INTRODUCTION

Intimate partner violence (IPV) is one of the most common types of violence experienced by women. Globally, according to the World Health Organization (WHO), between 30% and 38% of women have experienced IPV in their lifetime (García-Moreno et al., 2013). According to the 2018 FORENSIS report on Colombia, there were 49,669 recorded episodes of IPV in which a man was reported as the principal aggressor. The main reasons reported for these acts were intolerance in relationships (21,942 cases); jealousy, distrust and infidelity (16,419 cases), and alcoholism (6,162 cases) (Instituto Nacional de Medicina Legal y Ciencias Forenses, Grupo Centro de Referencia Nacional sobre Violencia, 2018). In the Gender Observatory 2019, 7,380 cases of IPV against women were recorded in Valle de Cauca, a 21% increase over the previous two years. One hundred and twelve feminicides were also reported during the same period (OGEN (Observatorio de Género), 2019).

The WHO defines IPV as behavior by a current or former intimate partner that causes physical, sexual or psychological harm, including physical aggression, sexual coercion, psychological abuse, and controlling behaviours (World Health Organization, 2019). The notion of violence is influenced by the beliefs, values, and behaviours shared by a social group in their social context. Individually, it is expressed through language, attitudes, and a propensity towards violence. At a collective and organizational level, it is expressed through the community and the way it organizes its response to violence. A person`s mindset is the result of the internalization of their needs in their social environment and the cumulative exposure to their social conditions. This leads to the creation of propensities influenced by a person`s unique experiences, which subsequently, through symbolic production, become instruments of domination and power expressed through categories embedded in consciousness and language (Hanks, 2005). Part of what it means to be a man or a woman in a specific context is therefore related to the expression of violence, the right to exert power and its violent consequences (Pineda Duque & Otero Peña, 2004).

Violence, a multilevel problem

Every relationship is assumed to have a power dynamic. In this respect, Eric Dunning considers power to be a fundamental aspect of all human relationships (Dunning, 1999). Power is exercised dynamically and can be observed through discourse, propensities, and the way everyday circumstances are perceived. The effectiveness of power depends on whether it is legitimized by others, meaning that external coercion become internal coercion (Dunning & Maguire, 1996). Within families, strategies for the production and reproduction of power are not based on conscious or rational intentions, but rather on everyday practices and representations regarded as natural (Chevallier & Chauviré, 2010).

According to Muehlenhard & Kimes (1999), IPV is a reflection of the positions and propensities of subjects in terms of power, enabling the power holder to discredit certain acts (their own and others) and ignore or even absolve others (Muehlenhard & Kimes, 1999). In a review of the history of the social construction of sexual and domestic violence, these authors describe how IPV was invisible in the United States three decades before the publication of their article. They explain how IPV was supported by laws that validated the “disciplining” of wives by their husbands. A review of IPV in the past decade by Hardesty & Ogolsky (2020) found that although the number of reports of victimization by men had significantly increased, all the studies reviewed reported that the majority of victims were women (Hardesty & Ogolsky, 2020). IPV events reported by men mainly involved physical violence, whereas for women, they were primarily of a physical or sexual nature.

It is usually difficult for people to recognize themselves as violent and their own behaviours as violent. In practice, in IPV it is often difficult to categorize acts of violence into one type. For example, sexual abuse can include physical violence (such as hitting, suffocating, or threatening with weapons) and emotional violence (such as humiliation or making someone feel guilty). These behaviors, in turn, are facilitated and permitted by other mechanisms that may go unnoticed such as economic violence (not allowing a person to have a job or autonomy handling money) or social violence (limiting a person’s contact with their family, friends, and health networks) (Bergen & Bukovec, 2006).

Hardesty and Ogolsky quote M.P. Johnson, who identifies two main types of IPV that exists at the relationship level: coercive control (intimate terrorism) and situational partner violence. The first type consists of domination, isolation, and denigration while the second relates to specific situations (such as lashing out after verbal insults or discovering infidelity) in which conflicts and emotions intensify in one or both partners who engage in violence. According to the authors, coercive controlling behavior was mainly found to be exercised by men.

