Salud mental 2025;

ISSN: 0185-3325

DOI: 10.17711/SM.0185-3325.2025.006

Received: 9 January 2024

Accepted: 23 July 2024

Psychometric Properties of Tools for Assessing Spirituality: A Scoping Review

Kevin J. Aya-Roa1 , Vicente Beltrán-Campos1 , María de Lourdes García-Campo1 , Lina María Vargas-Escobar2 , José Ángel Hernández-Mariano3

1 División de Ciencias de la Salud e Ingeniería. Campus Celaya Salvatierra. Universidad de Guanajuato, Celaya, Guanajuato, México.

2 Facultad de Enfermería. Universidad El Bosque; Bogotá, Colombia.

3 División de Investigación, Hospital Juárez de México. Ciudad de México, México.

Correspondence: Vicente Beltrán-Campos División de Ciencias de la Salud e Ingeniería. Campus Celaya Salvatierra. Universidad de Guanajuato. 38090 Celaya, Guanajuato, México Phone (Work): +52 (461) 598 5922 Mobile phone (personal): +52 (461)183 6220 Email: vbeltran@ugto.mx

Abstract:

Background The study of spirituality has gained importance, as it correlates with mental health and coping strategies, particularly at times of vulnerability. Spirituality could therefore contribute to the development of interventions to improve people’s quality of life. Experts often base the development of interventions and treatments on instruments measuring constructs such as spiritual well-being, which requires validated, reliable instruments.

Objective. This scoping review sought to summarize the evidence in the literature on the instruments available to assess spirituality in different groups and evaluate the content and psychometric properties of these instruments.

Method. A search was conducted on PubMed, Virtual Health Library (VHL), Elsevier, Springer, Scopus, and Google Scholar databases, using a combination of keywords such as “spirituality,” “validation study,” and “psychometrics.” The search was restricted to studies published in English and Spanish from January 2013 to March 2023.

Results. Sixty-four studies were included in this review. Two categories of analysis were established, the first being constructs related to spirituality and instruments for their measurement, in which a total of 22 conceptual constructs were found. The second was the validity and reliability of the instruments, in which it was found that most studies only assessed construct validity.

Discussion and conclusion. Given the complexity of the phenomenon, many instruments lack conceptual boundaries, resulting in similarities between items in instruments measuring different constructs. Determining the attributes and dimensions for the accurate measurement of spirituality is essential.

Keywords: Spirituality, health surveys, psychometrics, review.

Resumen:

Antecedentes. Actualmente, el estudio de la espiritualidad ha cobrado relevancia ya que se correlaciona con la salud mental y estrategias de afrontamiento, especialmente en situaciones vulnerables de la vida. Comprender este fenómeno podría ayudar al desarrollo de intervenciones para mejorar la calidad de vida de las personas y, por ende, se requiere de instrumentos validados y confiables para la medición de la espiritualidad.

Objetivo. Se realizó una revisión de alcance para sintetizar la evidencia sobre los instrumentos disponibles para valorar la espiritualidad en diferentes grupos de personas y evaluar el contenido y propiedades psicométricas de estos instrumentos.

Método. Se condujo una búsqueda en las bases de datos PubMed, Biblioteca Virtual en Salud, Elsevier, Springer, Scopus y Google Scholar, utilizando los términos “espiritualidad”, “estudio de validación” y “psicometría”. La búsqueda se limitó a estudios publicados en inglés y español desde enero de 2013 hasta marzo de 2023.

Resultados. Se incluyeron 64 estudios. Se establecieron dos categorías de análisis: la primera categoría son los constructos relacionados con la espiritualidad y sus instrumentos de medición, donde se encontraron un total de 22 constructos conceptuales, y la segunda categoría es la validez y confiabilidad de los instrumentos en la que se encontró que la mayoría de los estudios únicamente evaluaron validez de constructo.

Discusión y conclusión. Dada la complejidad del fenómeno, muchos instrumentos carecen de una delimitación conceptual, lo que propicia similitudes entre los ítems de instrumentos que miden diferentes constructos Es necesario delimitar los atributos y dimensiones para una adecuada medición de la espiritualidad.

Palabras clave: Espiritualidad, encuestas de salud, psicometría, revisión.

BACKGROUND

As holistic beings, humans have multiple dimensions, including the physical, mental, social, and spiritual, the last of which develops differently in each individual (Morales Contreras & Palencia Sierra, 2021). Spirituality as a dimension allows one to not only connect with a belief system, a higher self, or whatever we consider divine but also with those around us and the environment (Fuentes et al., 2018). Spirituality transcends the intra-, inter-, and transpersonal dimensions of human beings. Despite being abstract, it is essential. Cultivating spirituality is important for people to achieve health and well-being (de Diego-Cordero et al., 2022). Individuals who fail to develop their spirituality fully or comprehensively may struggle to find life satisfaction (Caccia & Elgier, 2020).

Spirituality is a factor in achieving transcendence, which in turn leads to states of mental well-being in the individual (Reed, 2018, 2021) expressed through feelings of wholeness, meaning, fulfillment, and mental health (Reed & Haugan, 2021). Incorporating spiritual care into practice is therefore part of comprehensive, holistic care (Morales Contreras & Palencia Sierra, 2021).

In this respect, it is essential to have valid, reliable measurement instruments with scientific, methodological rigor to enhance the practice of health professionals and research in this area. These instruments should be able to assess subjective attributes with complex dimensions for the health-disease process of the population and concepts as significant as spirituality (Muñiz & Fonseca-Pedrero, 2019).

Measurement instruments delimit the definition of the concepts to distinguish them from others (Epstein et al., 2015). This facilitates the operationalization of variables and promotes coherence between concepts, constructs, dimensions, and items or empirical indicators (Herdman et al., 1998). Moreover, the design and validation of instruments for abstract phenomena unifies definitions according to a theoretical or conceptual point of reference, thereby avoiding using, misusing, or confusing similar terms and providing guidelines for developing new research (Sánchez-Villena et al., 2021).

Spirituality is increasingly being incorporated into clinical practice at various levels of care (Pagán-Torres, 2022). There are several measurement instruments assessing spirituality from different theoretical and philosophical perspectives. One example is Reed’s Self-Transcendence Scale, adapted to Spanish (Pena-Gayo et al., 2018) and based on the middle-range theory of self-transcendence. Another example is Piedmont’s Assessment of Spirituality and Religious Sentiments (ASPIRES) scale, which assesses spirituality through two dimensions: religious sentiments and spiritual transcendence. This scale is based on a psychological theory incorporating spirituality as a sixth factor within the five-factor model of personality (Simkin, 2017).

Spirituality has also been used as a dimension for assessing other phenomena essential to people’s well-being. For example, spiritual well-being is a factor in the Meaning in Life Questionnaire (Steger et al., 2006) used in clinical practice and research in palliative care (Schiappacasse Cocio & González Soto, 2016). Due to its abstract, multifaceted nature, spirituality poses challenges for its accurate, reliable measurement, making it essential to know the psychometric properties of the instruments designed and validated in the past ten years to measure this phenomenon. This review will enable us to identify the emerging concepts and definitions, the number of scales developed, the language, populations and cultures in which they have been validated, as well as the level of validity and reliability they present. It is therefore crucial to know what types of validation are most commonly used with these measurement instruments.

This scoping review seeks to contribute to clinical practice and health research by providing an exhaustive matrix that incorporates key elements for selecting the instruments to measure spirituality. This matrix would provide useful evidence for the decision-making of those who wish to use these instruments in both research and clinical practice in this field. Our objective was therefore to summarize the evidence in the literature on the instruments available to assess spirituality in various patient groups and to evaluate the contents and psychometric properties of these instruments.

METHOD

Study design

The following research is a scoping literature review, based on the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR; Tricco et al., 2018). This review was conducted in five stages: 1) problem identification, based on a research question or guiding search question; 2) literature search in databases; 3) data evaluation; 4) data analysis, and 5) presentation of results.

Problem identification

According to the stated objective, the following guiding question was suggested: What scales or instruments for assessing spirituality have been published in the literature in the past ten years with validity and reliability testing?

Literature search

A search of PubMed, Virtual Health Library (VHL), Elsevier, Springer, Scopus, and Google Scholar databases was conducted between January and March 2023. The DeCS/MeSH Health Science Descriptors “espiritualidad” AND (“estudios de validación” OR “psicometría”) were used in Spanish and “spirituality” AND (“validation study” OR “psychometrics”) in English.

Original research articles exploring the design, translation, adaptation and/or validation of instruments related to spirituality, published in Spanish or English between January 2013 and March 2023, and responding to the guiding question were included in the review process. Published articles that did provide a detailed description of the methodological process of designing, translating, adapting, and/or validating the instruments or the different types of validity (content, construct, criterion, convergent, discriminant) were excluded, as well as letters to the editor, conference abstracts, book chapters, and literature reviews.

