INTRODUCTION

Residing outside one’s country of origin without legal documentation places people in a state of acute vulnerability (Critelli & Yalim, 2023; Reyes Miranda et al., 2015). Nearly 50% of the 12 million Mexican immigrants registered in the U.S. are undocumented (CONAPO, 2018), crucially affecting their well-being because they are often stigmatized and marginalized (Reyes Miranda et al., 2015), unable to apply for social benefits, and at a high risk of being hyper-exploited at work (Critelli & Yalim, 2023). This situation constitutes systemic racism, also called institutional or structural racism (Venegas León et al., 2023). Mexican and other Latin American groups experience interpersonal and structural racism, defined as “the totality of ways in which societies foster [race-based] discrimination via mutually reinforcing systems (as in housing, education, employment, earnings, benefits, credit, media, health care and criminal justice)” (Cerda et al., 2023, p. S72). For Young and Crookes (2023), immigration policy is a mechanism of structural racism based on racial inequality. “The U.S. system of racial hierarchy is created by the power of a White-dominant society” (p. S17).

Although this structural racism existed in pre-Trump administrations, under Trump, the rhetoric “normalized” interpersonal racism. “Recent studies show that the increase in anti-immigrant policies in the United States and their focus on the segment of Mexican origin are exacerbating discrimination against the Latino population in general and the Mexican population in particular” (Pérez-Soria, 2022, p. 192).

The threat of deportation and migration-related losses, such as family separation, are associated with emotional discomfort, which can manifest in psychological and somatic symptoms and adverse effects on identity and self-esteem (García, 2018; Garcini, 2016; Phipps et al., 2022). In her theoretical framework, Mabel Burin (1995) reflects on the gender condition of women and their oppression, using the concept of discomfort as a category of analysis to address the mental health of men and women, defining it as a subjective sensation of psychic suffering that does not fit within the classic criteria of health or disease. From this perspective, it can be understood as a form of resistance to unequal structural conditions associated with gender. “Most scholars who analyze this problem insist on highlighting how female gender roles affect women’s ways of getting sick. Among the most widely studied gender roles are the maternal role, the conjugal role, the role of housewife, and the dual social role of the domestic and extra-domestic worker (creating double shifts) (Burin, 2010, section 3).” In the case of undocumented Mexican immigrants (UMIs), the structural conditions of inequality they face because of their immigration status, together with their ethnicity and place of origin, interact with the individual’s need to survive and adapt to a particular cultural/societal milieu and can influence the level of stress they experience as a result (Asnaani et al., 2021). Inter-personal discrimination due to undocumented status has been reported to be the main predictor of clinically significant psychological distress, even greater than a history of trauma (Garcini et al., 2019).

Despite the above, these populations generally fail to seek care in formal health services (Payan, 2022; Tenorio Corro & Arredondo, 2018), either due to the conditions of the U.S. health system or to perceived barriers such as the fear of being detained in these services due to their immigration status, misinformation, the language barrier or high costs of services, time available, distance and lack of transportation (Rastogi et al., 2012; Held et al., 2020).

What do migrants do to cope with emotional discomfort if they do not seek formal support? Stress refers to the problems or strains people encounter throughout life, while coping refers to the behavioral or cognitive responses used to manage stress (Lazarus & Folkman, 1986). Coping is a process used to deal with stressful or problematic experiences. In the case of Latin American immigrants, self-medication is common practice (Wolcott-MacCausland et al., 2020). However, this strategy is designed to reduce physical rather than emotional discomfort. For the latter, strategies such as transnational social networks have been identified (Rios Casas et al., 2020), together with “viewing bad things in a positive light,” “obtaining comfort from someone in the community” (Cobb et al., 2016), cognitively resignifying undocumented status using spirituality and optimism, and expressing pride in one’s cultural identity (Garcini et al., 2022). Undocumented Latino immigrants are more likely to use religion as a resource in times of need (Sanchez et al., 2015). Indeed, religious coping appears to be related to emotional well-being in undocumented Mexican immigrants since praying is regarded as an active request for help (Abraído-Lanza et al., 2004).

