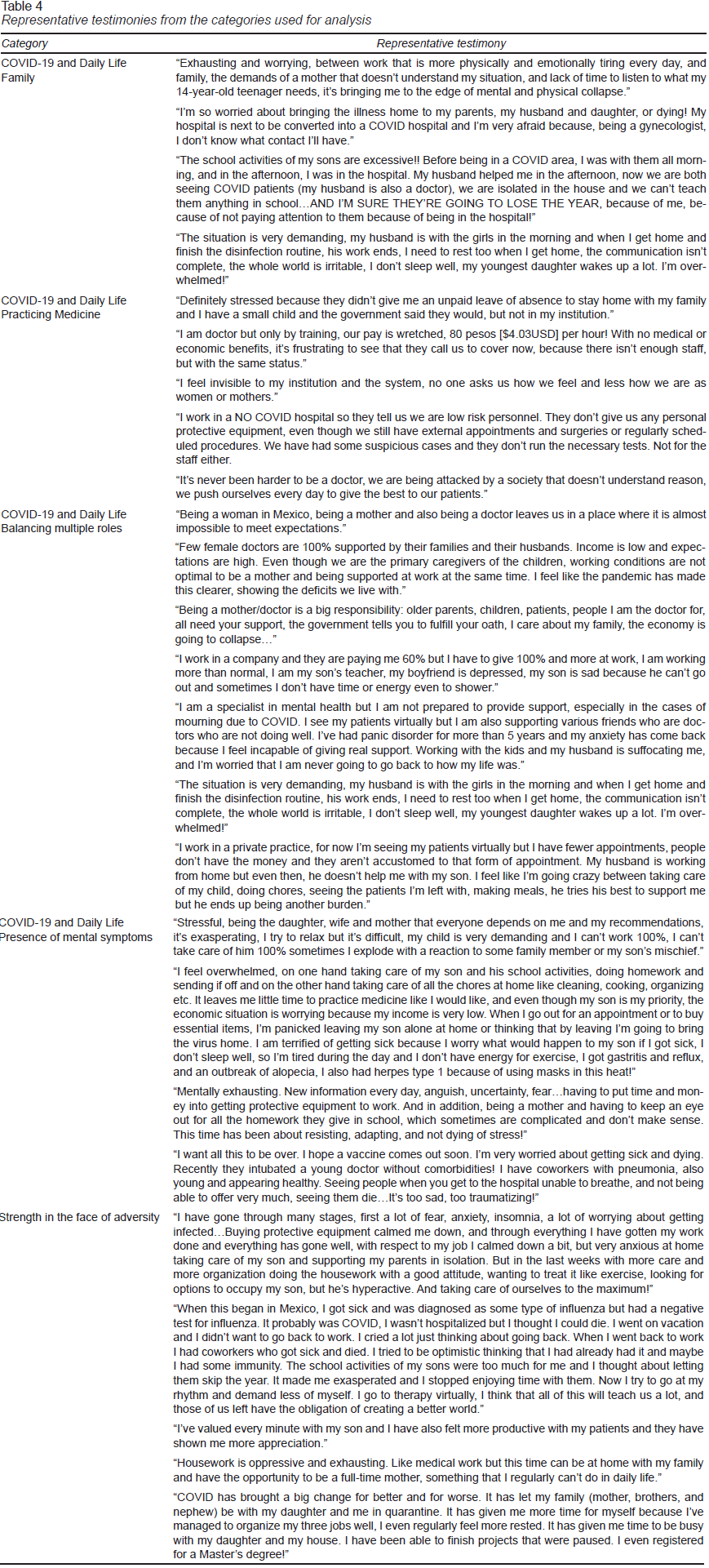

The narratives of the participants, at the last section of the instrument, provided an explanation of these changes in important areas such as family, (including childcare and interpersonal relationships), completing their work, and a need to fulfill multiple roles simultaneously.