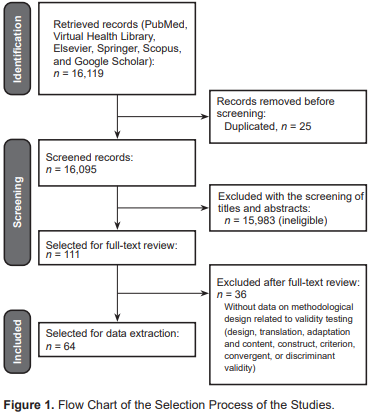

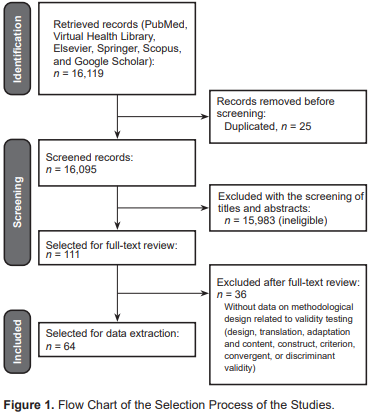

Searching the databases using the descriptors yielded 16,119 studies. A total of 15,983 of these were then excluded after reading the title and abstract because they failed to meet the selection criteria, and 25 because they were duplicates. Afterwards, the full texts of 111 articles were read, and 36 studies were excluded because they failed to specify the methodological design related to validity testing (design, translation, adaptation and content, construct, criterion, convergent, or discriminant validity). Lastly, 64 studies were included in the scoping review, and eight were excluded for containing incomplete information on validity and reliability statistics. The entire selection process is presented in Figure 1.

view

Data evaluation

Methodological quality was first assessed separately by the researchers and then by consensus. We began by reading the full text of the studies and then proceeded to rate the methodological quality individually using the COSMIN Risk of Bias checklist (Mokkink et al., 2018). The COSMIN checklist assesses methodological rigor and risk of bias according to the type of validity tested by the survey researchers. The appropriate boxes are filled in by study type to determine the overall quality of the study. The lowest score of each evaluated standard is used, using the “worst score counts” principle.

Data were summarized in a database created by the researchers, detailing the characteristics of the studies: database, authors, name of scale, country of validation, language of validation, language of publication, country of study, population, main concept of instrument, theoretical basis of concept, dimensions of concept or subscales, and validity and reliability. Results were analyzed, evaluated, and interpreted based on the planned objective and guiding search question. The researchers worked together to complete this process. Duplicates were discarded using Mendeley software (Elsevier © 2018).

Data analysis

After the reviewers’ quality assessment and selection of studies, the recommendations of PRISMA-ScR (2018) were followed. The first phase in data analysis was data reduction, which involved synthesizing the information found through an overall classification system. To this end, a matrix was created with the characteristics of the studies: database, authors, name of scale, country of validation, language of validation, language of publication, country of study, population, main concept of instrument, theoretical basis of concept, dimensions of concept or subscales, and validity and reliability.

The next phase of the data analysis was data display, which involved examining the display of the primary information sources to identify patterns, themes, and relationships. This enabled all the derived, defined, and validated constructs assessing spirituality in people to be identified. During the third phase, involving data comparison, the instruments were grouped according to the construct assessed, and some of the results found were compared, as well as the types of validity testing among the instruments. As a result of these two phases, two essential contents or categories were identified that will be presented in the following section: constructs related to spirituality and their measurement scales and the validity and reliability of the instruments or scales for assessing spirituality. During the final phase, we drew and verified conclusions. We then condensed the main elements and arrived at overall conclusions that are useful for both practice and research.

RESULTS

General Description of Studies

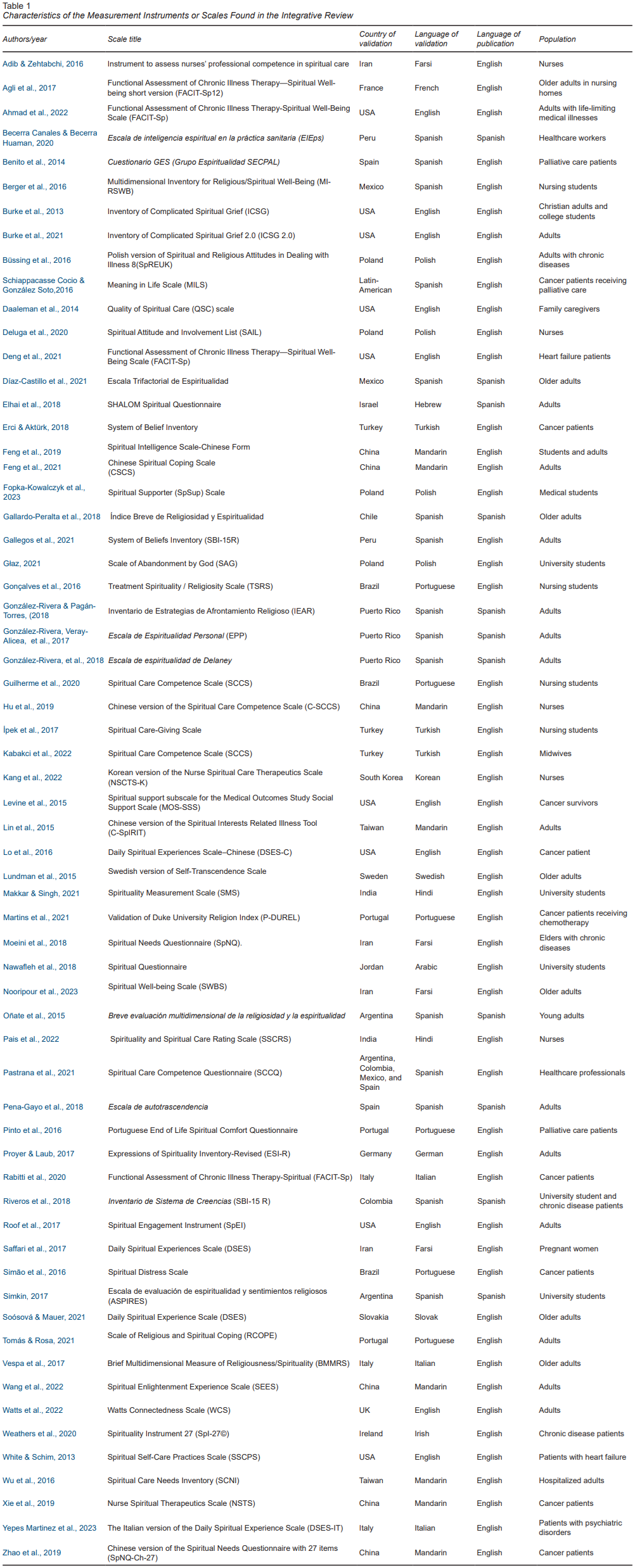

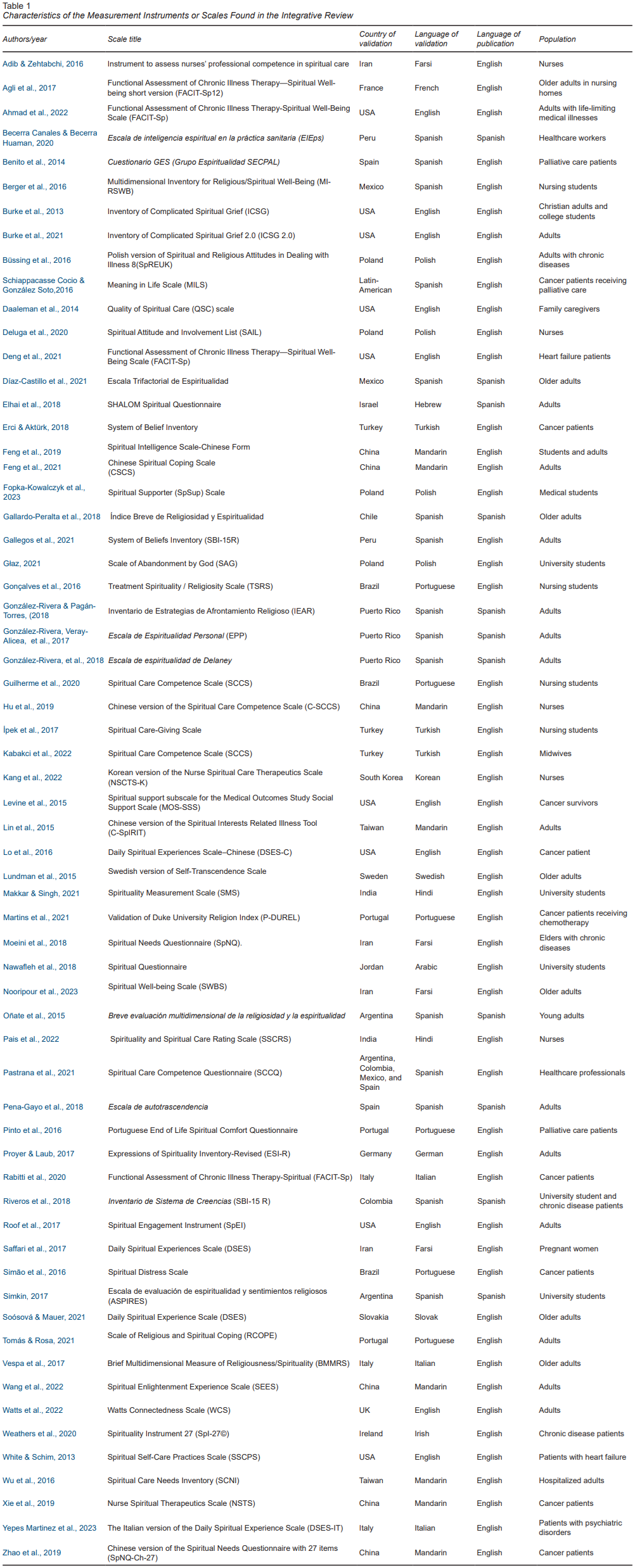

Table 1 describes the characteristics of the measurement instruments or scales reviewed. Validated measurement instruments were mostly found in Asian and Middle Eastern countries (31%, n = 20), such as China, Iran, India, Taiwan, Turkey, Israel, Jordan, and South Korea, and European ones (28%, n = 18), such as Poland, Italy, Portugal, Germany, Slovakia, Spain, France, Ireland, the United Kingdom, and Sweden. Twenty percent of the instruments (n = 13) were validated in South and Central American countries such as Brazil, Argentina, Chile, Colombia, Peru, and Puerto Rico, and 17% (n = 11) in North American countries, mainly the United States and Mexico. Only two multicenter studies were identified (4%). Regarding the language of publication, 83% (n = 53) of the articles reviewed were published in English and 17% (n = 11) in Spanish.

