INTRODUCTION

Scientific evidence has highlighted the link between adverse life events and mental health, showing that post-traumatic responses range from psychopathology to post-traumatic growth. However, understanding these post-traumatic responses requires the study of the risk/protective factors and mediators explaining the mechanisms for the development and maintenance of psychological disorders. For this reason, the factors involved in the ability to recover from exposure to stressful or traumatic events have been studied. The findings show that the relationship between external demands (possible stressors) and the impact on mental health is mediated by transdiagnostic psychological variables acting as either protective (Hilko & Chalder, 2018; Sandín et al., 2009) or risk factors (Tyra et al., 2021).

The COVID-19 pandemic saw a worldwide increase in depression symptoms, post-traumatic stress, confusion, worry and anger (Brooks et al., 2020; Czeisler et al., 2021; Chávez-Valdez et al., 2021; Rodríguez-Quiroga et al., 2020; Santomauro et al., 2021), mainly in individuals with a previous psychiatric diagnosis or vulnerability factor (Campos et al., 2021). Women in particular experienced a greater psychological impact (Akel et al., 2021; Al-Jbouri et al., 2021; Demissie & Bitew, 2021; Galindo-Vázquez et al., 2020; Pérez-Cano et al., 2020; Wang et al., 2020). This was due to various risk factors that increase their vulnerability, such as limited access to health services, social inequality, reproductive problems, parenting and family care, as well as domestic violence (Almeida et al., 2020; Brooks et al., 2020; Connor et al., 2020; Dlamini, 2021; Rodríguez-Quiroga et al., 2020; Sediri et al., 2020; Thibaut & van Wijngaarden-Cremers, 2020).

Gender violence is one of the stressors most commonly reported by women. This phenomenon occurs across all societies, social classes and cultural levels (United Nations Entity for Gender Equality and the Empowerment of Women [UN Women], 2021; World Health Organization [WHO], 2021; Sardinha et al., 2022). During the COVID-19 pandemic, there was a sudden increase in the manifestations of violence against women (Dlamini, 2021; Piquero et al., 2021). Indeed, it was reported that at least 243 million women experienced sexual and/or physical violence at the hands of their partners (UN Women, 2020). In Mexico, the incidence of domestic violence has also risen. between 2019 and 2021, there was an increase in emergency calls regarding violence perpetrated against women. Violence against women rose by 47% (from 197,693 to 291,331), sexual abuse increased by 15% (from 5,347 to 6,169) while sexual harassment expanded by 27% (from 7,470 to 9,505). Although there has been no increase in emergency calls regarding intimate partner violence, numbers have remained high (2019: 274,487; 2021: 259,452; SSPC, 2020).

These situations of violence can cause emotional consequences, such as anxiety, depression, worry, Post Traumatic Stress Symptoms (PTSS) and Post Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) (Almeida et al., 2020; Chávez-Valdez et al., 2021; Davey, 1994; Liu et al., 2020; Wang et al., 2020). Repetitive negative thinking, such as worry, is a persistent thinking style and transdiagnostic cognitive mechanism contributing to personal distress, negative emotional states, and emotional maladjustment. Researchers have studied how the dimension of worry is present in female victims of violence and tends to predict the development of PTSS (Cabras et al., 2020; UN Women, 2020) following exposure to trauma (Neria et al., 2008). It is estimated that 31% to 84% of victims of gender-based violence develop symptoms of post-traumatic stress disorder (Coker et al., 2005; Karakurt et al., 2014), together with re-experiencing, avoidance (cognitive and behavioral) and living with a sense of threat (Huerta Rosales et al., 2014; Irizarry & Rivero, 2018; Neria et al., 2008).

Likewise, one of the main factors associated with PTSD after a traumatic event is emotional dysregulation (Paulus et al., 2018; Pencea et al., 2020; Seligowski et al., 2015; Tull et al., 2011). This is defined as a transdiagnostic difficulty that can directly affect health since the individual shows a low acceptance of emotional experiences, limited ability to inhibit impulsive behaviors when negative emotions are experienced, unwillingness to experience negative emotions as part of life and poor strategies for modulating their emotions (Gratz & Roemer, 2004; Villalta et al., 2020). These alterations significantly contribute to the deterioration and distress of trauma survivors (Berking & Whitley, 2014; Cloitre et al., 2013; Coker et al., 2005; Tyra et al., 2021; Yiğit & Guzey-Yiğit, 2019).