With respect to family, the participants described the interruption that this pandemic had caused in their living conditions (Tables 3 and 4). Despite putting in great efforts to avoid competition for their time between their children, work, personal needs, they remained overwhelmed. They mentioned the lack of division between being a mother, wife, and full time professional as being “suffocating, concerning, complicated, stifling, frustrating.”

A set of participants (n = 12) reported having resigned from their job, asked for an unpaid leave of absence, or reduction in hours in order to devote more time to the care and education of their children. Decisions of the participants in these cases seemed to be related to the fact that school closings added additional pressure and additional demands such as ensuring that children were participating in school activities, attending virtual classes, and completing their homework, etc. In addition, some of these mothers cared for children with disabilities: “I am a cardiologist and I work in a private hospital, during the pandemic I stopped working so I could take care of my son who has autism.”

The narratives repeatedly mentioned fear, as well as anger, worry, and anxiety, with fear permeating almost every response. Some of this fear was related to bringing the virus home with them and infecting their family, not knowing if the pandemic will ever be controlled, and the constant feeling of uncertainty about the future. They were unsure about their ability to keep their jobs, the risk their partners were facing who were also doctors and treating COVID-19 patients, and not knowing if they would be able to find healthcare if they or a family member got sick. In addition to these fears, the most common fear was a fear of getting sick and dying, leaving their children on their own (Table 4). These fears motivated in many participants the decision to separate from their families to protect them from possible infection. Separation from their families and children left them shouldering an emotional burden of balancing their responsibilities at work and their maternal responsibility.

Another element that was frequently mentioned was a feeling of guilt, whether due to feeling insufficient as a mother, or having to work, or risking bringing the virus home with them. There was the general perception that they were not adequately accomplishing any of their tasks. They also described the internal conflict between being the traditional “ideal woman” (being a good mother, wife, daughter), and their desires for personal and professional development. It is also important to note the self-demanding need to do everything “effectively” (Table 4).

Relationship conflicts were also brought up as a consequence of the pandemic. Most of these conflicts were surrounding a perception of a lack of men’s participation in housework and children’s education. Although before the pandemic women dedicated more time to unpaid household chores and caregiving than men, it seems that COVID-19 made these inequities more apparent (Table 4).

Practicing medicine

As with their family life, coronavirus also affected the professional work of the participants in multiple ways; including different systems for meeting with patients, changes in schedules, worries, as well as stigma facing those who worked with COVID patients. These changes were in addition to requiring permission for leaves of absence, decreased salary, or being fired. The effect of COVID-19 gave rise to many responses like those in Table 4.

Participants’ commentaries showed that in part, the distress was caused by an absence of sensitivity and understanding by the authorities, who lacked strategies for easing the labor (paid and unpaid) put on women’s shoulders during this pandemic.

An additional cause of distress common among the participants was the scarcity of necessary protective equipment for healthcare workers. This caused many to worry about their safety, and in addition they did not receive clear information and received only minimal training to protect themselves and others from the pandemic. An example of this is shown in Table 4.

In addition to all the concerns participants had at work due to changes in methods of seeing patients, inequity, and lack of equipment and support, in Mexico a phenomenon of aggression towards healthcare professionals has developed. The participants discussed their experiences with this aggression, and their fear and anger towards society (Table 4).

Balancing multiple roles

In the participants’ responses, it was clear that they had implemented many strategies to try and balance their professional work, housework, education of their children, and care of children or other family members. Especially for single women, the effort required to balance these multiple roles became overwhelming.

Balancing multiple responsibilities is an additional stressor for healthcare workers, especially for women, who “traditionally” take care of housework and unpaid labor. They have the pressure of being the “natural caretakers” and were required to provide emotional support that is not valued in and out of the home, being often poorly paid at work, and unpaid at home, leaving their own self-care and personal needs to the side (Table 4).

The participants also viewed their burden as clearly unequal between them and their partners and felt as though their husbands primary focus is their work, whether it was in person or virtual, the participants themselves had to divide their time to try and take care of numerous responsibilities. Though inequality is not new, the pandemic and quarantine have made it more evident as is seen in Table 4.