view

Constructs Related to Spirituality and its Measurement Scales

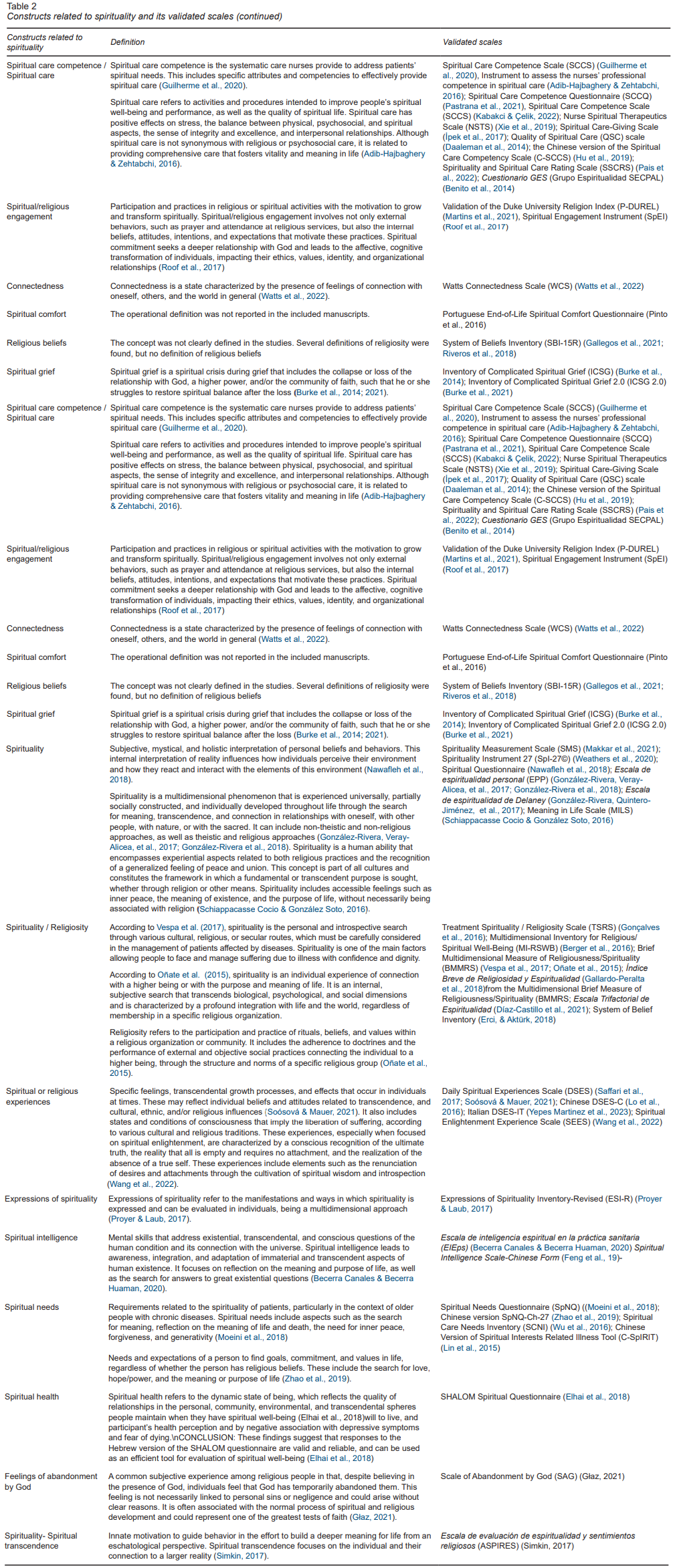

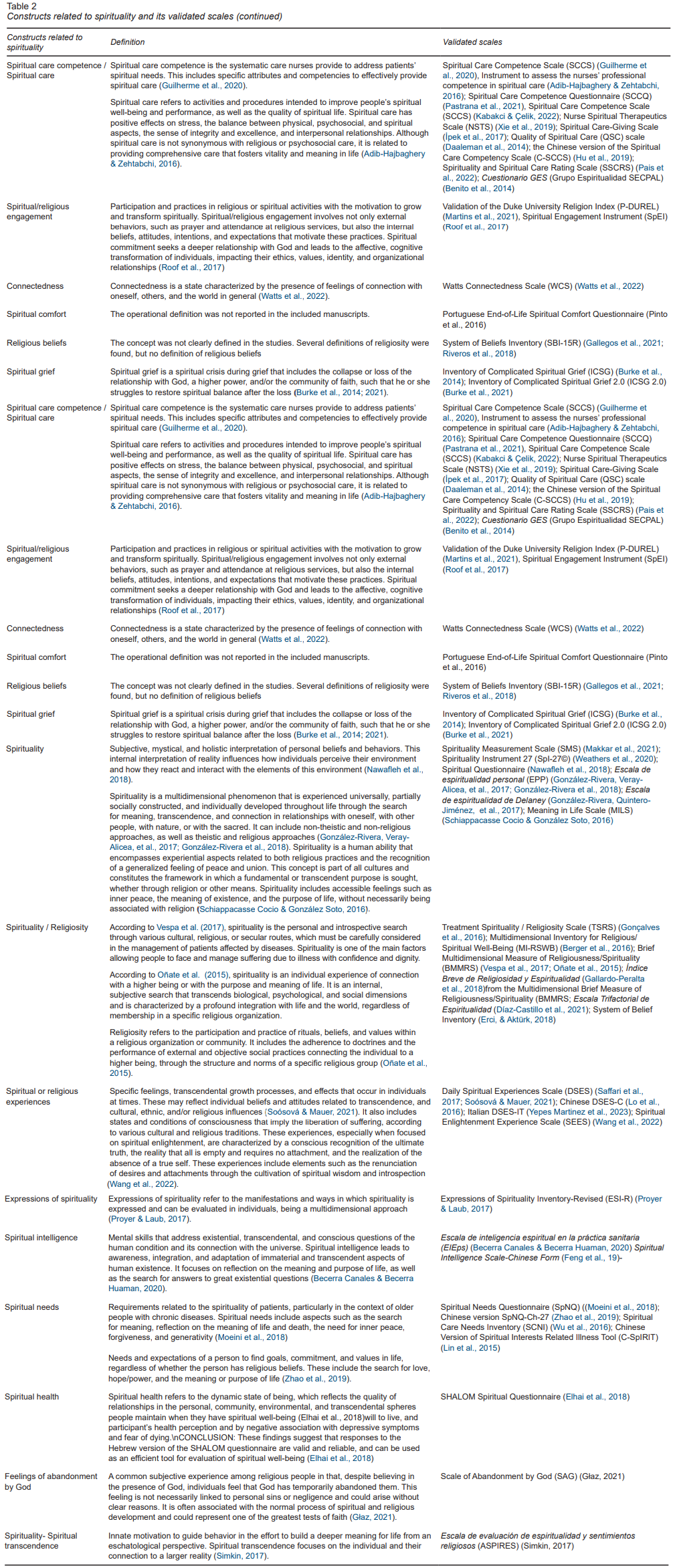

In the present review, 22 conceptual constructs were identified that assess spirituality or some aspect of the latter. These constructs are shown in Table 2. The construct related to spirituality with the largest number of instruments is spiritual care or spiritual care competence, with a total of ten instruments. In general, these scales assess the level of spiritual care or the ability of nurses or other healthcare professionals to provide spiritual care (Adib-Hajbaghery & Zehtabchi, 2016; Benito et al., 2014; Daaleman et al., 2014; Guilherme et al., 2020; Hu et al., 2019; İpek Çoban et al., 2017; Kabakci et al., 2022; Pais et al., 2022; Pastrana et al., 2021; Xie et al., 2019). According to the operational definitions and constructs of these instruments, spiritual care competence is defined as the ability of nurses or health professionals to identify spiritual needs and to plan and implement care plans, activities or interventions that enhance the spiritual dimension of the subject of care (Adib-Hajbaghery & Zehtabchi, 2016; Benito et al., 2014; Daaleman et al., 2014; Guilherme et al., 2020; Hu et al., 2019; İpek Çoban et al., 2017; Kabakci et al., 2022; Pais et al., 2022; Pastrana et al., 2021; Wang et al., 2022; Xie et al., 2019).

view

Another construct with the largest number of instruments found was spirituality from a theocentric perspective (spirituality/religiosity), with eight instruments (Berger et al., 2016; Erci & Aktürk, 2018; Gallardo-Peralta et al., 2018; Gonçalves et al., 2016; Oñate et al., 2015; Simkin, 2017; Vespa et al., 2017). These scales are striking because they include dimensions such as the connection to God or a higher power and transcendental phenomena such as death (Berger et al., 2016; Díaz-Castillo et al., 2021; Gallardo-Peralta et al., 2018; Gonçalves et al., 2016; Vespa et al., 2017). Items in these dimensions address the most common religious practices, such as prayer, meditation, fasting, and the reading of sacred books, and would be the empirical indicators of the connection with God.

Some instruments assess spirituality as a broad, holistic, multi-dimensional concept. Seven measurement instruments were found that assess spirituality from multiple perspectives and had been validated in different populations. One of the most outstanding features of these instruments is that they have subscales assessing three or more dimensions of spirituality, such as intrapersonal, extrapersonal, and transpersonal connections (González-Rivera & Pagán-Torres, 2018; González-Rivera, Quintero-Jiménez et al., 2017; González-Rivera, Veray-Alicea, et al., 2017; Makkar & Singh, 2021; Nawafleh et al., 2018; Schiappacasse Cocio & González Soto, 2016; Weathers et al., 2020; González-Rivera, et al., 2018).

