INTRODUCTION

Between 2015 and 2019, 112 to 131 million unintended pregnancies occurred worldwide, with six out of ten ending in abortion. The global abortion rate fluctuates between 36 and 44 abortions per thousand women aged between 15 and 49 (Bearak et al., 2020). In Mexico, this rate is estimated to be 34 per 1,000 women (Singh et al., 2010) The Health Information System shows that the national mortality rate is 40.3 deaths per 100,000 population, ranging from 7.9 in Baja California Sur to 83.3 in Chiapas (Schiavon & Troncoso, 2020).

Although the Total Fertility Rate in Mexico is 2.07 children per woman, it ranges from 1.34 in Mexico City to 2.80 in Chiapas. Among women who have only completed elementary school, it is 2.82, whereas among those who have completed secondary and higher education it is 1.75 (ENADID, 2018). Adolescent women reported that one in two pregnancies was unwanted or unplanned, regardless of whether they already had children. One in five women with fewer children than they considered ideal stated that they had not had more children due to lack of money or for health reasons, whether they lived in a rural or urban setting (ENADID, 2018).

Variability in the epidemiology of abortion and other sexual and reproductive health indicators accounts for the disparities in access to health. The evidence shows that gender, age, ethnicity, social class, and their intersections influence decisions throughout a person’s sexual and reproductive life (Cleeve et al., 2017). The power to freely and responsibly decide about issues that concern one is one of the characteristics of empowerment, known as agency. Empowerment is multidimensional and refers to the expansion of women’s ability to make strategic decisions about their lives, in areas where these decisions were previously limited (Upadhyay et al., 2014).

These limitations are also associated with legal frameworks. The law was changed in Mexico City in 2007 and Legal Interruption of Pregnancy [LIP] (Secretaría de Salud de la Ciudad de México[SEDESA], 2022) services began to be provided. Since 2019, nine states have incorporated changes to make it possible to request an abortion on demand in the first trimester. For the remaining health needs, the legislation varies enormously (Centro Nacional de Equidad de Género y Salud Reproductiva, 2022).

In 2021, the Mexican Supreme Court of Justice set a historic, nationwide precedent, recognizing reproductive autonomy as a right protected by the Constitution and defining it as “All the choices that give meaning to the life project of people as free beings, within the scope of a morally plural, secular state,” including “the choice of and free access to all forms of contraception, assisted reproduction techniques and the possible interruption of pregnancy” (Suprema Corte de Justicia de la Nación, 2022). The Court argued that health determinants and other structural conditions could obstruct the elements required to prevent an unwanted pregnancy and concluded by indicating the need for health services to exist to exercise the right to decide.

In Mexico, seeking a LIP service has been associated with sociodemographic characteristics such as being a student, having a job, and having other children (Figueroa-Lara et al., 2012). Qualitative reports indicate that worrying about having another child is associated with having more caregiving tasks and distributing them among family members, as well as having to share the household income with another member of the family nucleus. Caregiving and parenting tasks are perceived as a barrier to professional development (Helfferich et al., 2014).

In Mexico City, from April 2007 to May 2023, among those attended at LIP facilities, the highest proportion (45%) were between 18 and 24 years old; 43% had completed high school, 70% had at least one child, one in two (54%) was single, 29% were living with their partners and 11% were married. One in three (30%) were homemakers, 24% were students and 29% were employees (SEDESA, 2022).

This study explores how the determinants of sexual and reproductive health influence the control women have over their behaviors and how experiences of power dynamics significantly influence reproductive outcomes. Accordingly, this study considers that the presence of adverse economic, reproductive, and psychosocial experiences can make it difficult for women legally terminating a pregnancy to exercise reproductive autonomy.

METHOD

Design of the study

Cross-sectional study that is the baseline of a prospective, longitudinal study designed to determine the prevalence of a probable major depressive episode in women who legally interrupted a pregnancy and received medication at a public facility in Mexico City.

Participants

Two hundred and seventy-four women who met the following criteria: being over 15, resident in Mexico City, who had attended their discharge/follow-up appointments and agreed to participate in the interview. Exclusion criteria included having had an abortion by manual vacuum aspiration, having a serious intellectual or motor disability that prevented them from answering, and having requested the LIP for other legal reasons (rape, danger to the woman’s life, genetic malformation).