At the relationship level, one of the strongest intergenerational predictors of IPV is a history of abuse between one’s parents or child abuse by one’s parents. At a community and sociocultural level, the literature reviewed shows higher levels of violence in environments where gender asymmetry is overt, patriarchal norms prevail, socioeconomic conditions cause high unemployment rates and low average incomes, and violent behavior is tolerated (which discourages intervention) (Hardesty & Ogolsky, 2020). However, factors such as gender inequalities and patriarchal structures of domination alone have proven insufficient to explain IPV, particularly in social contexts where such differences are less evident. In such contexts, male backlash can occur, often as a means of preserving their dominant role. This can result in an increase of violent behaviours (Bourdieu, 2001; Guzmán Ordaz & Jiménez Rodrigo, 2014).

Study sites

This study is part of a preliminary qualitative phase of a more comprehensive study (Evaluation of a Cognitive-Behavioral Intervention for Victims of Domestic Violence in Cali and Tuluá, Valle de Cauca) designed to understand the situations, signs, and behaviors people identify as being associated with IPV. It was conducted in two municipalities in Valle de Cauca, a province in southwestern Colombia with a population of approximately 4.6 million inhabitants. Despite the abundance of natural resources in this area, high levels of socioeconomic inequality exist, resulting in widespread violence, informal employment, and unemployment. Cali is the capital of the province, with approximately 2.2 million inhabitants and a homicide rate of 44.77 per 100,000 population in 2022. One of the two study sites, Comuna 20, is a particularly impoverished, violent neighborhood in the west of the city. The other one, Tuluá, is a medium-sized city close to Cali with approximately 200,000 inhabitants and a homicide rate of 68.45 per 100,000 population in 2022 (Forensis,2022; Lennon et al., 2021). Both territories are ethnically diverse, with most inhabitants failing to identify with a particular ethnic group. Both territories have a strong Andean influence, which has a highly patriarchal social structure. A significant proportion of this population were from Andean agricultural regions and displaced by the internal armed conflict (Centro Nacional de Memoria Histórica, 2020).

The purpose of this study was to analyze the attitudes towards IPV of heterosexual men from two different areas of Valle de Cauca province: Comuna 20 in Cali and Tuluá. The study was undertaken to contribute to the design of educational and therapeutic interventions tailored to the local context. The interventions will not be described here.

METHOD

This exploratory qualitative study used focus group discussions to collect data.

Participants/Sample description

Approximately six men were included per focus group discussion and recruited using the following inclusion criteria: adults aged over 18 years old and residents of Comuna 20, Cali or Tuluá. Men were invited through local community leaders. This was followed by snowball sampling to recruit other men who were contacted by telephone to confirm their participation; the sample included local community leaders. A total of six focus groups were conducted: three in Cali and three in Tuluá. Volunteers were invited to participate in a group interview on the topic of “couple situations/dynamics.” A total of 33 men from the two municipalities participated. Despite the small number of participants, we decided not to conduct more focus groups due to the saturation of responses.

Data Collection

Sociodemographic data on participants was collected through a questionnaire conducted during the first focus group discussion. Trained facilitators (psychiatrists and social workers) conducted all focus groups. Written consent was obtained from all participants and permission requested to audio-record the sessions so that they could be transcribed for analysis. Groups were conducted between June 2017 and October 2018, with sessions lasting from 60 to 90 minutes. Facilitators used a discussion guide based on hypothetical scenarios adapted from the WHO Multi-Country Study of Women’s Health and Domestic Violence against Women (García-Moreno et al., 2005). The scenarios were used to encourage discussion and allow facilitators to focus on male beliefs and attitudes towards IPV. Specific attention was given to understanding the nuances of their relationships and the factors contributing to conflict. Questions such as How would you describe your relationship with your partner? And What factors do you believe contribute to conflicts in your relationship? were included. These open-ended questions allowed participants to provide rich, detailed accounts of their experiences, capturing the complexity of IPV within their specific socio-cultural contexts.

Analysis

A qualitative thematic analysis was conducted on the focus group transcripts. The unit of analysis was the transcribed texts. Information from the interviews and focus groups was transcribed in Microsoft Word® and subsequently exported and analyzed with Atlas.ti® software version 8.4.5.