Women experience multiple episodes of adverse events linked to violence. Women who have experienced intimate partner violence from different perpetrators showed a pattern of greater difficulty with emotional regulation (Lilly et al., 2014; Muñoz-Rivas et al., 2021; Ruork et al., 2021). In victims of sexual violence, emotional dysregulation is a predictor of risky sexual practices after trauma, together with negative self-concept and interpersonal problems correlating with PTSS (Holladay et al., 2021). It is therefore suggested that the effect of these transdiagnostic variables be investigated to improve interventions that not only focus on PTSS, but also on aspects of emotional dysregulation, especially in the first few months after the trauma, since this would contribute to an improvement in people’s lives and a reduction of trauma (Cloitre et al., 2013; Gilmore et al., 2020; Messman-Moore et al., 2010; Villalta et al., 2020). Other prospective studies have shown that emotional dysregulation is associated with and predicts the development of PTSD symptoms, in both the first three months (Forbes et al., 2020) and the first year after trauma (Pencea et al., 2020), even when controlling for other PTSD risk factors, such as age, race, ethnicity, childhood trauma, lifetime trauma exposure (exposure to traumatic events), number of stressful events experienced, type of interpersonal trauma, level and intensity of symptoms of depression and PTSD at the time of the stressful life event (Forbes et al., 2020; Pencea et al., 2020). In addition, during the COVID-19 emergency, the mediating role of emotional dysregulation in PTSS related to COVID-19, specifically in regard to the heterogeneity of symptoms, has been demonstrated (Siegel et al., 2021; Tyra et al., 2021; Velotti et al., 2021).

In this respect, dimensional cognitive variables, particularly emotional dysregulation and worry in adult life, may be associated with the development or manifestation of various forms of psychopathology (Bardeen et al., 2013; Tull et al., 2011). There is evidence of a robust relationship between negative emotions, difficulties in emotional regulation and the severity of post-traumatic stress symptoms (PTSS) in people exposed to different types of traumas (McLean & Foa, 2017). Seligowski et al. (2015) analyzed fifty-seven studies and obtained seventy-four effect sizes by testing eight random-effects models. The largest effects were seen for general emotional dysregulation, rumination, thought suppression and experiential avoidance, while medium effects were found for expressive suppression and worry. The findings of this meta-analysis suggest that various aspects of emotion regulation are associated with PTSS symptoms in a variety of samples (type of trauma).

However, more research is required to understand the nature of post-traumatic reactions and the underlying psycho-emotional processes. It is therefore relevant to explore transdiagnostic variables, such as worry and emotional dysregulation, to examine how women cope with stressful events that impact emotion regulation difficulties, and whether these difficulties subsequently contribute to PTSS. Improved understanding of the mediators linked to emotional regulation strategies and worry when experiencing a stressful event could reveal modifiable risk factors for reducing PTSD symptoms among women exposed to high-risk traumas, such as those stemming from violence.

Based on the previous findings, this study aimed to determine whether emotional dysregulation and worry mediate the association between type of stressful event and posttraumatic stress symptoms. The following hypotheses were proposed. First, trauma derived from violence (such as physical and sexual assault) would be associated with greater emotional dysregulation and worry compared to other types of traumas (specifically, family problems or separation). Second, emotional dysregulation and worry would mediate the relationship between experiences of stressful events and posttraumatic stress symptoms in adult women.

METHOD

Study design

A non-experimental, quantitative, correlational, cross-sectional study was conducted using multiple regression, with a non-probabilistic sample of 687 women ages 18 to 76. The present cross-sectional study was part of a larger research/intervention study exploring clinical factors of Mexican people seeking online psychological support for people experiencing any kind of emotional or stress-related disorder.

