INTRODUCTION

In contemporary society, work not only constitutes a source of income, but also a fundamental pillar of identity and well-being (Kun & Gadanecz, 2019). Since work is a center of satisfaction and concern in people’s lives (Inayat & Jahanzeb, 2021), workplace well-being has become a critical consideration in both business management and public health promotion (Eriksson et al., 2017). Well-being at work is an essential concern in human resource management and public health (Peters et al., 2022), forming part of the global assessment of the physical, emotional, and mental state of employees in a work setting (Adams, 2019). The growing importance of the concept of well-being at work is due to its potential to influence productivity, job satisfaction and, ultimately, the Quality of Working Life (Leitão et al., 2021).

Organizational and working conditions can contribute to the deterioration of workers’ mental health, manifesting as stress, depression, anxiety, substance use, and absenteeism (Irarrázaval et al., 2016; Mingote et al., 2011). Companies have a mission to raise awareness about the need for well-being at work, adapting and evolving in response to the needs of their employees (Zhenjing et al., 2022).

The intersection of mental disorders and workplace inclusion has emerged as a critical area of study in the relationship between public health and the work world (Bjørnshagen & Ugreninov, 2021). Mental disorders (MD), comprising a wide range of conditions affecting emotional and psychological health (Gross et al., 2019), represent a significant burden on society in terms of human well-being and financial costs (Tham et al., 2021). In this context, people’s capacity to access and maintain employment becomes a crucial aspect of their recovery and quality of life (Brouwers, 2020).

Human Resources (HR) are the communication channel between management and employees (Mayon et al., 2019). As the guardians of an organization’s workforce (Renwick, 2003), HR professionals have the power to influence the inclusion or exclusion of those with MD in the workplace (Hennekam et al., 2021). Their capacity to understand, support and foster inclusive work environments can be decisive in the lives of those facing mental health challenges (Wu et al., 2021).

Stigma and discrimination continue to be significant barriers to effective mental health management in the workplace. When an individual with a MD engages in competitive employment, either by applying for a job or returning to work after a diagnosis, the stigma associated with their condition poses challenges, especially if it is considered a disability (Dinos et al., 2004; Hielscher & Waghorn, 2017).

The decision of whether to disclose a MD to the organization is crucial because it determines the consequences an individual may face as a result (Honey, 2004). For organizations, MD disclosure presents challenges due to the attendant financial and legal liabilities. For this reason, individuals with a MD remain vulnerable not only to the symptoms, but also to coworkers’ and employers’ negative reactions, many of which are based on unfounded stereotypes about their capacity (American Psychiatric Association, 2013). A quantitative study reported that disclosure resulted in discriminatory responses, including work dismissal, differential treatment, changes in attitude by interviewers during the recruitment process, exclusion from task accomplishment, and avoidance by coworkers (Gladman & Waghorn, 2016).

Variations in mental disorder diagnoses also shape the decision to disclose. Some studies reveal that the less outwardly visible the symptoms of an MD, the less likely an individual is to disclose. One survey found that participants with depression were more likely to conceal their MD than those with schizophrenia, schizoaffective disorder, or bipolar disorder (Yoshimura et al., 2018).

Brohan et al. (2012) observed that individuals with MD perceived that employers tend to have low levels of mental health literacy, largely because they are highly influenced by stereotypical media attitudes towards those with MD. This, in turn, leads to negative behaviors, including rejection, condescension, disdain, and patronization.

HR perceptions, attitudes, and practices can make the difference between successful workplace integration and persistent discrimination (Kunz & Ludwig, 2022). Although instruments exist to evaluate opinions toward those with MD in community settings (Grandón et al., 2016) and among healthcare professionals (Fernandes et al., 2019), no specific instrument has been found to assess HR attitudes and opinions regarding the work capacity of people with this condition.

The main objective of this study is to explore the attitudes and opinions of HR personnel towards people with MD in companies in Guadalajara, Puebla, and Mexico City (CDMX). To achieve this, a scale was designed and validated to reliably quantify the attitudes and opinions regarding the work capacity of this population. The comprehensive approach of this research aims to shed light on the relationship between HR personnel and individuals with MD in the workplace, to encourage their effective understanding and inclusion in the work environment.

METHOD

Study Design

This study was observational, analytical, prospective, and cross-sectional.

Sample description

The sample comprised 62 participants working in the HR area of companies located in three cities in Mexico: Guadalajara, Puebla, and Mexico City (CDMX). The initial design included invitations to HR professionals through social networks and visits to companies specializing in labor recruitment. Although face-to-face interviews were initially planned, many participants reported difficulties due to scheduling constraints or internal company policies. To accommodate these challenges, participants were offered two options: in-person interviews or remote interviews using a digital communication platform.