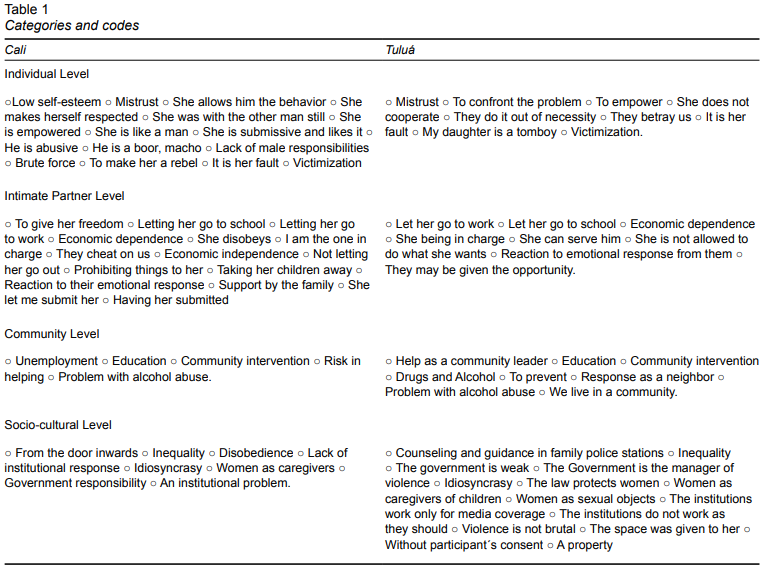

The analysis was conducted in two separate hermeneutic units, one for participants from Cali and another for those from Tuluá. Open coding and In-Vivo techniques were initially used on the transcripts. The codes were then grouped into categories according to the socioecological model. For this purpose, we referred to the article by Hardesty & Ogolsky, (2020). From this perspective, we analyzed the individual, relational and community levels, subsumed into the socio-cultural level. This permitted a comparison of the two groups of men to establish similarities and differences (see Table 1).

Ethical considerations

The study was approved by the Institutional Human Ethics Review Committee (Spanish acronym CIREH) at the Universidad del Valle, Cali (internal registration code 043-017).

RESULTS

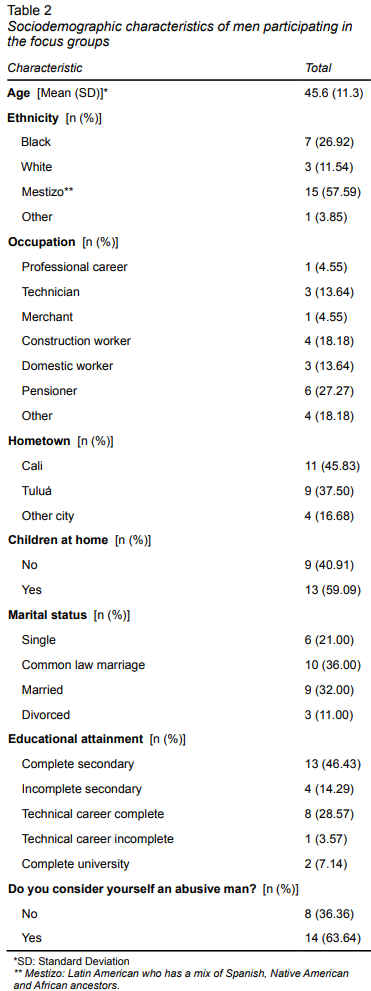

The average age of the participants was 46 years. The most prevalent sociodemographic characteristics included mestizo ethnicity (being of European and Indigenous descent), common-law marriage, having completed secondary school and being a retiree.

Although socioeconomic status was not obtained for participants, 83% of residents from Comuna 20 are in the two lowest socioeconomic groups (groups one and two out of six in Colombia) whereas in Tuluá, 75% of residents belong to groups two and three. At the end of the sessions, participants were asked if they thought they had ever been perpetrators, with 64% answering affirmatively.

Recognizing Violence

The study participants recognized a wide range of situations that could be described as violence towards women, whether psychological, social, physical, or sexual. In most of these situations, economic domination was a strategy that both caused other types of IPV: “Psychological violence, mostly…because of the financial aspect, the financial threat” (GFC1. 1:28), “…she has four children, but she does not leave him, and she puts up with it because he feeds the children even though they are not his…” (GFT3, 3:12).