This dual role became more difficult during the pandemic. In many cases, participants lost their support systems, such as parents, grandparents, and friends, due to social distancing. In addition, childcare was harder to find due to fear of infection. There was also evidence of blurred lines between public and private spaces, with the home now being a space for work as well (Table 4).

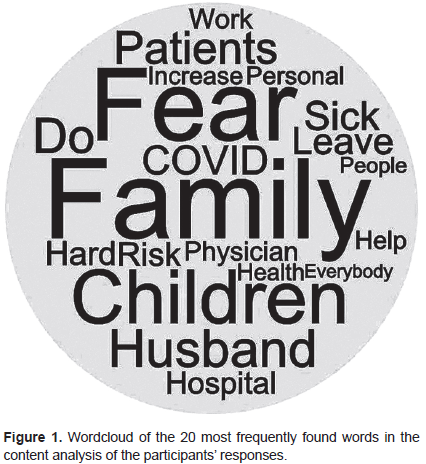

These elements surrounding balancing their role of being a mother with that of a doctor, is summarized in a word cloud created by content analysis of survey responses (Figure 1).

The changes in daily life of the participants clearly affected their schedules and priorities and, as seen in the next section, brought with them a greater risk of mental health problems. In these areas, they had taken on the burden of emergencies related to the care of their family as well as with work, and in many cases, they were also frontline healthcare workers.

Presence of emotional symptoms

Work overload, uncertainty, multitasking, and many other elements present in a humanitarian crisis, such as the COVID-19 pandemic, favor the development of emotional distress. Findings related to this topic are reported in this dimension.