Spirituality as a holistic dimension has conceptually abstract dimensions, such as meaning (Deluga et al., 2020; González-Rivera & Pagán-Torres, 2018) and self-awareness (Weathers et al., 2020), in some of the instruments reviewed. Spiritual needs are another construct identified (Lin et al., 2015; Moeini et al., 2018; Wu et al., 2016; Zhao et al., 2019). These instruments are designed for people who require spiritual care. Although identifying spiritual needs can be extremely useful, this review did not identify any scales available in Spanish or validated in Spanish-speaking countries that addressed spiritual needs.

The definitions provided in the instruments (Lin et al., 2015; Moeini et al., 2018; Wu et al., 2016; Zhao et al., 2019) suggest that spiritual needs are what people must satisfy to fully develop spirituality or any of its dimensions.

The spiritual and religious experiences construct (Lo et al., 2016; Saffari et al., 2017; Soósová & Mauer, 2021; Wang et al., 2022; Yepes Martinez et al., 2023) assesses spirituality and religiosity from multiple perspectives, including intrapersonal aspects such as meaning, peace, and faith (Saffari et al., 2017), religiosity (Lo et al., 2016; Soósová & Mauer, 2021; Yepes Martinez et al., 2023) and attention to spiritual needs (Wang et al., 2022; Yepes Martinez et al., 2023).

Other constructs assessing spirituality found were religious and spiritual coping (Feng et al., 2019; González-Rivera & Pagán-Torres, 2018; Tomás & Rosa, 2021), spiritual and religious attitudes (Büssing et al., 2016; Deluga et al., 2020), self-transcendence (Lundman et al., 2015; Pena-Gayo et al., 2018), spiritual distress (Simão et al., 2016), spiritual self-care (White & Schim, 2013), spiritual support (Fopka-Kowalczyk et al., 2023; Levine et al., 2015), spiritual well-being (Agli et al., 2017; Ahmad et al., 2022; Deng et al., 2021; Nooripour et al., 2023; Rabitti et al., 2020), spiritual and/or religious engagement (Martins et al., 2021; Roof et al., 2017), connectedness (Watts et al., 2022), spiritual comfort (Pinto et al., 2016), religious beliefs (Gallegos et al., 2021; Riveros et al., 2018), spiritual grief (Burke et al., 2013, 2021), spiritual and/or religious expressions (Proyer & Laub, 2017), spiritual intelligence (Becerra Canales & Becerra Huaman, 2020; Feng et al., 2019), feelings of abandonment by God (Głaz, 2021), and spiritual transcendence (Simkin, 2017).

Of the 22 concepts related to spirituality, four were found to lack clear operational definitions in the psychometric studies reviewed. Most of these studies presented multiple theoretical definitions of spirituality and religiosity, highlighting both the differences between constructs and their shared defining characteristics. However, many of these studies lacked a precise definition of the phenomenon they aimed to measure using a solid theoretical or empirical reference, revealing a possible conceptual confusion between the construct of spirituality and emerging concepts such as spiritual and religious attitudes, spiritual support, spiritual comfort and religious beliefs.

We identified three concepts that might seem similar: spiritual distress, spiritual pain, and feelings of abandonment by God. While the definition of these concepts suggests that people may experience a loss in their relationship with God or a transpersonal disconnection at some point, they are distinguished by their conceptual boundaries. Spiritual pain is linked to grief, whereas spiritual distress focuses on an internal conflict related to beliefs and values. Conversely, feelings of abandonment by God refer to the perception of a temporary separation from God for no clear reason. However, this feeling is part of the process of spiritual growth.

Although most of the concepts are understandable, most of the definitions found in psychometric studies are not consistent with the dimensions of the instruments used. Moreover, in many studies involving the translation and cultural adaptation of instruments to measure spirituality, the researcher’s original definition of the instrument was not clarified, making it difficult to conduct an exhaustive analysis of the validity of the construct in these contexts.

Validity and Reliability of the Instruments or scales for the Assessment of Spirituality

The populations in which the instruments were validated were primarily adults of all ages (Burke et al., 2021; Elhai et al., 2018; Feng et al., 2019; Gallegos et al., 2021; González-Rivera & Pagán-Torres, 2018; González-Rivera, Quintero-Jiménez, et al., 2017; González-Rivera, Veray-Alicea, et al., 2017; Lin et al., 2015; Lundman et al., 2015; Oñate et al., 2015; Pena-Gayo et al., 2018; Proyer & Laub, 2017; Roof et al., 2017; Tomás & Rosa, 2021; Wang et al., 2022; Watts et al., 2022; Wu et al., 2016), healthcare professionals (Becerra-Partida et al., 2019; Pastrana et al., 2021) such as nurses (Adib-Hajbaghery & Zehtabchi, 2016; Deluga et al., 2020; Hu et al., 2019; Kang et al., 2022; Pais et al., 2022), university students (Berger et al., 2016; Głaz, 2021; González-Rivera & Pagán-Torres, 2018; Guilherme et al., 2020; Makkar & Singh, 2021; Nawafleh et al., 2018; Riveros et al., 2018; Simkin et al., 2017) , nursing students (Fopka-Kowalczyk et al., 2023; Gonçalves et al., 2016; Guilherme et al., 2020; İpek Çoban et al., 2017), and people diagnosed with cancer (Erci & Aktürk, 2018; Lo et al., 2016; Martins et al., 2021; Pinto et al., 2016; Schiappacasse Cocio & González Soto, 2016; Simão et al., 2016; Xie et al., 2019; Zhao et al., 2021).