Since these studies have mainly been conducted in areas with a long migratory tradition, the objective of this article is to explore the sources of emotional discomfort and the coping strategies used by undocumented Mexican migrants living in two states on the East Coast that have hardly been researched due to their relatively recent migration history.

METHOD

Study Design

The present paper is the result of a qualitative study comprising two phases, in each of which different methodological strategies were used. The first involved exploring and describing the contexts in which UMIs lead their everyday lives and contacting key informants, while the second consisted of semi-structured interviews with undocumented Mexican immigrants. The principal investigator (MM) was already familiar with the area since she had previously traveled to Washington DC to participate in other mental health projects and to visit relatives living in Maryland. She is a psychologist by training and a researcher in medical sciences with a master’s degree in public health and a doctoral student in public mental health, and introduced herself as such to the study participants. In addition, she has trained as an interviewer in other projects as an interviewer and is qualified to give emotional containment. She conducted the fieldwork from April to August 2019, contacting key informants for the first time during the first two months.

The Context

The study site consisted of two counties located in two states on the East Coast: Maryland and Virginia, which form part of the corridor from Florida to New York that is still in the stage of development as a region of Mexican immigration (CONAPO, 2018). Most undocumented immigrants living in Maryland and Virginia are Salvadoran (30% and 27%) or Mexican (9% and 13%). Maryland County, where the study was conducted, reported 6,000 UMIs (MPI, 2019a) with Virginia reporting 19,000 (MPI, 2019b).

In both counties, the undocumented population is engaged in similar activities, with women working in house cleaning and men in gardening and construction. Both sexes are also often employed in the food sector (restaurants). The places where immigrants meet are small shopping malls serving the Latino population, where Spanish is spoken. There is usually a beauty salon, a laundromat, a place for sending remittances, a Mexican or Salvadoran restaurant, and a grocery store selling meat, vegetables, fruit, bread, and typical products from Mexico and Central America.

Participants

In phase one, four Latina women, two from each county, who were managers or owners of commercial establishments serving the Latino population, served as key informants. They asked potential participants whether the first author (MM) could contact them individually, and whether they preferred her to go to the informant’s home or call them by phone (the number of which had been provided by the key informants) to make an appointment and explain the objectives of the study in more detail.

In the second phase, three undocumented Mexican immigrants were contacted and interviewed. After that, they referred four other participants, yielding a final sample of three men and four women. No participant referred by the key informants had an employment relationship with any of them.

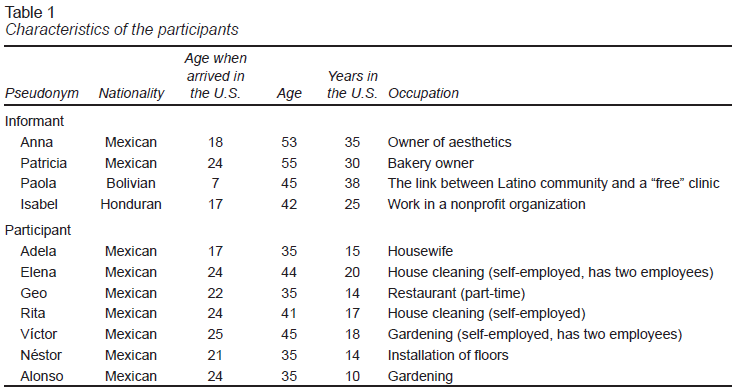

The inclusion criteria were (a) being an undocumented Mexican immigrant, (b) being over 18 years old, and (c) providing their informed consent to participate. Table 1 shows their main characteristics.

Data Collection Procedure and Techniques

The first phase included ethnographic techniques, such as participant observation, field notes, and open interviews. MM toured the two study areas on foot. The observations, based on a guide, were designed to record the main places and activities performed by the UMIs at their usual shopping malls and supermarkets, restaurants and bakeries, convenience stores, schools, recreational centers and parks, churches, and community or other types of centers offering health services. At the same time, informal conversations were held with the attendees and managers of these places, and when possible, meetings were attended. This procedure made it possible to establish contact with key informants who had daily contact with and knowledge of the population of interest. After earning their trust, MM paid each of them two formal visits. In the first one, she briefly explained the study and what their participation would involve, and if they showed interest in the study, a second visit was arranged. During the latter, the letter of consent to which they had verbally agreed was read out. MM explained her interest in exploring the mental health of UMIs living in their county and, in particular, in securing their collaboration for contacting potential Mexican migrants to participate in the interviews.