Individual Level

In the statements made by the group of men from Cali, low self-esteem was a key factor in IPV in both men and women. The men explained that this permitted men’s aggressive attitudes and made the women submissive. “…women have lost their self-esteem and have made us aware of that, so that we men… I don’t know, so that we don’t respect them”(GFC1, 1:2). Participants explained that from a man’s point of view, low self-esteem translated into mistrust and fear of being abandoned, “fear that she will go off with someone else…” (GFC1, 1:9). “There are husbands who are very jealous and will think she is going somewhere to be with other men…” (GFC2, 2:4) and of course, aggressiveness “…a jealous man can go as far as committing feminicide…” (GFC1, 1:17).

Men also identified as victims of IPV, especially in terms of physical violence, “…a shouting match, a woman and a man shouting because they are hitting each other, because women also hit men!” (GFT1, 1:4). They also mentioned experiencing psychological violence, which could elicit an aggressive response on their part. However, they remarked this was accompanied by a sense of shame, as they feared social questioning of their masculinity “…the thing is that we, as men, are embarrassed to say it. These sorts of situations will never be heard around a dinner table” (GFC1, 1:30).

A consensus was observed in the groups of men in Cali and Tuluá that women brought IPV upon themselves but that they too were perpetrators. This was explained by the lack of limits women imposed on their partners, “From the moment he does it for the first time and she allows it by not creating a barrier or putting an end to the situation, he will keep hitting her” (GFC3, 3:23), as well as attitudes or behaviours that can be seen by them as triggers of violence “…there are many women who demand respect but when you see how they dress, it’s inconsistent … many men disrespect them, they touch them and women incite them to do inappropriate things because of their own behavior…” (GFC1, 1:2) They also attribute certain characteristics to women such as infidelity, suggestibility and weakness in response to external household stimuli, “…in my neighborhood there is a lot of violence, there are many girls walking around in the street, girls as young as eight or ten years old who already allow others to grope and touch them…” (GFT1, 1:2). This places men in a reasonably distrustful position “you have to be very careful about her plans to study, because she may be looking to engage in some kind of lewd behavior…” (GFT3, 3:11).

Both groups of men perceived female empowerment as a protective factor against IPV, particularly those who had the strength and courage to denounce it and to become financially independent. However, they tended to masculinize women who adopted strong positions or engaged in activities regarded as inherently masculine “look, she is like a man…” (GFC1, 1:8), “…I have a little man…” (GFT1, 1:7).

Couple Level

In the discourse regarding the men from Cali and Tuluá, there is a permanent emphasis on power for men-fathers, husbands, boyfriends-to prevent women from performing various activities. There is an established power dynamic that affects the possibility of subverting power relationships at home, as well as in education and workplace settings, “…sometimes we do not allow women to work for that reason, so they understand that it is the man who… And always to dominate them, given that it is the man who puts bread on the table…” (GFC3, 3:28). The relationship between domination and violence is recognized by both sets of municipal men, since their discourse concerns violence, rather than power relations, “…when he has a beer, he comes home with the aim of … making his authority felt, which creates conflict” (GFT2, 2:3).

Traits of domination in relationships were said to be passed on from fathers to sons and those of submission in relationships from parents to daughters. Physical violence as a form of communication was also described as being passed on from generation to generation, “…well, I am a macho man, I followed my dad’s example and you can’t do that because you can’t leave the children alone… you must look after my children… you must look after them, you can’t do anything else…” (GFT3, 3:4). This shows how both women and men observe their parents’ behaviours in childhood and repeat them in their own couple relationships.

Participants from both locations described cases in which IPV committed by men responded to emotionally charged situations that women had initiated. They gave examples of women who were jealous, or complained about their behavior outside the household or money, and of expressions of vulnerability within the relationship itself, which led to intimate partner problems, “…the truth is that I told her: I’ll put you on a leash and hit you, because there is often no need for women to curse and treat you…with hurtful words” (GFC2, 2:21).

Regarding the role of families in IPV, there was no clear consensus on whether it was a protective or risk factor. Some men described how families would attempt to contain it, whereas others remarked that if the family became aware of the situation, the violence could escalate.

Community Level

Participants in Cali regarded unemployment as one of the causes of IPV, which put pressure on their relationships as their partners were described as having many financial demands: “Due to the lack of employment, there are also many domestic problems, there are women who demand too much from you as well…” (GFC3, 3:32). Men from both cities identified the use of alcohol and other psychoactive substances as facilitating factors for IPV, which were used by men to externalize their emotions that would otherwise remain repressed, “…my dad used to drink and beat my mum. He left her but every time he got drunk, he would go and beat her…” (GFC1, 1:26), “…some of us become more loving, … others become aggressive. I gave up drinking ten years ago, but when I drank, I was very aggressive. I used to hit my partner for the slightest reason…” (GFC3, 3:19).