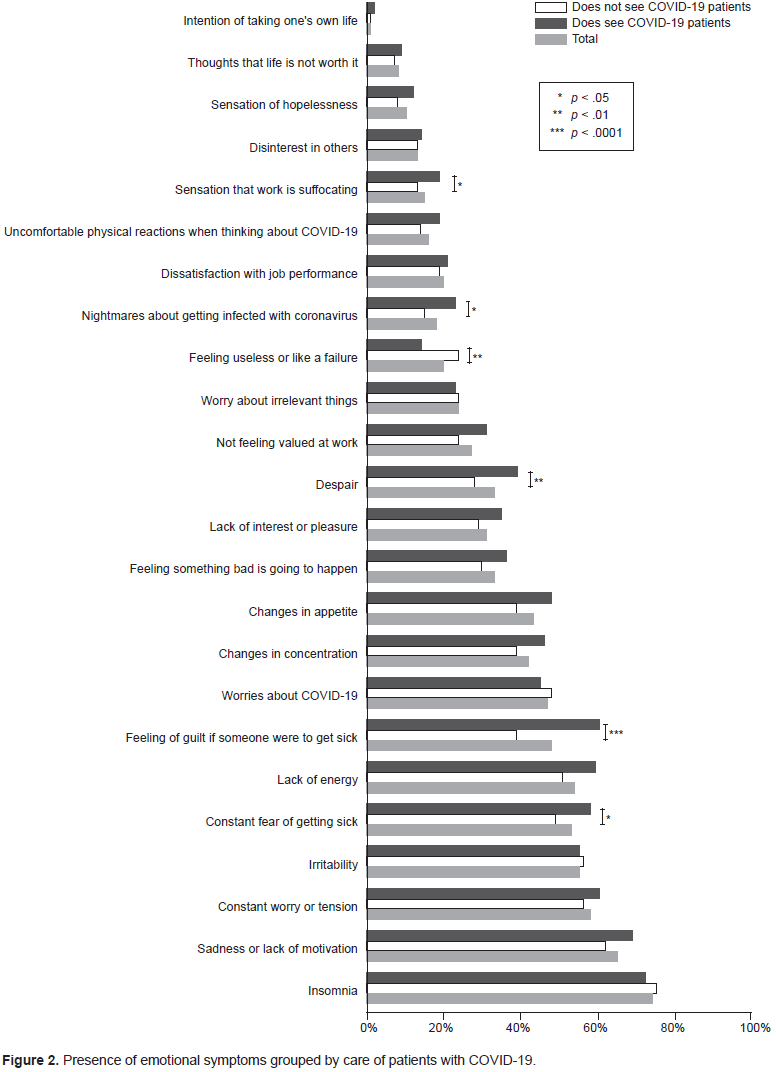

The most frequent symptoms at the time of the evaluation were insomnia, sadness or lack of motivation, and constant worry or tension. Worries that were more frequent in those who saw patients with COVID-19 included constant fear of getting sick (p = .053), thinking that if someone got sick it would be their fault (p < .0001), desperation (p = .007), having nightmares about contracting COVID-19 (p = .020), and the sensation that their work was suffocating (p = .039; Figure 2).

Simple analysis showed a correlation of some factors with the number of emotional symptoms. For example, there was a significant correlation between the number of symptoms and the time dedicated to domestic work, rho (537 = .17, p < .0001) and the time dedicated to childcare, rho(537 = -.20, p < .0001).

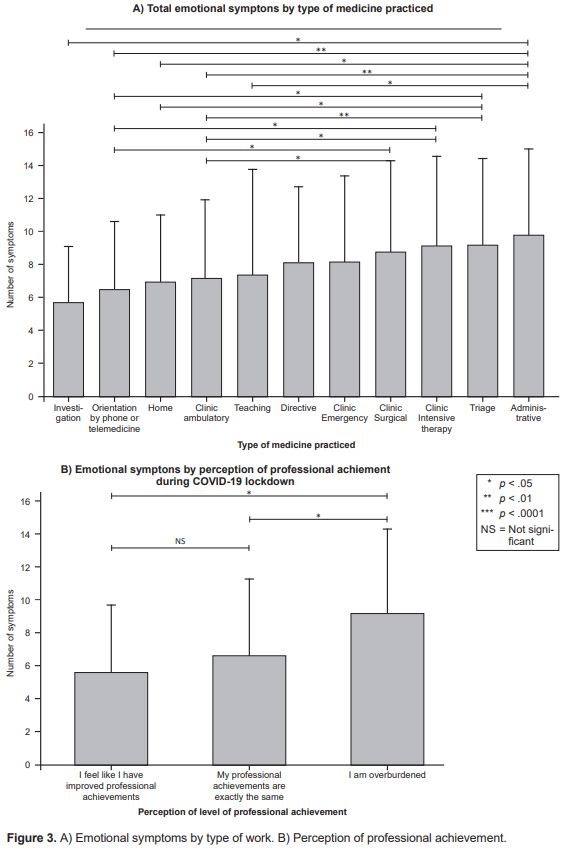

As seen in Figure 3, symptoms were significantly different between participants with different types of work. There were higher numbers of symptoms in participants who conducted administrative work or those who worked in patient triage, intensive care, or surgery (χ2 [10] = 21.54, p = .018). In addition, participants who reported being overburdened at work reported a greater number of symptoms (χ2 [2] = 36.93, p < .0001), showing the effect on their perception of work performance (Figure 3).

Factors associated with fewer emotional symptoms were age (B = -.17, p < .0001) and perception of job achievement (Equal achievement B = -2.21, p < .0001; increased achievement: B = - 3.00, p < .0001); in a significant model, χ2 (26) = 119.02, p < .0001.

Table 4 provides examples of responses from participants regarding these elements and their relationship with emotional symptoms.

It is expected that under conditions of repeated and prolonged anxiety and stress, there is an increased probability for developing mental illness. Therefore, the last section of the results analyzed ideas that participants proposed in order to withstand this crisis.

Strength in the face of adversity

The emotional impact and life dynamics changes that occurred with the onset of the pandemic led to the development of strategies to survive the challenging conditions of this period. In this dimension, those resources that the participants started to work to deal with the pandemic and its effects are described.