The second phase involved a semi-structured interview with UMIs using a thematic guide based on the problem statement, research objectives, literature review, and pilot interviews. The axes of exploration of the interviews were emotional discomfort, the primary sources of concern in everyday life as an immigrant, and the strategies used to cope with them.

The place and date of the semi-structured interviews were agreed on with each participant separately. All of them were interviewed in their homes without the presence of other people, in a session lasting 60 to 120 minutes. An informed consent form was read out to them requesting their authorization to participate and for the interviews to be audiotaped. Because of their immigration status and to ensure anonymity, they gave their authorization with a pseudonym. They were assured that report documents or publications would not contain information that could reveal their identity.

At the end of the interview, the interviewees were thanked for their participation and offered a free online session with a Mexican psychologist experienced in working with migrants. Although the participants appreciated the interest and attention given to their stories, the proposed session was optional. Participants did not feel emotionally harmed by the interview and instead were grateful for having been heard.

Analysis

The open-ended interviews with key informants were not transcribed or analyzed. The information collected during this phase was recorded in field diaries and used to triangulate information between discreet observations of everyday life and direct, planned interviews (Denzin & Lincoln, 2000).

MM and another independent transcriber transcribed the recordings. The two of them reviewed the audiotape of each interview, comparing each pair of transcripts to check the consistency of the text obtained and ensure that it could be read as a conversation. Data were analyzed using thematic analysis. This is a method for systematically identifying and organizing information on patterns of meaning and analyzing the subjective meanings of participants (Braun & Clarke, 2012; Flick, 2015) so that it can be used with various theoretical frameworks (Flick, 2015).

For this study, both an inductive and a deductive approach were used. In other words, the topics and codes were first constructed based on the contents of the transcripts of the seven interviewees. These issues were subsequently reviewed, considering emotional discomfort and coping strategies regarding the source of discomfort (regardless of whether they were associated with their undocumented status) (Chaves, 2005). We used the six-phase approach (Braun & Clarke, 2012) recommended to identify the emotional discomfort experienced by these immigrants, the situations to which it was linked, and the strategies employed to cope with it. Three authors of this manuscript (MM, MTS, LRL) individually reviewed each interview and participated in the first and second approaches for the themes identified and to construct categories and subcategories. They subsequently met to discuss them and arrive at a consensus through researcher triangulation (Benavides & Gómez-Restrepo, 2005).

Subcategories that emerged from emotional discomfort and ways of coping with it were considered in regard to the aforementioned subcategories of the source of discomfort, regardless of whether the latter was associated with undocumented status.

Ethical Considerations

This project was evaluated and approved by the Research Ethics Committee of the Ramón de la Fuente National Institute of Psychiatry (CONBIOÉTICA-09-CEI-010-20170316) and subsequently validated by the University of Maryland in Baltimore.

RESULTS

Concerns Affecting Mental Health

From the perspective of the key informants, the concerns of undocumented Mexican migrants affecting their mental health can be divided into two main areas: being separated from their families and the fear and difficulties they experience because of their undocumented status in the United States, particularly the emotional discomfort caused by driving without a license due to the fear of being detained and deported.

As for the migrants themselves, the main emotions related to these stressors and the strategies used to cope with them are described in Table 2.

The Emotional Discomforts of Everyday Life

Relaxing and listening to songs of praise: The sadness and loneliness of the role of caregiver and housewife

The most significant source of discomfort was the burden of child-raising mentioned only by the women, who expressed a series of emotions and sensations associated with sadness, loneliness, and feeling misunderstood. One of them, with four children, described the lack of support she felt from her husband, who works in a nearby city, meaning that they only see each other on weekends, mentioning a degree of hopelessness that has even led her to contemplate suicide:

"... When I feel sad, I feel like my husband doesn’t even care about me... It just affects me that my husband is not with us... (as he) works far in a different city. So it is as if I was gripped by despair that everything had to be done by me... I know he has to go to work but (I wish that) it was not so far away! From Monday to Friday, he leaves me completely on my own... And then despair gripped me, and I said, ‘Ah, what if I killed myself because then all my problems would end’...” (Adela).