Participants

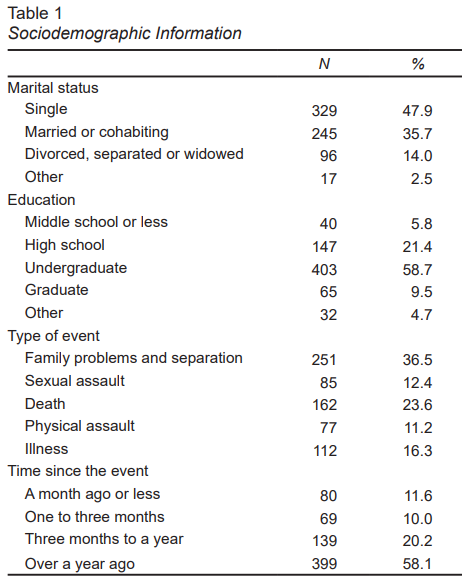

Non-probability sampling yielded 687 female participants ages 18 to 76 (M = 31.74, SD = 9.94) who were community members recruited from a larger randomized clinical trial investigating the efficacy of an online transdiagnostic psychological treatment for emotional and trauma-related disorders. Since this was a secondary analysis, sample size was not determined a priori but was dependent on that of the larger project. For the current study, participants were selected if they had experienced exposure to trauma according to the Posttraumatic Stress Disorder Checklist for DSM-5 (PCL-5). Participants were not required to demonstrate high PTSS or a PTSD diagnosis. Sociodemographic information on the sample is presented in Table 1.

Procedure

Participants were recruited from the community via social networks (such as social media advertisements on Facebook) from March 2021 to April 2022. To take part in the study, they were required to fill out a questionnaire on SurveyMonkey (which presented the scales in random order to prevent fatigue). The study was advertised as an online psychotherapy intervention for emotional disorders. Although it included subsequent phases, the online baseline data were used for this study. Before taking part in the study, participants were informed about its aims and provided electronic informed consent. Because of the nature of the online intervention study, the data were not anonymized. However, access to the database was limited to the principal investigator and two assistants. Anonymized versions of the data were created for research purposes.

Measures

Difficulties in Emotion Regulation Scale (DERS; Gratz & Roemer, 2004). This is a thirty-six-item, self-report measure assessing individuals’ typical levels of emotional dysregulation across six domains: nonacceptance of negative emotions, difficulty engaging in goal-directed behaviors when distressed, difficulty controlling impulsive behaviors when distressed, limited access to emotion regulation strategies perceived as effective, and lack of emotional awareness, and lack of emotional clarity. Items are rated on a five-point Likert scale, with higher scores indicating greater emotional dysregulation. The Mexican version has adequate internal consistency with an α = .80. It consists of fifteen items, comprising difficulties in emotion regulation as well as emotional awareness (De la Rosa-Gómez et al., 2021). Only the fourteen items measuring difficulties in emotion regulation were used in this study.

Penn State Worry Questionnaire (PSWQ-11; Meyer et al., 1990). The PSWQ measures the frequency and intensity of worry. The original questionnaire includes sixteen items rated on a 1–5 scale (1 = Not at all typical of me, 5 = Very typical of me). The brief version (PSWQ-11), adapted and validated in Spain, comprises eleven items (Sandín et al., 2009). In the Mexican population, the PSWQ-11 obtained a better model fit than the original questionnaire (PSWQ-16) and an adequate internal consistency coefficient (α = .88; Padros-Blazquez et al., 2018).

Posttraumatic Stress Disorder Checklist for DSM-5 (PCL-5; Weathers et al., 2013). The PCL-5 is a self-report measure to determine the symptom severity of PTSD, with twenty items reflecting the DSM-5 diagnostic criteria of PTSD. Individuals are asked how much they have been bothered by each item over the past month. Items are scored on a Likert scale ranging from 0 to 4, with higher scores indicating more acute PTSD symptoms. The checklist has adequate internal consistency for psychometric properties in the Mexican population, with an alpha of .97, as well as appropriate convergent validity (rs = .58 to .88; Durón-Figueroa et al., 2019). It is important to note that this instrument only assesses symptoms related to post-traumatic stress, rather than providing a diagnosis of PTSD itself. Consequently, PCL-5 scores should be interpreted from a dimensional perspective, rather than being regarded as the basis for clinical diagnosis.

Stressful life events. Participants answered the following open-ended question: Sometimes people experience difficult situations that create a high degree of stress. Please think of a stressful or threatening event you experienced at some point in your life that continues to cause you emotional distress. If you remember more than one, try to focus on the one that causes you the most emotional distress. Write what this event was below. Additionally, to determine the time of the event, participants were asked: How long ago did it happen? with options 1 = A month ago or less, 2 = One to three months, 3 = Three months to a year, 4 = Over a year ago. Adverse events were classified as family problems and separation, sexual assault, death, physical assault, and illness. This coding process was independently conducted by two research assistants, following coding instructions previously developed by the research team. Discrepancies were reviewed by two authors (AHP and PDV) to reach a consensus.