Measurements

Semi-structured interviews based on a questionnaire that included ad hoc questions and a battery.

Sociodemographic characteristics. Age (open), educational attainment and occupation (closed multiple choice), socioeconomic level (assigned by the Medical Administration and Hospital Information System), current relationship (dichotomous).

Reproductive characteristics. Age at first pregnancy, number of children (open), previous induced abortions and whether they had agreed with their partners to undergo the LIP (closed multiple choice).

Psychosocial characteristics. For current depressive symptoms, the 35-item version of the Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale, (González-Forteza et al., 2011) was used. Designed by Radloff in 1977, it was validated among the Mexican pregnant adolescent population (Lara et al., 2006), and adapted to the DSM-IV criteria using 35 items that explore the nine symptoms and their presence in the past two weeks (Ramos-Lira et al., 2001) and women who had terminated their pregnancies (α = .93; Ramos-Lira et al., 2023). Response options ranged from “0 days” to “8 to 14 days.” At the end, subjects were asked “In the past twelve months, have you had symptoms like those I just mentioned and for so long and with such intensity that you would say you were depressed?” with dichotomous response options. A question about the perception of their mother’s depression was also included from the adaptation de Lara et al. (2006): “Has your mother been or was she depressed? This means that she has shown symptoms such as feeling lonely, sad, or not wanting to do anything with such intensity and for so long that you would think she was depressed,” with dichotomous response options.

Intimate partner violence in the past twelve months was evaluated with four dichotomous items (Ramos-Lira & Saltijeral Méndez, 2008). For this analysis, a single variable was created, considering the presence of at least one (α = .72). For sexual violence in childhood, subjects were asked, “Before you turned 15, did anyone –whether or not they were a member of your family– ever touch you, or touch or caress any part of your body;” “Did they touch any part of your body or have sexual relations with you when you were very young or against your will?” (Ramos-Lira et al., 2023). Response options were dichotomous.

The Individual Abortion Stigma Scale (Cockrill et al., 2013) was also included, focusing on women who have had an abortion, and validated in clinics in the United States in its 20-item version (α = .88) in four subscales: Worries (α = .94), Isolation (α = .83), Self-criticism (α = .84), and Community rejection (α = .78). The score is continuous, with a potential range of 1 to 4.35, meaning that the higher the score, the greater the stigma. It has been tested in Nigeria, Germany, Uruguay, Kenya, and Mexico to evaluate interventions, services, and public policies (Wollum et al., 2021).

Procedure

Data were collected at a hospital affiliated to the Mexico City Ministry of Health between November 2018 and December 2019. Interviews, conducted during the follow-up appointment, two weeks after the abortion, lasted from 40 to 60 minutes. The interviewers and the social worker assigned to the LIP facility invited subjects to participate. After accepting, they were taken to a cubicle where the informed consent form was read to them.

Statistical analysis

Stata 16.0 was used for the Latent Class Analysis (LCA), which estimates conditional probabilities of belonging to a population segment, given that each person has specific behavior. Regression models evaluate the contributions of each observed variable based on membership of this segment (Monroy Cazorla et al., 2009), which is particularly useful in small samples (Reyna & Brussino, 2011; Strunin et al., 2015; Cordero-Oropeza et al., 2021).

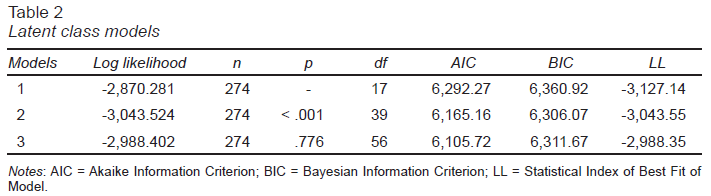

Three models were evaluated through the Bayesian Information Criteria (BIC), weighting the goodness of fit of the model through the maximum likelihood (ML) value. Parsimony was evaluated using the Akaike information criteria (Monroy Cazorla et al., 2009). Finally, a regression analysis was performed using the stigma score as the dependent variable.

Ethical considerations

Ethical approval was obtained from the Research Ethics Committee of the Ramón de la Fuente Muñiz National Institute of Psychiatry, on June 4, 2018: CEI/C/037/2018.