When the study was conducted, the pandemic had been spread in Mexico for twelve weeks. At that point, only some of the participants had developed strategies for handling the workload, work and family requirements, and other changes brought by the pandemic. Although they were a minority, some participants discussed reorganizing priorities, finding space for themselves, finding proper protective equipment, putting effort into their social circle (even though it would be virtual), find satisfying activities, find professional support (psychologists or psychiatrist), and knowing that they “aren’t alone.” In these ways, participants were learning how to be mothers and physicians in this new context of COVID-19 (Table 4).

For some participants, the pandemic had provided an opportunity to reconnect with family, spend more time with their children, and participate in activities that previously were not possible. These responses (in the last section of Table 4) included elements that may have influenced the different experience they had during this time, including having social support, a stable and safe job, expression of gratitude by their patients, and building strength from thinking in their children. Their children, although demanding, provided them satisfaction and motivation.

DISCUSSION AND CONCLUSION

With the SARS-COV2 pandemic having impacted people’s lives across the globe, it has especially affected certain sectors of the population, with notable differences by sex (based on traditional gender roles). Working mothers with children face unique challenges (Cluver et al., 2020; Cañongo-León & Palafox-Luévano, 2020), leaving mothers who work as physicians particularly vulnerable (Chowdhry, 2020; Sandven-Thrane, 2020; Staniscuaski et al., 2020; Cluver et al., 2020). COVID-19 has affected the lives of doctor mothers in all realms. Most of these women have had to manage increased childcare, housework, and educational responsibilities, in addition to continuing to work either at home or outside of the home with the worries and risk that come with these obligations. Some lost their job or decided to leave work temporarily or permanently in order to ensure the health of their families, especially their children.

These changes have led to great challenges in reconciling these women’s personal and professional lives, especially with respect to motherhood (Yank et al., 2019). Challenges such as these lead to substantial effects on mental health, with participants in this study mentioning insomnia, constant sadness, stress, or tension; and other distress that has had an effect on their well-being. (López-Atanes et al., 2020; Pappa et al., 2020; Zhang et al., 2020a).

In the United States, since the beginning of the pandemic, Hamel and Salganicoff (2020) found that women with children under 18 years old had experienced more stress than those with older children. Most women (57%) with young children reported that their mental health had gotten worse, as compared to 32% of fathers in the same situation. As mentioned by the authors, these disparities can be related to the difference in work and family responsibilities, which was also expressed by participants in our study.

The double role filled by the participants of this study implies having to divide themselves in many pieces to be able to respond to their different responsibilities. Our study clearly shows how the division between public and private has been blurred. In addition, the “unpaid” labor and family care has been made more visible and exacerbated. The results of this study have shown how in Latino communities, men establish more definitive divisions between work and home than women, whom put their role in the family above their role at work (Amarís-Macías, 2004). Amarís-Macías also discusses how the traditional distribution of roles at home has begun to change, and men whose wives work, take on care of the children to a greater extent. However, women continue to take on more of the household chores than men. Authors such as Cooney (2020) suggest that the pandemic has shown the charade in society that tries to separate work from family life by suggesting that family is a woman’s responsibility, because they chose to be mothers, and it was a personal decision outside of work.

The challenges were clear in reconciling personal and professional lives, especially with respect to motherhood (Yank et al., 2019). In comparison to men, women experience more conflict between work and family in order to conform to social expectations (Zhang et al., 2020a). According to the theory of tension of gender role, women are responsible for family responsibilities rather than men (Jolly et al., 2014; Marchand et al., 2016; Michel, Kotrba, Mitchelson, Clark, & Baltes, 2011). Work-family conflict has numerous antecedents related to the construct (conflict, pressure, variability in work, greater number of working hours, etc.; Eby, Casper, Lockwood, Bordeaux, & Brinley, 2005; Mache, Bernburg, Groneberg, Klapp, & Danzer, 2016).