The community’s involvement with IPV was seen by participants from two different perspectives: on the one hand, they realized how local leadership initiatives could alleviate it, whereas on the other, they felt it could perpetuate more violence. They mentioned community projects that offered training regarding IPV such as educational strategies targeting children and young adults, information on their rights, the law, and places where women could obtain help in the event of IPV, “I live in a community where there has been a lot of violence against women and well, in our neighborhood we have been working on this with the community… providing training sessions…” (GFT1, 1:36). They identified the need to change gender stereotypes in the household. They identified lack of education as another determinant of violence, stating that it should begin in childhood. One the other hand, there was a consensus that intervention in IPV cases would be too risky. They feared negative consequences for themselves and/or the woman involved and explained how this could lead to passivity and tolerance of violence in their neighborhoods, “…because he defended a woman who was being beaten...a man was caught at the liquor store and bar the following Sunday and shot four times in the head, he never messed with anyone, they worked together! He was one of the good guys here and because he got involved…” (GFC2, 2:14), “No, that’s someone else’s problem. That’s the typical phrase of people who think I’m not getting involved because that’s not my problem. But it is your problem, because that’s precisely why violence is generated in the neighborhoods” (GFT1, 1:32).

Socio-cultural Level

A strong patriarchal structure was evident in the accounts of men from both cities, speaking of clearly defined gender roles transmitted by men and women with entrenched sexist beliefs, “Even the mothers were sexist.” (GFT3, 3:1) “…we believe that women’s place is in the kitchen and we have created an imaginary that women are the ones who do the housework… because we end up drinking beer, but if she wants to go out, if she wants to share a moment with a family member, she can’t because she is a woman. So, these situations lead many of them to be mistreated and psychologically abused.” (GFC1, 1:3-4). The position of male dominance was also observed to delineate the physical space participants believed to be appropriate for men and women. They believed that the street was a natural space for men and the household for women where they cook and take care of the children: “At the local scale, Tuluá is a very sexist city... because of this, a man from Tuluá who is able to support his family and who has deeply rooted traditional principles, would normally not allow his wife to work.” (GFT1,1:17).

Financial power was one of the most widely recognized factors through which the positions of domination and submission in the couple were perpetuated: “…to make her understand that he is the one in charge …men sometimes don’t let women work for that reason, so they know the man is in charge, and will always dominate her. Since it is the man who puts bread on the table… you understand…and many men bring that up whenever there is a problem… If you don’t work, I am the one who provides for the household. So, they can’t say anything. This is called manliness, machismo…” (GFC3, 3:28).

In Tuluá, men described how the sexual objectification of women was heavily influenced by the drug trafficking culture present in the central and northern part of the Valle de Cauca, “…it (IPV) increased in households because of the phenomenon of drug trafficking when they (drug traffickers) acquired economic power and women became sex toys and were increasingly seen as objects rather than as human beings with the same rights and possibilities...” (GFT3, 3:2)

Regarding the government’s role, men from both cities were aware of the laws and government institutions in place to both prevent and mitigate IPV. However, they perceived the government’s response to be limited, untimely and delayed, “Here, women have received death threats, and they don’t even pay attention to that…” (GFC1, 1:25). Participants from Tuluá felt that the government was responsible for IPV, and blamed corruption and indolence among civil servants for encouraging it, “…nowadays institutions work by merely taking a picture (of their work) and... publishing it in the media... because I experienced that myself... I had to take pictures to send them to the office to show that work was being done, but it was a fake job.” (GFT1, 1:35).

DISCUSSION ANDCONCLUSION

The ecological model provides a contextualized view of the IPV, by exploring the levels of analysis, with interdependent, dynamic relationships, making it possible to understand individual aspects such as gender in relation to the socio-historical conditions of the latter and the environment in which they develop (Crego Díaz, 2003).

In our study, we did not find any significant differences in the perspectives of intimate partner violence (IPV) between participants from Cali and Tuluá. However, it is crucial to consider the broader context of each region when interpreting these results. For instance, Tuluá has a significantly higher homicide rate (68.45 per 100,000 population) than Cali (44.77 per 100,000 population) (Forensis, 2022). This disparity in violence rates may be influenced by factors such as socioeconomic conditions, the presence of armed groups, and urban violence dynamics. These contextual differences might not directly affect the individual perceptions of IPV but are likely to impact on the overall environment of violence in which these individuals live (Moser & McIlwaine, 2006).