RESULTS

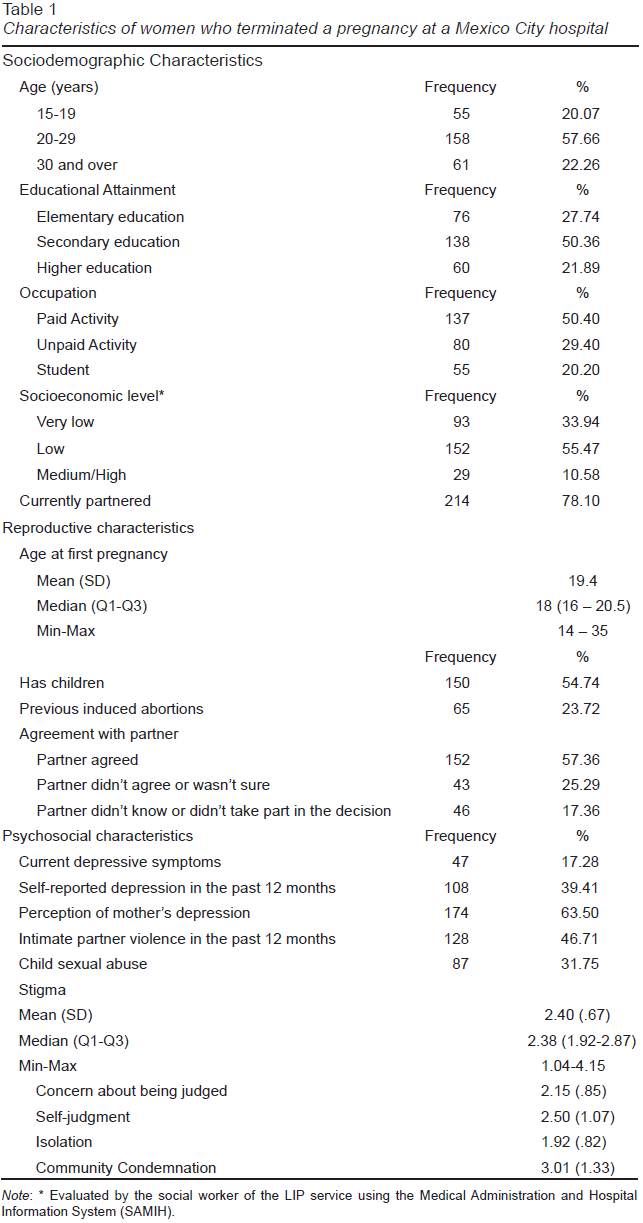

Table 1 shows the characteristics of the subjects. The two-class model was chosen because it provided the best fit, was the most parsimonious, and showed statistically significant differences (Table 2).