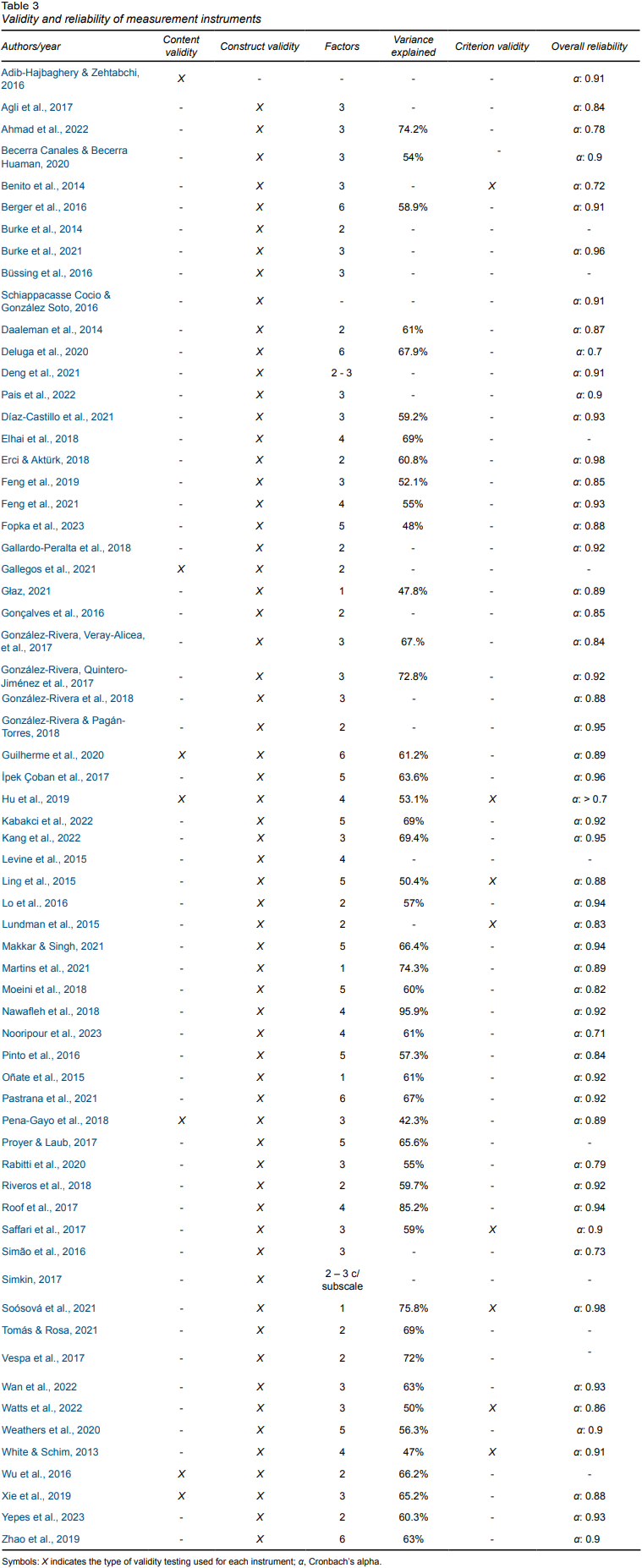

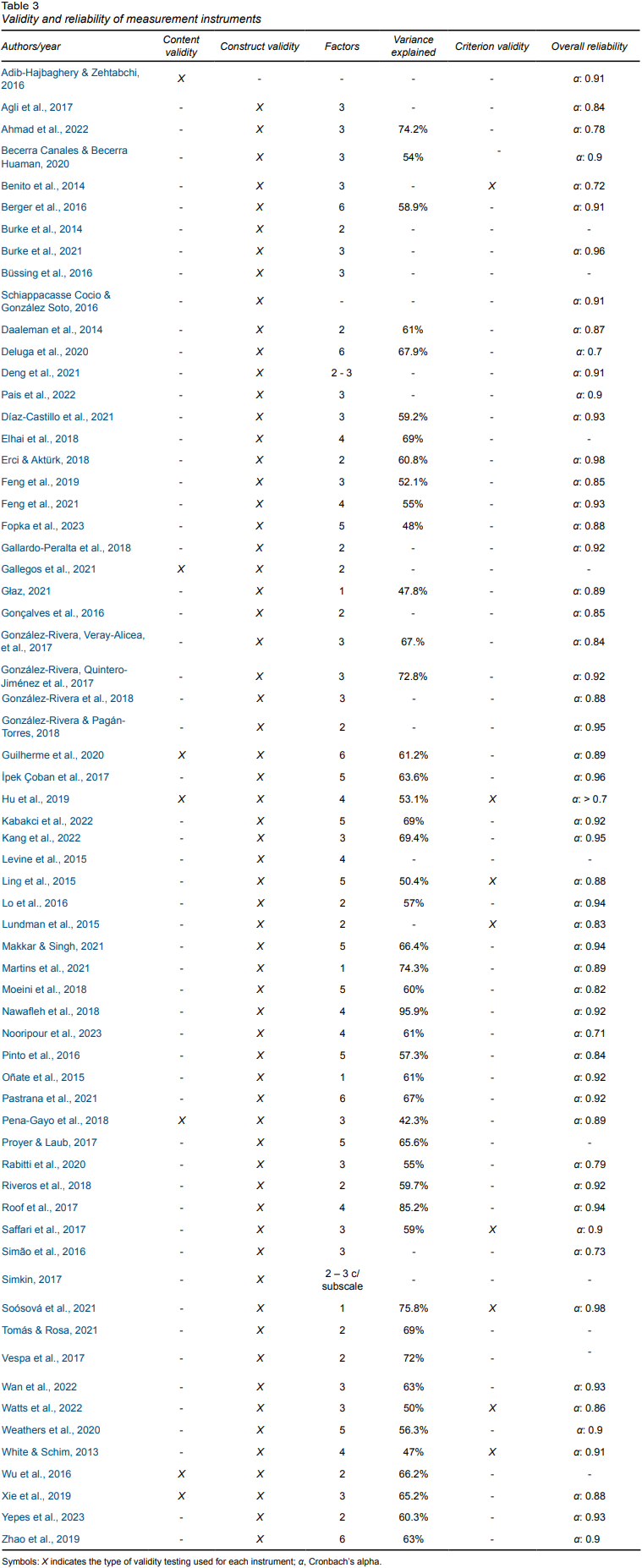

Of all the studies reviewed, only 11% (n = 7) measured content validity with a panel of experts (Adib-Hajbaghery & Zehtabchi, 2016; Gallegos et al., 2021; Guilherme et al., 2020; Hu et al., 2019; Wu et al., 2013; Xie et al., 2019), usually comprising nurses, theologians, psychologists, and priests. The number of experts ranged from five to 20.

Ninety-seven per cent of the studies reviewed (n = 61) measured construct validity using exploratory factor analysis, confirmatory factor analysis, or model fit indices, as shown in Table 3. Convergent construct validity was only measured in one instrument (Schiappacasse Cocio & González Soto, 2016).

view

Among the instruments with construct validity testing, we found an average of three factors, ranging from one to six, with an average of 61% of total explained variance, ranging from 42.3% to 95.9%. Of the instruments, 84.3% (n = 54) reported overall reliability using Cronbach’s alpha, with a range of 0.71 to 0.98.

DISCUSSION AND CONCLUSION

Main results

This review identified 64 research studies assessing spirituality from different theoretical and philosophical points of view and perspectives, including those specific to a particular population. The various constructs that can arise from spirituality or deal with the spiritual dimension of a human being are usually extremely abstract and often difficult to understand due to the nature of the phenomenon (Fuentes, 2018). Some characteristics theorists have identified about spirituality should be highlighted, such as the fact that it is subjective and individual and develops differently in each person (Sarrazin Martínez, 2021).

This level of abstraction of the phenomenon gives it interpretive richness, enabling it to be evaluated from multiple theoretical perspectives. Among the psychometric studies, three approaches were identified in the definitions of spirituality or an emerging concept of this phenomenon. The first is a homocentric approach, where humans connect and relate to their environment, finding purpose or meaning in their lives through these connections. The second is a theocentric approach, in which humans establish a relationship with God, a higher power, or a mystical element, finding fulfillment and their life’s purpose in it. The third is a mixed vision, which does not separate the different connections humans establish. All these approaches enable humans to transcend their lives. These findings were expected given the nature of the phenomenon, since spirituality favors a connection with the variables of the being at an intrapersonal, interpersonal, and transpersonal level (Fuentes, 2018; López-Tarrida et al., 2020), which in turn leads the person to transcend (Reed, 2018, 2021).

Spiritual needs are one of the constructs enabling us to assess spirituality in people who are ill. Identifying spiritual needs can be helpful in healthcare practice. It is because it facilitates the identification of challenges in religious or intra- and intrapersonal practices that it can be useful for hospitalized people or those with health problems (Morales-Ramón & Ojeda-Vargas, 2014; Pérez-García, 2016). However, nursing practice would be limited if only spiritual needs of a religious nature were addressed (Morales-Ramón & Ojeda-Vargas, 2014; Muñoz Devesa et al., 2014).

Among the multiple constructs of spirituality, religious practices or rituals and theocentric belief systems are part of the transpersonal dimension of spirituality in believers. Although these two constructs closely related in some ways, they are theoretically quite different (Sarrazin Martínez, 2021). Instruments assessing religiosity as part of spirituality are therefore useful for religious populations.

A total of 54 different instruments assessed spirituality from multiple components, theories, and philosophical perspectives. This could be because spiritual care is becoming increasingly requested at institutions due to the implementation of human caring models in clinical practice (Soto-Rubio et al., 2020). Nurses and other health professionals are therefore becoming more aware and knowledgeable about this phenomenon, as reported by (Sarrazin Martínez, 2021).

However, in several of the instruments found, there is evidence of a lack of conceptual clarity in the constructs assessed, making it difficult to understand the empirical indicators. This can also be observed in the similarity of items found in instruments assessing spirituality from different constructs.

Given the nature of the phenomenon, a lack of conceptual clarity is common in studies conducted since the 1990s. A previous review on spirituality questionnaires, conducted by de Jager Meezenbroek et al. (2012), reported that the items in the questionnaires analyzed were not as clear or appropriate for practice. Therefore, although numerous scales, inventories, and instruments exist to measure spirituality, exploring, assessing, and approaching spirituality in clinical practice is complex (López-Tarrida et al., 2020), especially when the constructs in the instruments are unclear.

Waltz et al. (2017) suggest that the first step a researcher should take when designing instruments, is conceptual operationalization, in which attributes, characteristics and dimensions are defined to distinguish the concept being assessed from others that could be considered synonyms. Conceptual inaccuracy has been one of the most common flaws in instruments assessing attributes of spirituality. This could be due to the lack of fit between the dimensions of the instruments and the conceptual definition of the phenomenon that is to be measured. It was clear from most psychometric studies that the conceptual definition was not consistent with the instrument or its dimensions. Although a conceptual definition of spirituality was given in the introduction section of many of the studies included in this review, the dimensions of the validated instrument were not known until the material and methods section. The defining characteristics enable concepts to be differentiated, thereby establishing a conceptual delimitation. These elements are known as dimensions or factors, and items are grouped according to these defining characteristics, dimensions, or factors, thereby measuring the concept intended to be evaluated (Waltz et al., 2017). The lack of a clear link between the conceptual definition and the dimensions of the instrument can therefore limit accuracy in measuring the phenomenon.

In this review, three types of validity (content, construct, and criterion) were measured for the Spiritual Caregiving Scale (Hu et al., 2019), and only seven studies measured content validity. Content validity is a logical judgment attempting to determine whether items reflect the content domain being measured by assessing clarity, coherence, relevance, and (Urrutia Egaña et al., 2014).

Construct validity was the most frequently reported aspect in the measurement instruments reviewed. A total of 73% of the studies used Bartlett’s test of sphericity and the Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin (KMO) measure to verify sampling adequacy for factor analysis. The KMO test shows the degree to which each variable can be predicted by the other variables. This statistic must be calculated before running the correlation matrices for factor analysis, and the criterion that KMO must be equal to or greater than 0.8 must be met (Pizarro Romero & Martínez Mora, 2020).

Bartlett’s test of sphericity indicates whether a correlation matrix is suitable for factor analysis, for which it must be < 0.5 (López-Aguado & Gutiérrez-Provecho, 2019). Factor analysis can then be performed. The grouping of items into factors in the pilot test confirms the concept or construct being measured by empirically dividing these groupings into dimensions (Lloret-Segura et al., 2014). To ensure accurate assessment, it is essential to clearly define the unique qualities and characteristics that differentiate the concept from others.

Certain aspects must be considered for an adequate interpretation of our results. Although our systematic search to identify the articles included in this review was not restricted by geographic region or language of publication, we cannot guarantee that we have managed to retrieve all the manuscripts on the psychometric properties of instruments evaluated spirituality, which is a limitation of this type of studies.

Despite this limitation, advantages of the present review include the fact that we searched for studies in six different electronic databases, enabling us to summarize the available evidence on the topic of interest from a larger number of studies than previous reviews. Moreover, unlike other reviews, we included information on instruments to assess spirituality among different population groups. Furthermore, researchers read and evaluated the articles to ensure an appropriate and scientifically rigorous selection, and the evaluation was conducted in phases.

In conclusion, since spirituality can be measured from multiple perspectives, concepts, and theoretical points of reference, numerous constructs have been created. Although the level of conceptual abstraction of this phenomenon provides a richness of interpretation, in practice this can cause confusion.

The need for greater clarity in certain constructs in spirituality scales is evinced by the similarity of items across instruments. There is often a lack of clarity between the conceptual operationalization and wording of the categories and empirical indicators.