In regard to strategies for dealing with this discomfort, listening to songs of praise (using CDs or cell phone apps) and relaxation activities were reported, such as being alone or looking for spaces without children, which the women mentioned as a means of coping with the burden of parenting and household activities. Since it is difficult for them to achieve this type of space due to the lack of close support networks, this discomfort can often become chronic. All the interviewees mentioned that they would like to have their mother or sisters nearby to help them look after their children.

Praying and crying: feeling unable to cope with financial difficulties

In regard to everyday financial problems, such as insufficient income, another participant remarked that her salary is insufficient to support two children since her ex-husband does not pay alimony:

"... (Here in the U.S.) you can’t get ahead, you can’t save, so that’s where your frustration comes from, I mean... that I’m working and working on the same thing and I don’t make any progress... So, I sometimes ask myself, why God? Why do I work so much and see no results for my efforts?... With so many expenses! Because what this country gives with one hand it takes away with the other.” (Rita).

In response to this type of stressor, the most common strategy, in addition to crying, is religious strategies such as praying for a divine power to help people advance.

The Emotional Discomfort Associated with Undocumented Status

Praying and crying: The fear of going out and being deported

Fear is the main form of discomfort; all participants feel it when they leave for work or go out, mainly because of the risk of being detained and deported if they commit a traffic offence despite having a driver’s license. Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) and the police, in general, are the main sources of their fear. One participant describes this as follows:

“... you go out, and honestly you look all around you and, well, are thinking that they are following you or that (...), I do not know, (hoping) that you do not have an accident because they will immediately call ICE or who knows what ... But yes, it affects you because you get up and from the moment you get up ..., you think this, hopefully I’ll be alright, and nothing will happen to me and they won’t get me out there because I would have to go back.’...” (Nestor).

Spiritual or religious strategies are often used to cope with the fear of driving and being detained or deported because of their immigration status: entrusting oneself to God and thinking that “if it is going to happen, so be it,” “they are going to send me to my country, to a place I know.” However, participants with young children did not mention this strategy. The religious activities mentioned by the four participants included praying and attending church.

As one participant noted:

“... I start to think, not everything God wants to happen happens, does it? Already, if God says that, that’s fine. Well, since I used to go to church, now I don’t but before I did, I remember a little bit of that, of God, and I pray, or I prefer not to talk to anyone ... Of course, no, I don’t want to talk to anyone, I shut myself away, if I have time I shut myself away, I rarely have time to be alone, but if I have time I shut myself away and pray ... like God gives you encouragement... and I calm down, I try to calm down...” (Adela).

These fears increased when they learned that raids had taken place in their area and were accompanied by insomnia and constant worry. As a result, they focused on social avoidance strategies, such as not watching the news and not leaving home.

Gritting one’s teeth and bearing it: Feeling anger and resisting the urge to react to racism and discrimination

The racism and discrimination experienced because of being of Mexican origin or because of their skin color were cited as being both common and taking place on a daily basis, when they went shopping, or were at their children’s schools or work. The associated discomfort reported was a mixture of anger and helplessness.

“... Racism can cause emotional discomfort... a lot of Americans look at you as if you were a weirdo, you know? That’s what can cause you discomfort, you know...” (Victor).

“... We were working, mowing the lawn outside a bank, and at the end, I produced some dust, and (an American) tried to attack me, shouting nasty things at me, telling me that he was going to call the police because we had dirtied his car. He almost hit me, he yelled at me, he came very close, stood next to me and shouted at me (jabbing his finger at me), to leave his country ...” (Alonso).

Faced with these episodes, participants mainly used self-control strategies, such as gritting their teeth and keeping quiet (“aguantarse”), to avoid problems with the police or at work when they were reported if they defended themselves. However, they added that their immigration status and the fact that they are not proficient in English also leads to a sense of helplessness and anger, as they are unable to cope with these specific situations of discrimination. It is important to note that UMIs cannot change these situations, so the best thing they can do is control themselves and avoid reacting. To ask for respect or, even worse, to shout or do something against the people who engage in these acts of discrimination can lead to jail or deportation.