The discussions in the focus groups for men in this study show that the vulnerability of both men and women is associated with IPV, cutting through all levels of the analysis: the individual, the couple, the community and society and culture. Kabeer, (2014) describes vulnerability as being “…conventionally conceived as a dynamic, multidimensional concept that relates to the choices that people can exercise and the capabilities they can draw on in the face of shocks and stresses.” (Kabeer, (2014); Kabeer et al., 2013). This author prefers to use the term “relational vulnerabilities” when explaining IPV against women as it better describes the existing unequal social relationships and the resulting dependencies.

Examples of vulnerability in both women and men, across all levels found in this study include low self-esteem, a fragile couple relationship, family background, including a history of exposure to violence between parents and child abuse, psychoactive substance use, and external conditions that directly impact relationships (such as unemployment, low educational attainment, lack of support from family and neighbors, gender inequalities, and passive or negligent government intervention). Some of these conditions of vulnerability are often used by men as excuses and justifications for acts of violence. However, at the same time, they reflect the contradictory experiences of power and powerlessness perceived by men, a conclusion also highlighted by Pineda Duque & Otero Peña, (2004).

Vulnerability as a trigger for and perpetuating factor of IPV is consistent with findings described by other authors, at the individual, relational, community and societal and cultural levels as shown in Hardesty and Ogolsky’s review of research on IPV over the past decade (Hardesty & Ogolsky, 2020).

Although men rationally questioned overt scenarios of violence and mentioned situations in which they had exercised different forms of IPV, they failed to identify the influence of unequal power between the sexes as underlying IPV. Gender inequality, manifested in the participant’s statements, reflected the internalization of a patriarchal social structure known to exist in both study territories; Cali’s Comuna 20 and Tuluá, which both experienced a strong cultural influence from rural migrants from Andean agricultural regions in Valle de Cauca and the surrounding regions.

Gender relationships are a result of everyday activities and interactions. At the same time, behavior in the private sphere is directly associated with collective social propensity in terms of three social aspects that interact together to form the gender order: work in both the household and the labour market; power through social relationships such as authority, violence, domestic life, institutions; and cathexis, which relates to the dynamics of intimate relationships, such as marriage, sexuality, and parenting (Giddens & Sutton, 2021).

Giordano et al., (2015) used a symbolic interactionist approach to analyze young couples, finding that in regard to the dynamics of control and IPV, IPV occurred more when couples argued rather than as a general attempt to dominate (Giordano et al., 2015). This and other findings led them to conclude that it could be useful to conceptualize control mechanisms as an indicator of vulnerabilities in the relationship rather than a direct assertion of male privilege or dominance. In view of this, we conclude that, according to our findings, although there was no conscious intention of men to assert their power and dominance over women, men and women were ‘placed’ in their gender condition because structural inequality influences individual level. This reflects the internalization of roles through barely sustained propensities, particularly evident in patriarchal societies. Anderson also referred to the concept of “social location,” which assigns gender specific behaviours and ways of perceiving or negotiating their identities at a micro-level of social interaction (Anderson, 2010).

The findings of this study suggest that there is a need to intensify multilevel preventive interventions rather than conducting targeted interventions for victims and perpetrators. Coordinated community responses to IPV have been shown to be effective in reducing recidivism and holding perpetrators of violent behavior to account. This requires the engagement of key actors at each level: the individual (survivors and perpetrators), families, community groups, and protection, justice and health systems, etc. (Pallatino et al., 2019).

Lastly, it is also necessary to address vulnerabilities early on in childhood (such as household relationship patterns, gender equity at school, support in primary care during the teenage years), and to strengthen responses to IPV by the community and health, protection and justice institutions, all of which must be supported by robust national legislation.

Men in this study recognized different forms of violence targeting female partners, with most of them self-identifying as perpetrators of this type of violence. Economic, structural and gender inequalities were expressed at the individual, couple, and socio-cultural levels. Participants rationally questioned overt scenarios of violence yet failed to identify the influence of unequal power between sexes as underlying IPV.

DECLARATIONS