Most of the studies included in this review only measured the construct validity of instruments to assess spirituality, ignoring content and criterion validity. The absence of holistic validation could restrict the precision and applicability of the measurements made, thus limiting their usefulness in various research contexts or practical applications.

The reliability of the measurement instruments analyzed in this review ranged from 0.7 to 0.98. This wide range of reliability indicates sharp differences in the consistency and stability of the measurements obtained through these instruments. Despite the variability, it is important to note that most instruments demonstrate levels of reliability that can be considered acceptable in terms of internal consistency and reproducibility of results. However, it should be noted that reliability alone does not guarantee the validity of measurements, as precision and consistency may not necessarily determine the accuracy of what is being measured.

Funding

We would like to the Mexican National Council of Humanities, Science, and Technology (CONAHCYT) for the scholarship granted to KJAR (967259.) during his doctoral training.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare they have no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

Adib-Hajbaghery, M., & Zehtabchi, S. (2016). Developing and Validating an Instrument to Assess the Nurses’ Professional Competence in Spiritual Care. Journal of Nursing Measurement, 24(1), 15-27. https://doi.org/10.1891/1061-3749.24.1.15

Agli, O., Bailly, N., & Ferrand, C. (2017). Validation of the Functional Assessment of Chronic Illness Therapy—Spiritual Well-being (FACIT-Sp12) on French Old People. Journal of Religion and Health, 56(2), 464-476. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10943-016-0220-0

Ahmad, N., Sinaii, N., Panahi, S., Bagereka, P., Serna-Tamayo, C., Shnayder, S., Ameli, R., & Berger, A. (2022). The FACIT-Sp spiritual wellbeing scale: a factor analysis in patients with severe and/or life-limiting medical illnesses. Annals of Palliative Medicine, 11(12), 3663-3673. https://doi.org/10.21037/apm-22-692

Becerra Canales, B., & Becerra Huaman, D. (2020). Diseño y validación de la escala de Inteligencia Espiritual en la práctica sanitaria, Ica-Perú. Enfermería Global, 19(4), 349-378. https://doi.org/10.6018/eglobal.417371

Becerra-Partida, E. N., Millán, R. M., & Arias, D. R. R. (2019). Depresión en pacientes con diabetes mellitus tipo 2 del programa DiabetIMSS en Guadalajara, Jalisco, México. Revista CONAMED, 24(4), 174–178. http://www.conamed.gob.mx/gobmx/revista/pdf/vol_23_2018/COMPLETO_4.pdf

Benito, E., Oliver, A., Galiana, L., Barreto, P., Pascual, A., Gomis, C., & Barbero, J. (2014). Development and Validation of a New Tool for the Assessment and Spiritual Care of Palliative Care Patients. Journal of Pain and Symptom Management, 47(6), 1008-1018.e1. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2013.06.018

Berger, D., Fink, A., Perez Gomez, M. M., Lewis, A., & Unterrainer, H. (2016). The Validation of a Spanish Version of the Multidimensional Inventory of Religious/Spiritual Well-Being in Mexican College Students. The Spanish Journal of Psychology, 19, https://doi.org/10.1017/sjp.2016.9

Burke, L. A., Crunk, A. E., Neimeyer, R. A., & Bai, H. (2021). Inventory of Complicated Spiritual Grief 2.0 (ICSG 2.0): Validation of a revised measure of spiritual distress in bereavement. Death Studies, 45(4), 249-265. https://doi.org/10.1080/07481187.2019.1627031

Burke, L. A., Neimeyer, R. A., Holland, J. M., Dennard, S., Oliver, L., & Shear, M. K. (2013). Inventory of Complicated Spiritual Grief: Development and Validation of a New Measure. Death Studies, 38(4), 239–250. https://doi.org/10.1080/07481187.2013.810098

Büssing, A., Franczak, K., & Surzykiewicz, J. (2016). Spiritual and Religious Attitudes in Dealing with Illness in Polish Patients with Chronic Diseases: Validation of the Polish Version of the SpREUK Questionnaire. Journal of Religion and Health, 55(1), 67–84. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10943-014-9967-3

Caccia, P., & Elgier, M. (2020). Resiliencia y satisfacción con la vida en adolescentes según nivel de espiritualidad. PSOCIAL; 6(2), 62–70. https://publicaciones.sociales.uba.ar/index.php/psicologiasocial/article/view/5975

Daaleman, T. P., Reed, D., Cohen, L. W., & Zimmerman, S. (2014). Development and Preliminary Testing of the Quality of Spiritual Care Scale. Journal of Pain and Symptom Management, 47(4), 793-800. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2013.06.004

de Diego-Cordero, R., Suárez-Reina, P., Badanta, B., Lucchetti, G., & Vega-Escaño, J. (2022). The efficacy of religious and spiritual interventions in nursing care to promote mental, physical and spiritual health: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Applied Nursing Research, 67, 151618. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apnr.2022.151618

de Jager Meezenbroek, E., Garssen, B., van den Berg, M., van Dierendonck, D., Visser, A., & Schaufeli, W. B. (2012). Measuring Spirituality as a Universal Human Experience: A Review of Spirituality Questionnaires. Journal of Religion and Health, 51(2), 336-354. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10943-010-9376-1

Deluga, A., Dobrowolska, B., Jurek, K., Ślusarska, B., Nowicki, G., & Palese, A. (2020). Nurses’ spiritual attitudes and involvement—Validation of the Polish version of the Spiritual Attitude and Involvement List. PLOS ONE, 15(9), e0239068. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0239068

Deng, L. R., Masters, K. S., Schmiege, S. J., Hess, E., & Bekelman, D. B. (2021). Two Factor Structures Possible for the FACIT-Sp in Patients With Heart Failure. Journal of Pain and Symptom Management, 62(5), 1034-1040. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2021.05.009

Díaz-Castillo, R., Montero-López Lena, M., González-Escobar, S., & González-Arratia López Fuente, N. I. (2021). Desarrollo y validación de la Escala Trifactorial de Espiritualidad en personas adultas mayores mexicanas. Neurama, 8(1), 39–52. https://www.neurama.es/articulos/15/articulo4.pdf

Elhai, N., Carmel, S., O’Rourke, N., & Bachner, Y. G. (2018). Translation and validation of the Hebrew version of the SHALOM Spiritual questionnaire. Aging & Mental Health, 22(1), 46–52. https://doi.org/10.1080/13607863.2016.1222350

Epstein, J., Santo, R. M., & Guillemin, F. (2015). A review of guidelines for cross-cultural adaptation of questionnaires could not bring out a consensus. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology, 68(4), 435-441. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclinepi.2014.11.021

Erci, B., & Aktürk, Ü. (2018). The System of Belief Inventory: A Validation Study in Turkish Cancer Patients. Journal of religion and health, 57(4), 1237-1245. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10943-017-0406-0

Feng, J., Li, Y., Sun, Y., Wang, L., Qi, W., Wang, K. T., & Xue, Y. (2021). The Chinese Spiritual Coping Scale: Development and Initial Psychometric Evaluation. Journal of religion and health, 60(1), 458–474. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10943-019-00970-z

Feng, M., Xiong, X.-y., & Li, J.-j. (2019). Spiritual Intelligence Scale--Chinese form: Construction and initial validation. Current Psychology: A Journal for Diverse Perspectives on Diverse Psychological Issues, 38(5), 1318–1327. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-017-9678-5

Fopka-Kowalczyk, M., Best, M., & Krajnik, M. (2023). The Spiritual Supporter Scale as a New Tool for Assessing Spiritual Care Competencies in Professionals: Design, Validation, and Psychometric Evaluation. Journal of religion and health, 62(3), 2081–2111. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10943-022-01608-3

Fuentes, L. del C. (2018). La Religiosidad y la Espiritualidad ¿Son conceptos teóricos independientes? Revista de Psicología, 14(28), 109-119. https://erevistas.uca.edu.ar/index.php/RPSI/article/view/1742

Gallardo-Peralta, L. P., Cuadra-Peralta, A., & Veloso-Besio, C. (2018). Validación de un Índice Breve de Religiosidad y Espiritualidad en personas mayores. Revista de Psicología, 27(1), 1. https://doi.org/10.5354/0719-0581.2018.50736

Gallegos, W. L. A., Loayza, A. E., Rivera, R., & Cohello, A. L. N. (2021). Modified and Validated Version of the System of Beliefs Inventory (SBI-15R) in a Sample of Inhabitants from Arequipa City (Peru). International Journal of Latin American Religions, 5(2), 501-518. https://doi.org/10.1007/s41603-021-00139-1

González-Rivera, J. A., & Pagán-Torres, O. M. (2018). Desarrollo y Validación de un instrumento para medir Estrategias de Afrontamiento Religioso. Revista Evaluar, 18(1), 70-86. https://doi.org/10.35670/1667-4545.v18.n1.19771

González-Rivera, J. A., Quintero-Jiménez, N., Veray-Alicea, J., & Rosario-Rodríguez, A. (2017). Adaptación y validación de la escala de espiritualidad de delaney en una muestra de adultos puertorriqueños. Revista Electrónica de Psicología Iztacala, 20(1). https://www.revistas.unam.mx/index.php/repi/article/view/58935

González-Rivera, J. A., Veray-Alicea, J., & Rosario-Rodríguez, A. (2017). Desarrollo, validación y descripción teórica de la escala de espiritualidad personal en una muestra de adultos en Puerto Rico. Revista Puertorriqueña de Psicología, 28(2), 388-404.