Avoiding but also looking for social support: The sadness and loneliness due to being away from their families

Another form of discomfort associated with immigration status was the sadness in women due to their loneliness because of being away from their families of origin or in men because of not having a wife and children in the United States. Some participants said that they could count on their neighbors but did not discuss their problems with them. All the women interviewed said that they would like to have their mother or sisters nearby to help them raise their children.

One participant emphasized the feeling of not having someone to help them cope with their loneliness:

“... I miss being around family. When I feel lonely (in Mexico), I go to my mom’s house, my aunt’s house, or I think of somewhere to go, but I go to someone in my family’s house. Where am I supposed to go? There is no-one here...” (Adela).

The use of avoidance strategies such as sleeping and waiting for the feelings of sadness or discomfort to disappear were strategies specifically reported by men for this discomfort. They seek social networks, although not necessarily to talk about their discomfort, but mainly to distract themselves. Women said that they did not trust their neighbors enough to share their personal problems with them. The women reported that they phoned their mothers or relatives in Mexico to tell them about their problems.

Strategies such as self-medication and home remedies were only reported for dealing with physical discomfort. Tylenol, aspirin, and vitamins, the most common types of medication used, are obtained at Latino stores or sent from Mexico with “raiteros” (informal couriers). Four interviewees were from Oaxaca, from the same community of origin, located in the Papaloapan Basin region, and now residing in Maryland. They use the services of the “raitero,” who is a transnational resource since he delivers goods between this Oaxacan community and the United States. It would be worth investigating this resource as a possible migration circuit.

As observed, none of the participants mentioned using formal mental health services to deal with emotional discomfort, despite the existence of mobile health services (such as “Mission of Mercy”) and low-cost services (such as “Loudoun Free Clinic”) observed during the initial phase. In the interviews with UMIs, they argued that they were not accessible due to various barriers, such as their high cost and the need to miss work, which would affect their income. In addition, none of them had health insurance, unlike their US-born children. Men said that mental health care was not something they would consider.

DISCUSSION AND CONCLUSION

The emotional discomfort of Mexican immigrants was mainly associated with being undocumented and comprised distrust and fear of having their legal status discovered and being detained or deported as a result (Garcini et al., 2021; Payan, 2022). It is striking that both subtle acts of discrimination experienced on a daily basis –which can be considered “racial microaggressions” (Sue et al., 2007)– and overtly racist actions were mentioned. The latter targeted their skin color or ethnicity, in other words being/looking Mexican or “Latino.”

Following what Garcini et al. (2021) reported, this study found that undocumented immigrants experience many types of discomfort due to constant stressors such as socioeconomic disadvantage, harsh living conditions, demanding work schedules, double shifts, stigma, and discrimination, coupled with anti-immigrant rhetoric, policies and actions that increase distress, fear, and mistrust among undocumented communities (Garcini et al., 2021). Participants not only mentioned specific events but also the constant feeling of insecurity and hypervigilance, due to the permanent threat of raids or being questioned by ICE. This was compounded by the feeling of being overwhelmed and powerless in some cases due to the mistreatment of Mexicans shown on television and social networks (Pinedo et al., 2021).

As noted, the fieldwork was conducted shortly after Donald Trump took office and ended days after a massacre with racist overtones in Texas.1 In this political context, operations to locate and deport the undocumented increased (Carrasco, 2017; Armendares, 2018; Armendares & Moreno-Brid, 2019), with cases of racial profiling by immigration agencies that resulted in many Latinos being detained and questioned about their citizenship or legal immigration status (Pinedo et al., 2021). All this was accompanied by anti-immigrant, anti-Mexican rhetoric (Garcini et al., 2021; Payan, 2022).

Racist incidents had already been experienced by some participants before the Trump administration, showing that their ethnicity and irregular migrant status put them in vulnerable situations regardless of the government in power. These migrants can therefore be said to experience structural vulnerability since a crucial part of adverse mental health outcomes, in this case, daily emotional discomfort, are not the result of individual or cultural failure but rather of social, political, and economic structures (Cadenas et al., 2021; Garcini et al., 2019), largely due to the aggressive immigration policy and harsh enforcement of laws (Payan, 2022). It is therefore important to note that the strategies of self-control (such as gritting their teeth and bearing it) used by participants to cope with emotional discomfort help them deal with their situation as undocumented migrants, but not to resolve it, since this depends more on a complex socio-political structural system than on their efforts. These coping strategies should not therefore necessarily be considered “passive” or a sign that immigrants assume the role of victims (Abraído-Lanza et al., 2004).