Statistical analyses

First, univariate summary statistics (mean, SD), as well as bivariate correlations were calculated for continuous variables. The bivariate association between type of event and PTSS was also examined, for which an ANOVA test was used. For the mediation analysis, family problems and separation was chosen as the reference category for the type of event variable. Four dummy binary variables were therefore created for type of event. The statistical significance of the indirect effects was evaluated through bias-corrected 95% RI obtained from 5000 bootstrap samples. Time since the event was also included as a control variable in the model, with ≥ 1 year as the reference category. Given the random order in which measures were presented, missing data were assumed to be missing completely at random (MCAR), so that only participants with complete data were included (n = 687).

Ethical considerations

This study uses data collected before randomization and treatment onset. Procedures were approved by the institution’s Research Ethics Committee (CE/FESI/ 082020/1363), and the study has been registered with Clinical Trials (NCT05081830). All participants read and agreed to an electronic consent form before completing the self-report questionnaires online. Only adults ages eighteen or older were allowed to register. No confidential data were required from participants such as their names, addresses or telephone numbers.

RESULTS

Preliminary analyses

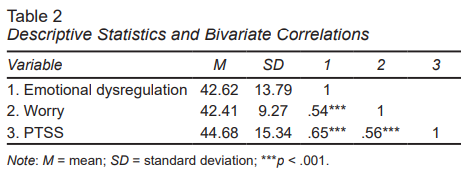

The zero-order correlations between emotional dysregulation, worry and PTSS were all strong and statistically significant (Table 2). The strongest correlation was between emotional dysregulation and PTSS (r = .65, p < .001). PTSS mean scores differed significantly between the five types of event (family problems and separation, sexual assault, death, physical assault, and illness), F(4, 682) = 3.21, p = .013, η2 = .02.

Mediation model

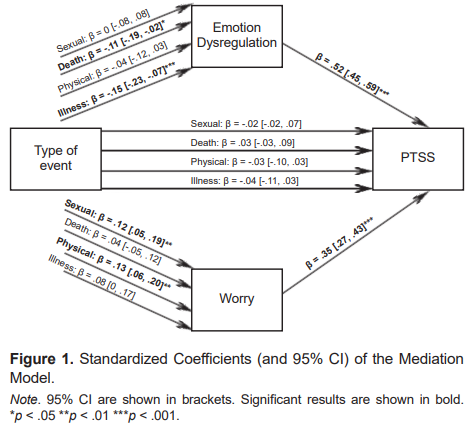

Figure 1 presents the results of the mediation model. Both emotional dysregulation and worry were positively associated with PTSS. Sexual and physical assault were associated with greater worry. Death-and illness-related events were significantly associated with emotional dysregulation. The indirect effect of sexual events on PTSS through worry was statistically significant (Unstandardized a*b = 1.80, 95% CI [0.73, 3.12]), suggesting that experiencing these events leads to higher levels of worry, which, in turn, increase PTSS. Similarly, the mediating role of worry on the association between physical events and PTSS was also significant (Unstandardized a*b = 1.96, 95% CI [0.83, 3.29]). As for emotional dysregulation, the indirect effect of death-related events on PTSS was significant (Unstandardized a*b = -1.84, 95% CI [-3.40, -0.38]). Emotional dysregulation also mediated the relationship between illness-related events and PTSS (Unstandardized a*b = -3.00, 95% CI [-4.86, -1.33]). Finally, although not shown in Figure 1, time since the event was also included as a control variable, although no statistically significant association was found with regard to PTSS.