González-Rivera, J., Rosario-Rodríguez, A., & Pagán-Torres, O. (2018). Confirmatory Factorial Analysis of the Personal Spirituality Scale in Puerto Ricans Adults Interacciones. Interacciones, 4(3), 153-162. https://doi.org/10.24016/2018.v4n3.101

Gonçalves, A. M. D. S., Santos, M. A. D., Chaves, E. D. C. L., & Pillon, S. C. (2016). Adaptação transcultural e validação da versão brasileira da Treatment Spirituality / Religiosity Scale. Revista Brasileira de Enfermagem, 69(2), 235-241. https://doi.org/10.1590/0034-7167.2016690205i

Guilherme, C., Fulquini, F., Ribeiro, V., Gadioli, B., Eduardo, A., Caldeira, S., & Carvalho, E. (2020). Validity evidenceofthe spiritual care competence scale for brazilian undergraduate nursing students. Reme: Revista Mineira de Enfermagem, 24(1), e-1343. https://doi.org/10.5935/1415.2762.20200080

Głaz, S. (2021). Psychological Analysis of Religiosity and Spirituality: Construction of the Scale of Abandonment by God (SAG). Journal of Religion and Health, 60(5), 3545–3561. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10943-021-01197-7

Herdman, M., Fox-Rushby, J., & Badia, X. (1998). A model of equivalence in the cultural adaptation of HRQoL instruments: the universalist approach. Quality of life research : an international journal of quality of life aspects of treatment, care and rehabilitation, 7(4), 323-335. https://doi.org/10.1023/a:1024985930536

Hu, Y., Tiew, L. H., & Li, F. (2019). Psychometric properties of the Chinese version of the spiritual care-giving scale (C-SCGS) in nursing practice. BMC Medical Research Methodology, 19(1), 21. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12874-019-0662-7

İpek Çoban, G., Şirin, M., & Yurttaş, A. (2017). Reliability and Validity of the Spiritual Care-Giving Scale in a Turkish Population. Journal of Religion and Health, 56(1), 63-73. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10943-015-0086-6

Kabakci, E. N., & Çelik, N. (2022). Adaptation into Turkish and evaluation of the psychometric properties of the Spiritual Care Competence Scale. Central European Journal of Nursing and Midwifery, 13(2), 648-656. https://doi.org/10.15452/cejnm.2022.13.0001

Kang, K. A., Taylor, E. J., & Chun, J. (2022). Nurse Spiritual Care Therapeutics Scale: Validation Among Nurses Who Care for Patients With Life-Threatening Illnesses in South Korea. Journal of hospice and palliative nursing, https://doi.org/10.1097/NJH.0000000000000895. Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1097/NJH.0000000000000895

Levine, E. G., Vong, S., & Yoo, G. J. (2015). Development and Initial Validation of a Spiritual Support Subscale for the MOS Social Support Survey. Journal of Religion and Health, 54(6), 2355-2366. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10943-015-0005-x

Lin, Y. L., Rau, K. M., Liu, Y. H., Lin, Y. H., Ying, J., & Kao, C. C. (2015). Development and validation of the Chinese Version of Spiritual Interests Related Illness Tool for patients with cancer in Taiwan. European journal of oncology nursing, 19(5), 589-594. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejon.2015.03.005

Lloret-Segura, Susana, Ferreres-Traver, Adoración, Hernández-Baeza, Ana, & Tomás-Marco, Inés. (2014). El Análisis Factorial Exploratorio de los Ítems: una guía práctica, revisada y actualizada. Anales de Psicología, 30(3), 1151-1169. https://dx.doi.org/10.6018/analesps.30.3.199361

Lo, G., Chen, J., Wasser, T., Portenoy, R., & Dhingra, L. (2016). Initial Validation of the Daily Spiritual Experiences Scale in Chinese Immigrants With Cancer Pain. Journal of Pain and Symptom Management, 51(2), 284-291. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2015.10.002

López-Aguado, M., & Gutiérrez-Provecho, L. (2019). Cómo realizar e interpretar un análisis factorial exploratorio utilizando SPSS. REIRE Revista d’Innovaciói Recerca en Educació, 12(2), https://doi.org/10.1344/reire2019.12.227057

López-Tarrida, Á. C, Ruiz-Romero, V., & González-Martín, T. (2020). Cuidando con sentido: la atención de lo espiritual en la práctica clínica desde la perspectiva del profesional. Revista Española de Salud Pública, 94, 202001002. Recuperado en 08 de enero de 2025, de http://scielo.isciii.es/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S1135-57272020000100083&lng=es&tlng=es.

Lundman, B., Årestedt, K., Norberg, A., Norberg, C., Fischer, R. S., & Lövheim, H. (2015). Psychometric Properties of the Swedish Version of the Self-Transcendence Scale Among Very Old People. Journal of Nursing Measurement, 23(1), 96-111. https://doi.org/10.1891/1061-3749.23.1.96

Makkar, S., & Singh, A. K. (2021). Development of a spirituality measurement scale. Current Psychology, 40(3), 1490-1497. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-018-0081-7

Martins, H., Caldeira, S., Domingues, T., Vieira, M., & Koenig, H. (2021). Validation of the Duke University Religion Index (DUREL) in Portuguese Cancer Patients Undergoing Chemoterapy. Journal of Religion and Health, 60(5), 3562-3575. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10943-020-01143-z

Moeini, B., Zamanian, H., Taheri-Kharameh, Z., Ramezani, T., Saati-Asr, M., Hajrahimian, M., & Amini-Tehrani, M. (2018). Translation and Psychometric Testing of the Persian Version of the Spiritual Needs Questionnaire Among Elders With Chronic Diseases. Journal of Pain and Symptom Management, 55(1), 94-100. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2017.08.024

Mokkink, L. B., de Vet, H. C. W., Prinsen, C. A. C., Patrick, D. L., Alonso, J., Bouter, L. M., & Terwee, C. B. (2018). COSMIN Risk of Bias checklist for systematic reviews of Patient-Reported Outcome Measures. Quality of life research, 27(5), 1171-1179. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11136-017-1765-4

Morales Contreras, B. N., & Palencia Sierra, J. J. (2021). Dimensión espiritual en el cuidado enfermero. Enfermería Investiga, 6(2), 51-59. https://doi.org/10.31243/ei.uta.v6i2.1073.2021

Morales-Ramón, F., & Ojeda-Vargas, M. G. (2014). El cuidado espiritual como una oportunidad de cuidado y trascendencia en la atención de enfermería. Salud en Tabasco, 20(3), 94-97.

Muñiz, J., & Fonseca-Pedrero, E. (2019). Diez pasos para la construcción de un test. Psicothema, 1(31), 7-16. https://doi.org/10.7334/psicothema2018.291

Muñoz Devesa, A., Morales Moreno, I., Bermejo Higuera, J. C., & Galán González Serna, J. M. (2014). La Enfermería y los cuidados del sufrimiento espiritual. Index de Enfermería, 23(3), 153-156. https://doi.org/10.4321/s1132-12962014000200008

Nawafleh, H. A., Al Hadid, L. A., Al Momani, M. M., & Al Barmawi, M. (2018). Measuring the psychometric properties of the Arabic version of the spirituality questionnaire among university students in South Jordan. Applied Nursing Research, 39, 115-120. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apnr.2017.11.008

Nooripour, R., Ghanbari, N., Hosseinian, S., Ronzani, T. M., Hussain, A. J., Ilanloo, H., Majd, M. A., Soleimani, E., Saffarieh, M., & Yaghoob, V. (2023). Validation of the Spiritual Well-being Scale (SWBS) and its role in Predicting Hope among Iranian Elderly. Ageing International, 48(2), 593-611. https://doi-org.ugto.idm.oclc.org/10.1007/s12126-022-09492-8

Oñate, M. E., Resett, S., Sanabria, M. E., & MenghI, M. S. (2015). Propiedades psicométricas de la dimensión espiritualidad de la evaluación multidimensional de la religiosidad y la espiritualidad, VII Congreso Internacional de Investigación y Práctica Profesional en Psicología XXII Jornadas de Investigación XI Encuentro de Investigadores en Psicología del MERCOSUR. Facultad de Psicología, Universidad de Buenos Aires. https://www.aacademica.org/000-015/941.pdf

Pagán-Torres, O. M. (2022). Abriendo nuevas puertas: Relevancia clínica de integrar la religión y la espiritualidad en la disciplina de la psicología. Revista Puertorriqueña de Psicología, 33(2), 258–271. https://www.repsasppr.net/index.php/reps/article/view/761

Pais, N., Suresh, S., & DCunha, S. (2022). Spirituality and Spiritual Care in Nursing: Validity of the Spirituality and Spiritual Care Rating Scale in an Indian Context. Journal of Religion and Health, 62, 2131-2143. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10943-022-01634-1

Pastrana, T., Frick, E., Krikorian, A., Ascencio, L., Galeazzi, F., & Büssing, A. (2021). Translation and Validation of the Spanish Version of the Spiritual Care Competence Questionnaire (SCCQ). Journal of Religion and Health, 60(5), 3621-3639. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10943-021-01402-7

Pena-Gayo, A., González-Chordá, V. M., Cervera-Gasch, Á., & Mena-Tudela, D. (2018). Cross-cultural adaptation and validation of Pamela Reed’s Self-Transcendence Scale for the Spanish context. Revista Latino-Americana de Enfermagem, 26, https://doi.org/10.1590/1518-8345.2750.3058

Pérez-García, E. (2016). Enfermería y necesidades espirituales en el paciente con enfermedad en etapa terminal. Enfermería: Cuidados Humanizados, 5(2), 41-45.