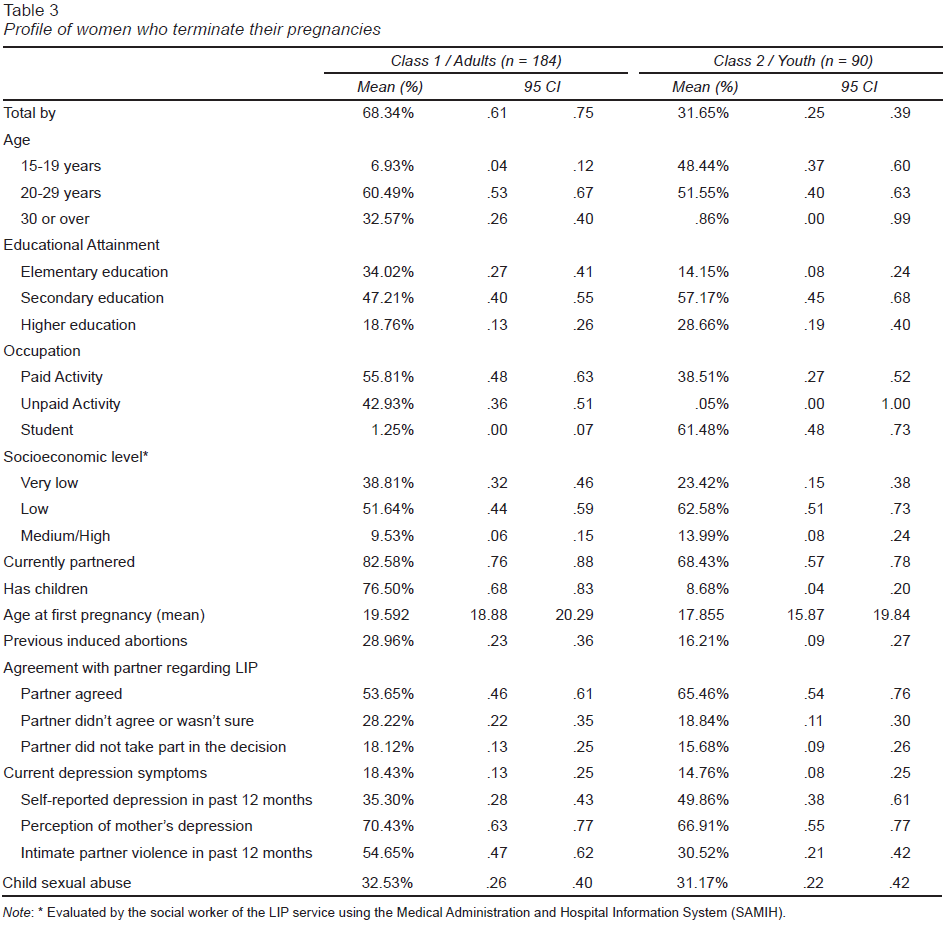

Table 3 shows two classes. The first comprises 68.34% of the women while the second contains 31.65% (p < .01). The profile for the first group included a larger proportion of adult women, with a higher proportion of those who had completed basic education (34% vs. 14.1%). Eight out of ten had stable partners, 76.5% had at least one child, had had their first pregnancy at an average age of 19.5 and over half their partners had agreed for them to undergo a LIP (53.65%). The majority displayed severe depressive symptoms at the time of the interview (18.4% vs. 14.8%) and had perceived their mothers as being depressed at some point in their lives (70.4 vs. 66.9%), while 54.6% had experienced intimate partner violence in the previous 12 months.

Conversely, the group of young women were high school or university students (57.2% and 28.7% respectively) and less likely to report being partnered, 8.7% had children and 16.2% had had at least one induced abortion. Their first pregnancy at been at the age of 17.8 years. A total of 4.8% of those with partners reported that they had agreed to the interruption of their pregnancy. Although young women were more likely than adult women to have perceived themselves as being more frequently depressed in the past twelve months (49.9% vs. 35.3%), after the abortion they reported high symptoms of depression less frequently (14.8%). They had experienced comparatively less violence from their partners in the past year (30.5%; Table 3).