DISCUSSION AND CONCLUSION

The principal purpose of this study was to assess whether emotional dysregulation and worry mediate the relationship between experiences of stressful events and PTSS within a sample of adult Mexican women seeking online psychological treatment. The results confirm the hypothesis that emotional dysregulation and worry mediate the relationship between experiences of various types of trauma and PTSS. However, an analysis by dimension and type of event found that emotional dysregulation mediated the relationship between death and illness-related events and PTSS, but not sexual and physical assault in our sample of women. These findings were not consistent with previous research, which found that emotional dysregulation mediated the relationship between sexual assault trauma and PTSS (Raudales et al., 2019; Seligowski et al., 2015). Nevertheless, the sample in this study could have been influenced by the increase in illness and deaths due to COVID-19 (Domínguez-Rodríguez et al., 2022). Although there was an increase in violence against women during the COVID-19 pandemic (Dlamini, 2021; Piquero et al., 2021), particularly sexual and/or physical violence by their partners (UN Women, 2020), our results show that sexual and physical assault were not significantly associated with emotional dysregulation. This could be explained by previous findings of women survivors of intimate partner violence suggesting that emotional dysregulation is a better predictor of PTSS than type of abuse (Ruork et al., 2021). Nevertheless, an alternative interpretation is also plausible. Some of the literature suggests that interpersonal trauma has a more substantial impact on emotional dysregulation than non-interpersonal traumatic events (Ehring & Quack, 2010; Raudales et al., 2019). This could explain why events linked to death and illness, which are arguably non-interpersonal, displayed a weaker association with dysregulation than events related to family problems. Notably, instances of sexual and physical violence showed no significant differences when compared to family problems, all of which involve interpersonal events.

Findings highlight the importance of emotional difficulties in PTSS development. Specifically, the study demonstrated the mediating role of worry in the association between sexual and physical assault and PTSS. These findings could be explained by the fact that repetitive negative thoughts, such as worry, increase vulnerability to PTSD (Ardino et al. 2013; McEvoy et al., 2013). Worry involves thoughts about the future (Olatunji et al., 2010) which, when associated with having been a victim of sexual and physical abuse, affect problem-solving and healthy information processing, contributing to the development of PTSS (Neria et al., 2008). Similar studies report that adult women with a history of sexual assault showed intrusive thoughts related to abuse (Rosenthal et al., 2006). Worry increased the severity of PTSS as a strategy for controlling unpleasant thoughts of the traumatic event. It is therefore suggested that female victims of violence often make chronic attempts to avoid unpleasant internal experiences (such as thoughts, emotions, and memories) as a means of regulation.

Although some studies have reported that time since the stressful traumatic event has been associated with higher PTSS (Feeny et al., 2000), in our study, although time since the event was included as a control variable, no statistically significant association with PTSS was found. However, it is known that potentially traumatic stressful life events can hamper the development and consolidation of adaptive emotional regulation strategies, particularly in victims of sexual abuse who live with or depend on the aggressor (such as relatives, bosses, and partners), who learn to normalize abuse as a coping strategy through avoidance, emotional numbing, submission, guilt, and worry. However, over time, these strategies cease to be functional and the discomfort becomes chronic, manifesting itself in difficulty in recognizing and regulating emotions (Freyd et al., 2001). Accordingly, additional research is required to assess the impact of various trauma types on the development of emotional dysregulation, including worry and other dimensional variables in women in various contexts.

These are some of the limitations that must be considered for a better understanding of research findings. In the first place, the sample consisted only of women, which, although they were the target population due to the relevance of the study phenomenon, means that the results cannot be generalized. Second, a structured instrument was not employed to measure types of stressful events. Instead, an open-ended question was used that had to be coded and grouped into common categories at the discretion of the researchers, meaning that they could have been some bias in the classification of stressors. Future studies should use a specific instrument to measure the type and severity of stressful life events. Along these same lines, data were collected cross-sectionally and therefore do not provide evidence of a temporal relationship between emotional dysregulation, worry, and PTSS. Although this study suggests the presence of a possible mediating variable, it is not possible to evaluate this relationship thoroughly. It is suggested that future studies be longitudinal and use larger samples to specifically determine whether stressor types via emotional dysregulation and worry mediate the development and severity of PTSS in women. Finally, this study was a secondary data analysis using data from a larger study designed to provide online psychological treatment in a context impacted by the COVID-19 pandemic. Some variables of interest (such as additional emotion regulation strategies) could therefore not be included, since they were not part of the primary study.

Difficulties in emotional regulation and worry are well-established correlates of anxiety and depression that act as risk factors for the development of PTSD and its continuation. This study contributes to the current models of psychopathology and intervention programs, specifically those focusing on transdiagnostic models and emotional dysregulation, a significant treatment target for stress and trauma-related disorders.