Pinto, S. M. O., Berenguer, S. M. A. C., Martins, J. C. A., & Kolcaba, K. (2016). Cultural adaptation and validation of the Portuguese End of Life Spiritual Comfort Questionnaire in Palliative Care patients. Porto Biomedical Journal, 1(4), 147-152. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pbj.2016.08.003

Pizarro Romero, K. P., & Martínez Mora, O. M. (2020). Análisis factorial exploratorio mediante el uso de las medidas de adecuación muestral kmo y esfericidad de bartlett para determinar factores principales. Journal of Science and Research, 5, 903-924. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.4453224

Proyer, R. T., & Laub, N. (2017). The German-Language Version of the Expressions of Spirituality Inventory-Revised: Adaptation and Initial Validation. Current Psychology, 36(1), 1-13. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-015-9379-x

Rabitti, E., Cavuto, S., Iani, L., Ottonelli, S., De Vincenzo, F., & Costantini, M. (2020). The assessment of spiritual well-being in cancer patients with advanced disease: which are its meaningful dimensions? BMC Palliative Care, 19(1), 26. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12904-020-0534-2

Reed, P. G. (2018). Theoryof self-transcendence. In: M. J. Smith, & P. Liehr (Eds.), Middle Range Theory for Nursing, 4th Edition, Vol. 3, pp. 119-145. Springer Publishing Company. https://doi.org/10.1891/9780826159922.0007

Reed, P. G. (2021). Self-Transcendence: Moving from Spiritual Disequilibrium to Well-Being Across the Cancer Trajectory. Seminars in Oncology Nursing, 37(5), 151212. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.soncn.2021.151212

Reed, P. G., & Haugan, G. (2021). Self-Transcendence: A Salutogenic Process for Well-Being. In: G. Haugan & M. Eriksson (Eds.), Health Promotion in Health Care – Vital Theories and Research. Springer. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK585654/

Riveros, F., Bernal, L., Bohórquez, D., Vinaccia, S., & Quiceno, M. (2018). Inventario de sistema de creencias (SBI-15 R) en Colombia: estructura factorial y confiabilidad en población universitaria y en pacientes crónicos. Revista Colombiana de Enfermería, 17, 13-20. https://doi.org/10.18270/rce.v17i13.2103

Roof, R. A., Bocarnea, M. C., & Winston, B. E. (2017). The spiritual engagement instrument. Asian Journal of Business Ethics, 6(2), 215-232. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13520-017-0073-y

Saffari, M., Amini, H., Sheykh-oliya, Z., Pakpour, A. H., & Koenig, H. G. (2017). Validation of the Persian version of the Daily Spiritual Experiences Scale (DSES) in Pregnant Women: A Proper Tool to Assess Spirituality Related to Mental Health. Journal of Religion and Health, 56(6), 2222-2236. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10943-017-0393-1

Sánchez-Villena, A. R., de La Fuente-Figuerola, V., & Ventura-León, J. (2021). Importancia de los estudios semánticos en la adaptación transcultural y validación de instrumentos de medida en Ciencias de la Salud. Enfermería Clínica, 31(2), 126-127. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enfcli.2020.08.002

Sarrazin Martínez, J. P. (2021). La relación entre religión, espiritualidad y salud: una revisión crítica desde las ciencias sociales. Hallazgos, https://doi.org/10.15332/2422409x.5232

Schiappacasse Cocio, G., & González Soto, P. (2016). Validación del test Meaning in Life Scale (MILS) modificado para evaluar la dimensión espiritual en población chilena y latinoamericana con cáncer en cuidados paliativos. Gaceta Mexicana de Oncología, 15(3), 121-127. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gamo.2016.05.004

Simão, T. P., Lopes Chaves, E.deC., Campos de Carvalho, E., Nogueira, D. A., Carvalho, C. C., Ku, Y. L., & Iunes, D. H. (2016). Cultural adaptation and analysis of the psychometric properties of the Brazilian version of the Spiritual Distress Scale. Journal of clinical nursing, 25(1-2), 231-239. https://doi.org/10.1111/jocn.13060

Simkin, H. (2017). Adaptación y Validación al español de la Escala de Evaluación de Espiritualidad y Sentimientos Religiosos (ASPIRES): la trascendencia espiritual en el modelo de los cinco factores. Universitas Psychologica, 16(2). https://doi.org/10.11144/javeriana.upsy16-2.aeee

Soósová, M. S., & Mauer, B. (2021). Psychometrics Properties of the Daily Spiritual Experience Scale in Slovak Elderly. Journal of Religion and Health, 60(1), 563-575. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10943-020-00994-w

Soto-Rubio, A., Perez-Marin, M., Rudilla, D., Galiana, L., Oliver, A., Fombuena, M., & Barreto, P. (2020). Responding to the Spiritual Needs of Palliative Care Patients: A Randomized Controlled Trial to Test the Effectiveness of the Kibo Therapeutic Interview. Frontiers in Psychology, 11. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2020.01979

Steger, M. F., Frazier, P., Oishi, S., & Kaler, M. (2006). The meaning in life questionnaire: Assessing the presence of and search for meaning in life. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 53(1), 80-93. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0167.53.1.80

Tomás, C., & Rosa, P. J. (2021). Validation of a Scale of Religious and Spiritual Coping (RCOPE) for the Portuguese Population. Journal of religion and health, 60(5), 3510-3529. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10943-021-01248-z

Tricco, A. C., Lillie, E., Zarin, W., O’Brien, K. K., Colquhoun, H., Levac, D., Moher, D., Peters, M. D., Horsley, T., Weeks, L., Hempel, S., Akl, E. A., Chang, C., McGowan, J., Stewart, L., Hartling, L., Aldcroft, A., Wilson, M. G., Garritty, C., &Straus, S. E. (2018). PRISMA Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR): Checklist and Explanation. Annals of Internal Medicine, 169(7), 467-473. https://doi.org/10.7326/m18-0850

Urrutia Egaña, M., Barrios Araya, S., Gutiérrez Núñez, M., & Mayorga Camus, M. (2014). Métodos óptimos para determinar validez de contenido. Educación Médica Superior, 28(3), 547-558. https://ems.sld.cu/index.php/ems/article/view/301

Vespa, A., Giulietti, M. V., Spatuzzi, R., Fabbietti, P., Meloni, C., Gattafoni, P., & Ottaviani, M. (2017). Validation of Brief Multidimensional Spirituality/Religiousness Inventory (BMMRS) in Italian Adult Participants and in Participants with Medical Diseases. Journal of Religion and Health, 56(3), 907-915. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10943-016-0285-9

Waltz, C., Strickland, O., & Lenz, E. (2017). Measurement in Nursing and Health Research (5th ed.). Springer Publishing Company, New York. https://www.springerpub.com/measurement-in-nursing-and-health-research-9780826170613.html

Wang, Q., Zhou, X., & Ng, S. (2022). The experiences of spiritual enlightenment: A mixed-method study of the development of a Spiritual Enlightenment Experience Scale. Archive for the Psychology of Religion, 44(3), 175-201. https://doi.org/10.1177/00846724221121686

Watts, R., Kettner, H., Geerts, D., Gandy, S., Kartner, L., Mertens, L., Timmermann, C., Nour, M. M., Kaelen, M., Nutt, D., Carhart-Harris, R., & Roseman, L. (2022). The Watts Connectedness Scale: a new scale for measuring a sense of connectedness to self, others, and world. Psychopharmacology, 239(11), 3461-3483. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00213-022-06187-5

Weathers, E., Coffey, A., McSherry, W., & McCarthy, G. (2020). Development and validation of the Spirituality Instrument-27© (SpI-27©) in individuals with chronic illness. Applied Nursing Research, 56, 151331. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apnr.2020.151331

White, M. L., & Schim, S. M. (2013). Development of a Spiritual Self-Care Practice Scale. Journal of Nursing Measurement, 21(3), 450-462. https://doi.org/10.1891/1061-3749.21.3.450

Wu, H., Bertrand, K. A., Choi, A. L., Hu, F. B., Laden, F., Grandjean, P., & Sun, Q. (2013). Persistent Organic Pollutants and Type 2 Diabetes: A Prospective Analysis in the Nurses’ Health Study and Meta-analysis. Environmental Health Perspectives, 121(2), 153-161. https://doi.org/10.1289/ehp.1205248

Wu, L., Koo, M., Liao, Y.-C., Chen, Y.-M., & Yeh, D.-C. (2016). Development and Validation of the Spiritual Care Needs Inventory for Acute Care Hospital Patients in Taiwan. Clinical Nursing Research, 25(6), 590-606. https://doi.org/10.1177/1054773815579609

Xie, H., Taylor, E. J., Li, M., Wang, Y., & Liang, T. (2019). Nurse Spiritual Therapeutics Scale: Psychometric evaluation among cancer patients. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 28(5-6), 939-946. https://doi.org/10.1111/jocn.14711

Yepes Martinez, M. V., Rossi, R., Ciani, M., & Ferrari, C. (2023). Validation of the Italian Version of the Daily Spiritual Experience Scale Among Psychiatric Patients. Journal of Religion and Health, 62(3), 2181-2195. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10943-022-01672-9

Zhao, G., Cheng, Q., Dong, X., & Xie, L. (2021). Mass hysteria attack rates in children and adolescents: a meta-analysis. Journal of International Medical Research, 49(12). https://doi.org/10.1177/03000605211039812

Zhao, Y., Wang, Y., Yao, X., Jiang, L., Hou, M., & Zhao, Q. (2019). Reliability and validity of the Chinese version of spiritual needs questionnaire with 27 items (SpNQ-Ch-27) in cancer patients. International Journal of Nursing Sciences, 6(2), 141-147. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijnss.2019.03.010

Citation:

Aya-Roa, K. J., Beltrán-Campos, V., García-Campo, M. L., Vargas-Escobar, L. M., Hernández-Mariano, J. A., (2025). Psychometric Properties of Tools for Assessing Spirituality: A Scoping Review. Salud Mental, 48(1), 47-66. https://doi.org/10.17711/SM.0185-3325.2025.006