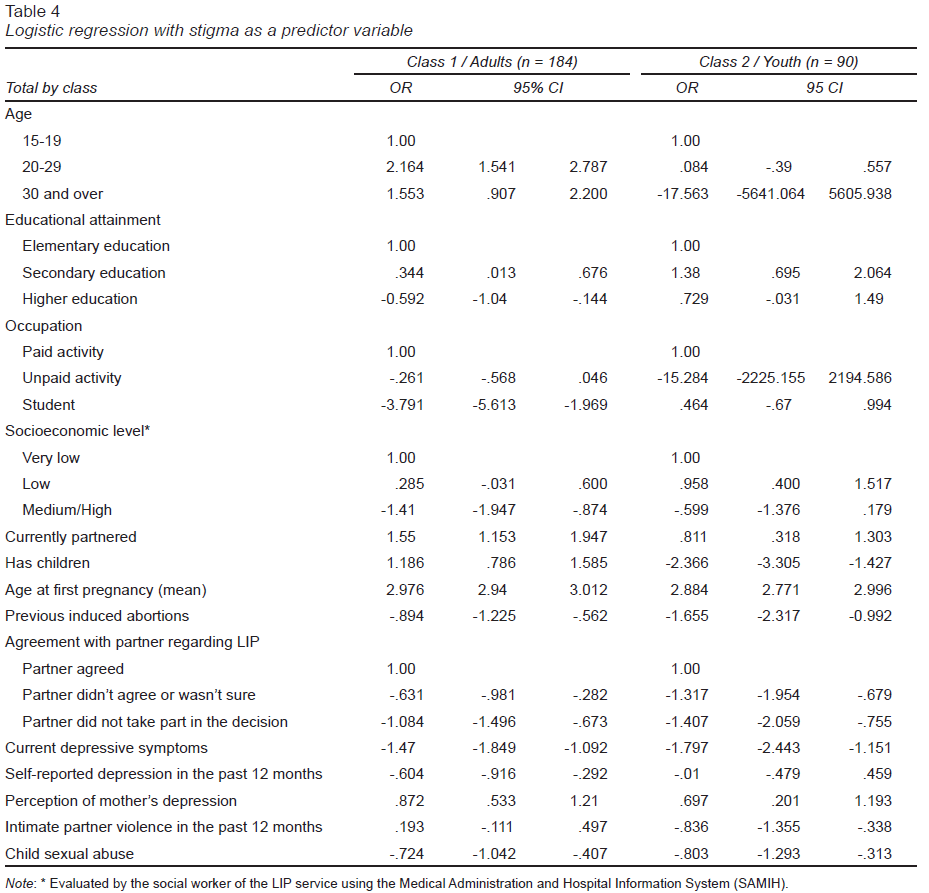

In regression, the stigma score was inversely associated in young women (f[x] = -.5056, p = .02). In other words, young women who had terminated their pregnancies were less likely to perceive themselves as stigmatized. Table 4 also shows that experiences prior to abortion differ between the two classes. In the case of young women, having children, having had induced abortions, disagreeing with their partners, or having partners who had not taken part in the decision, having experienced intimate partner violence in the past twelve months and/or having been a survivor of childhood sexual abuse, were inversely related to the probability of having high stigma scores. Conversely, among adult women, being aged between 20 and 29 years old, having a partner and having become pregnant for the first time before turning 20, was associated with the probability of presenting greater stigma (Table 4).

DISCUSSION AND CONCLUSION

Latent class analysis identified different behavioral patterns in women who terminate their pregnancies. Stigmatization remains a central element in the barriers to obtaining an abortion, access to which is constructed as shameful, immoral, and deviant (Cullen & Korolczuk, 2019). The scale used showed adequate psychometric properties (α = .88 - α = .98) coinciding with previous reports on the Mexican population (Ramos-Lira et al., 2023; Belfrague et al., 2020).

As in Table 1, in the study by Cockrill et al., (2013), self-criticism and community condemnation obtained the highest scores. In a systematic review by Hanschmidt et al., (2016), self-criticism is classified as internalized stigma (what women think about themselves) and social condemnation as perceived stigma (the anticipation of negative judgment from others regarding their decision, which could be loved ones, healthcare providers, or people in general). In the case of healthcare providers, stigma has been described in dimensions such as discrimination, management disclosure, and resilience (Martin et al., 2018).

In findings about women who had had an abortion, the total scale score was significantly and inversely associated with age, as in the present study. Moreover, it was positively associated with religiosity, particularly with the social condemnation subscale (Cockrill et al., 2013). This agrees with studies in non-Western countries reporting high community rejection of older or married women or those who already have children (Makleff et al., 2019), which would appear to be linked to the idealization of motherhood and religiosity (Orihuela-Cortés et al., 2023; Sorhaindo et al., 2014). However, it may also be associated with experience, since abusive practices exercised by providers towards women seeking service have been documented (Collado Miranda & Mora-Ríos, 2020).

Reproductive experience also proved relevant. Having had a previously induced abortion decreases the probability of high stigma, whereas having had a first pregnancy at age 19 increases it. A study conducted with Catholic women who had had abortions shows that they defended “selective motherhood” against absolutist Catholic discourse by having a contextual moral approach, anchored in everyday circumstances such as a precarious financial situation, maternal work, and unstable interpersonal conditions (Singer, 2018).

The contents of Table 4 could support the hypothesis of Norris et al. (2011) that women find a number of reasons to have an abortion, with some reasons being more socially sanctioned and therefore eliciting a less harsh judgment. Situations such as living in adverse circumstances such as being depressed, disagreeing with their partners, or having experienced violence are situations associated with unwanted pregnancy (Steinberg, 2016). The decision to have an abortion is therefore a means of eliminating the stress associated with an unwanted pregnancy and may create a sense of relief rather than a negative experience (Major et al., 2009).