Women reported the stress and discomfort associated with the burden of raising children, in which they perceived a lack of support from their partners and missed having the support of their families of origin. They mentioned relaxation activities to cope with this burden, while “sleeping” and “letting sadness pass” were the strategies reported by men. In his literature review, Payan (2022) reports that distraction (such as engaging in activities to avoid thinking about the problem) is an effective strategy for coping with mental health problems.

Another strategy mentioned by most participants, especially to cope with the fear of driving and being detained or deported because of their immigration status, was to entrust themselves to God and think that “If it is going to happen, so be it.” Religious coping refers to specific cognitive acts resulting from the religious beliefs of people who deal with stressors (Tix & Frazier, 1998). As mentioned earlier, these are mechanisms reported to be important to the mental health of undocumented immigrants, particularly Latinos (Campbell et al., 2009; Garcini et al., 2021; Payan, 2022). Given that many aspects of these immigrants’ lives are perceived as uncontrollable, it is hardly surprising that they use emotional coping strategies, such as religiosity, if they lack close social support. This may also be related to the more frequent and significant reports of religious coping in women. However, it has been found that Latina and Mexican women tend to use this coping more than non-Latina women (Abraído-Lanza et al., 2004) and Mexican men (Ramos-Lira et al., 2020), respectively.

The lack of social support networks has been identified as the main risk factor for mental health in these populations (Garcini et al., 2021). In addition, limited family support due to being separated from the family of origin has been identified as a factor associated with problems with child-raising, increasing stress (Garcini et al., 2021). In this regard, in general, recent immigrant Mexican women experience more negative consequences on their mental health when they are separated from their families (Arenas et al., 2021).

Since undocumented Mexican migrants in this area do not have a long-standing migratory tradition as they do in other states, there are no migrant groups or community organizations, particularly in the county in Maryland. At the time of the study, collective agency was not observed, unlike in other states where communities of Mexican origin have existed for decades, as in California. However, there is a capacity for individual agency that will probably be transformed and eventually lead to the establishment of an organization.

As expected, striking differences were found between the men and women participating in this study, due to the traditional gender roles adopted by the participants, which seem to determine the way they cope with difficult situations and become sick. Key aspects include the importance of caring for others in women and economic and job stability as an expression of manhood in men (Burin, 1995; Ojeda García et al., 2009).

What undocumented migrants do to cope with the oppression caused by the enormous power structures legitimized by the United States is to look for the cracks or small spaces where they can move, establish networks with each other, and survive on a day to day basis without necessarily considering obtaining legal residence. The strategies reported work as a band-aid, in other words, a temporary remedy (Sangaramoorthy, 2018), since they fail to address broader long-term needs (Redfield, 2017) requiring public policies.

One limitation of the study is that since it focused on a group of undocumented Mexicans in a specific region of the United States it does not represent this population in general. However, this approach gives an idea of what people with similar immigration status experience daily. Accessing participants was done carefully, prioritizing their safety. Moreover, it was an advantage that the principal investigator was Mexican with Spanish as her first language. The use of ethnographic strategies during fieldwork helped participants feel confident during the interviews. However, some did not delve into their stories, and men especially were unwilling to address issues related to painful emotions.

In short, the best thing would be for migrants living in the United States to access services that meet their needs. Giacco et al. (2014) propose collaboration and information sharing between mental health services and non-medical services, integrating mental health care with physical care and psycho-educational family programs to increase help-seeking and engagement with services in immigrant populations. They also note that technology-based interventions can help support information translation, reach underserved populations, and deliver culturally adapted programs. In this regard, telemedicine could be an option for meeting these mental health needs, including training health personnel in the specific care of the undocumented migrant population. At the same time, it is essential to promote online and in-person social networks in the face of the enormous loneliness these migrants with few mobility options can experience daily both within the United States and on their return to Mexico.