Work-family conflict has a negative impact on physical and psychological health (Guille et al., 2017) with greater psychological distress. When doctors are overloaded with work for a long period of time, they are unable to fulfill their family responsibilities, and feel guilt and regret. This can deplete personal resources which can result in physiologic and psychological repercussions with long-term negative consequences (mental illness; Juengst et al., 2019; López-Atanes et al., 2020; Staniscuaski et al., 2020; Wenham et al., 2020; Zhang et al., 2020a).

In addition, healthcare workers have the psychological burden of providing emotional support for many others, in addition to their family. It is expected, given their profession of helping, healing, etc., that they are understanding and listen to the problems of their patients and coworkers. During the pandemic, this has become even more frequent, and makes the demands they place on themselves more complicated, which is reflected in the responses of the participants.

Resources such as social support can diminish the mental health effects of work and family demands, as a result of changes perceptions and cognition related to stressors. Support can also moderate the process of understanding stressful people or events, and thus reduce the impact of the stressors on mental health (Tayfur, Bayhan-Karapinar, & Metin-Camgoz, 2013; Zhang et al., 2020a). Nonetheless, when society not only is demanding, but also stigmatizing and aggressive, this resource can become a risk factor.

During the pandemic, healthcare workers were required to be on the front lines and face prejudice and discrimination. For those with children, this is in addition to dilemmas related to childcare, such as school closings. Doctor mothers frequently combined sick days, vacations, and unpaid days off to recover, create a bond with their family, and give their children attention before returning to work, leaving them professionally dissatisfied and exhausted (Juengst et al., 2019; López-Atanes et al., 2020; Staniscuaski et al., 2020; Wenham et al., 2020; Zhang et al., 2020a).

To reduce distress and increase work force retention, healthcare systems should develop new programs to identify and address the needs of these physician mothers. Research in resilience has established that when mothers are under high levels of stress, they must receive continuous care to promote their own well-being, which would favor positive parenting behaviors and a healthy adaptation of their children (Goodman & Garber, 2017). In other words, they should have interpersonal supports integrated into their environments of daily life.

When institutions develop general recommendations to overcome the distress of being a healthcare worker during a pandemic, they should include gender sensitivity, and recognize the differences in stressors between men and women. For example, the recommendation of “spend time with your partner and/or family” could be effective for men but damaging for women. Previous studies show that men may benefit from support from their partner, however women may become more distressed by their marriage and may benefit more from outside support networks (Berg & Upchurch, 2007).

This research raises some questions: 1. What will be the academic and professional impact of this pandemic on doctor mothers? 2. How will the experiences of this crisis impact the work done by women, and will a restructuring of the distribution of this work be possible?

With regards to this last question, the government should include social protection measures to support physician mothers and recognize their work beyond the hospital and office. Although it is often referred to as unpaid labor, this includes housework as well as care of children and older adults. This is the only way to see the crisis as an opportunity to improve the quality of life for women, especially those who participated in this study. This is an opportunity to reduce the gap in the unequal distribution of labor in the home, family, and communities, where having a specific profession or high level of education does not necessarily diminish this gap.

Limitations of this study include using an online survey and a sample of convenience which cannot be representative of all the female physicians or female physician mothers. In addition, the survey design prevented the collection of longitudinal data. There are also no data on doctor fathers or other male physicians, and therefore data cannot be compared from this study to male physicians or those who are not parents. However, to our knowledge, this is the only study that has looked into the impact of the pandemic specifically on physician mothers in Mexico.

Women represent the majority of the work force on the front lines treating patients with COVID-19. The work is exhausting and potentially fatal, especially due to the economic inequalities, underreporting, higher proportion of household work, and higher expectations of child. Design of psychological interventions for doctors managing stressors such as this pandemic should consider gender at all levels.

Interventions and guidelines for care should be sensitive to gender and address the distress that has become even more evident during this pandemic. They should also incorporate strategies such as female empowerment and strengthening the social, economic, and political position of women. Recommendations and public policies should not be generalized, ignoring the different expectations and demands on women and men.

There should be detection and recognition of the differences in requirements put on women so support can be appropriately provided. In addition, work should be done combating gender disparities in the work force to avoid additional psychological damage during this pandemic.