Among adults, being aged between 20 and 29 years old, having higher education, being a student and having a medium/high socioeconomic level was inversely associated with the probability of greater stigma (Table 4), which coincides with what found by Figueroa-Lara et al. (2012), who document that in Mexico, seeking LIP services is associated with years of schooling, being a student, and being engaged in paid employment. A qualitative study in Germany showed that younger women regarded having a child as barrier to gaining financial independence, completing their education and improving their social status (Helfferich et al., 2014). A five-year longitudinal study conducted in the United States showed that women with the greatest financial difficulties are those who seek an abortion and when they do not obtain one and continue an unintended pregnancy, they are also those who face the greatest risk of unemployment, poverty and assuming the responsibility of raising a child without a partner (Biggs et al., 2013; Finer et al., 2005; Kirkman et al., 2009).

Being partnered was associated with the risk of having higher levels of stigma in adults (Table 4), although not in young women, who reported a higher proportion of agreement (Table 3). Making the decision independently of their partners decreased the probability of high stigma scores in both classes. This coincides with the result of a study of German women, which found that the stability of a relationship was associated with the common, consensual decision of whether or not to have children. (Helfferich et al., 2014). In this respect, Chibber et al. (2014), report that 26% of women declared that their partner could not or did not want to help them have a baby, because they were not physically close enough to be able to support then, were not financially capable of providing, “were not ready to become fathers” or were not “responsible enough” to parent, or did not help the woman raise her existing children.

Adult women may make the decision to abort without consulting their partners and for financial reasons that discourage them from having more children. Conversely, young women do so because they regard having a child as constraining their life project or likely to cause family problems because they are single (Chibber et al., 2014). In this respect, it would appear that when a woman has a stable partner, reproductive autonomy, conceptualized as a personal decision-making capacity, is associated with better communication skills and less disparity (Upadhyay et al., 2014).

Experiences of violence were associated with the lowest probability of high stigma, which is consistent with what was reported by Stockman et al. (2013) that violence could impact women’s ability to decide about their sexuality and reproduction. In a meta-analysis of reproductive coercion (Grace & Anderson, 2016), one of the consistent conclusions is that unintended pregnancy is higher among those being coerced by their current partners.

It is striking that the proportion of child sexual abuse among the adult and young women in this study is higher (32.53% and 31.17% respectively) than that reported by other studies in Mexico, which hovers around the 10% mark (INEGI, 2022; Valdez-Santiago et al., 2020) and that in both groups, it is inversely proportional to stigma. A greater presence of adversities in childhood is associated with having multiple abortions (Steinberg et al., 2016) and subsequently experiencing intimate partner violence or sexual victimization (Stockman et al., 2013).

Stigma has been described as the most significant predictor of depression both internationally (Biggs et al., 2020; Major et al., 2000; OʼDonnell et al., 2018; Steinberg et al., 2016) and nationally (Moreno López et al., 2019; Ramos-Lira et al., 2023). However, the results of this study coincide with the results of a qualitative study on women who underwent an LIP in Mexico City. Subjects, particularly young women, mentioned that although abortion was a difficult situation, it constituted a source of satisfaction since they had managed to solve a serious problem in their lives and their decision meant they had prioritized their health and well-being (Sorhaindo et al., 2016). The high percentage of perceived maternal depression is striking in view of the existing evidence on the intergenerational transmission of depression, a phenomenon that requires further study in terms of its mechanisms and protective factors (Goodman, 2020).

The main limitation of this study is the intentional selection of the sample, which only includes women who used medication and were cared for by highly specialized personnel exclusively dedicated to performing these procedures.

The results underline the significance of the stigma attached to abortion in reproductive decision-making, even in contexts of legality and standard procedures. Stigma mechanisms do not appear to be reproduced in the same way among the generations of women interviewed. Providing counseling focused on demystifying erroneous or distorted ideas about abortion, within the context of the connection with experiences in the individual sexual and reproductive trajectory, should be a priority for public policy in this sphere.