The sampling method was convenience-based, meaning that recruitment was conducted through centers identified online or in physical advertisements in the selected cities. Participants who answered these advertisements were encouraged to invite their colleagues to participate.

Since one of the objectives of the study was to validate the OCAL-TM scale, the sample size was calculated for a factor analysis. Based on recommendations in the literature, the sample size was set at 55 participants, with a minimum of five participants per item (MacCallum et al., 1999).

Sites

The study was conducted in three locations in Mexico: Guadalajara, Puebla, and CDMX. These cities were strategically selected to represent the geographic and demographic diversity of the country, providing a holistic understanding of the attitudes and opinions of HR personnel across work and cultural contexts.

Measurements

Two widely recognized scales were used to evaluate attitudes and opinions towards those with MD: The Community Attitudes to Mental Illness Scale (CAMI), developed by Taylor & Dear in 1981, and the Opinions about Mental Illness Scale (OMI), created by Cohen & Struening in 1962.

From these scales, we selected 19 items from the CAMI scale and 16 from the OMI scale for our research. Both scales use a Likert rating system, with responses ranging from 1 meaning “totally disagree” to 5 meaning “totally agree.”

For this study, a new measurement tool called Opinions of Work Capacities of people with Mental Disorders Scale (OCAL-TM) was developed to evaluate the opinions of HR professionals on the work capacity of people with MD.

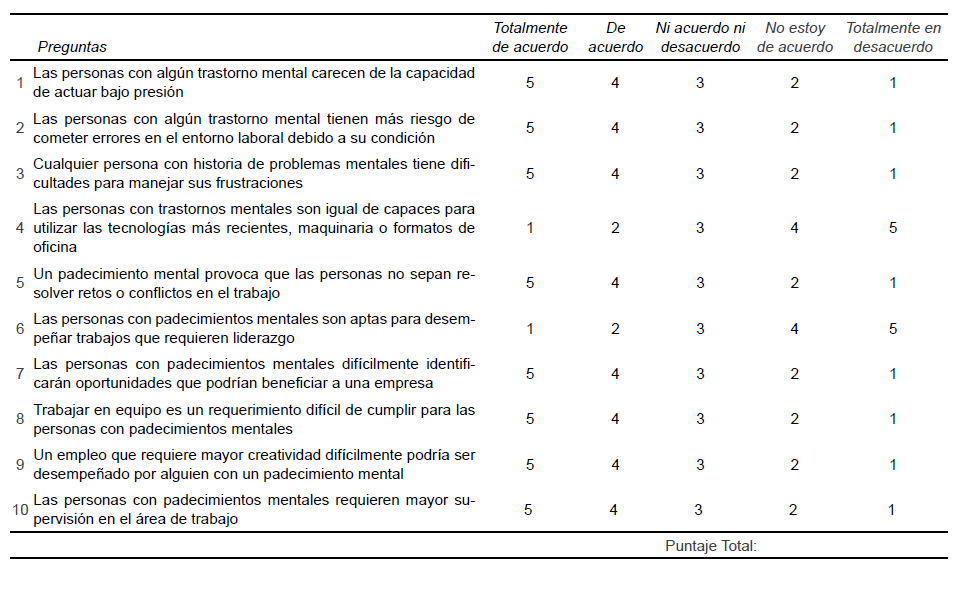

The OCAL-TM consists of 11 carefully worded questions, evaluated using the same Likert-type scale, where a higher score reflects less favorable attitudes and opinions towards people with a MD. Two occupational mental health experts developed the OCAL-TM items to ensure their relevance and validity in the context of human resources and employment. A pilot test had previously been conducted to analyze the format validity of the items.

Some items in the CAMI and OMI are reverse-scored on the Likert scale. This strategy was also adopted for the OCAL-TM to reduce potential response bias and ensure a more accurate evaluation. Combining positively worded and reverse-scored items is common practice in social research to prevent automatic responses and encourage participants to reflect more carefully, thereby improving data quality.

Reverse-score items were graded from 1 “totally agree” to 5 “totally disagree.” In the CAMI scale, reverse-scored items included numbers 4, 5, 6, 10, 11, 13, 14, 18, and 19. In the OMI, these items corresponded to numbers 6, 8, 10, 12, 13, and 14, whereas in the OCAL-TM, reverse scoring was applied to items 4 and 7.

Procedure

The research procedure was systematically conducted to ensure the collection of reliable representative data. Companies located in the three study cities were contacted to recruit HR professionals.

Data collection took place between April and May 2023, beginning in Puebla, followed by CDMX, and finally, Guadalajara. After initial contact and before the interviews, participants were sent a digital informed consent form, which they were asked to sign and return. The information collected was securely stored. Since the instruments administered were brief—including a questionnaire on sociodemographic data—interviews lasted approximately 30 minutes. Data was stored in Excel spreadsheets and securely maintained by the principal investigator.

Statistical analysis

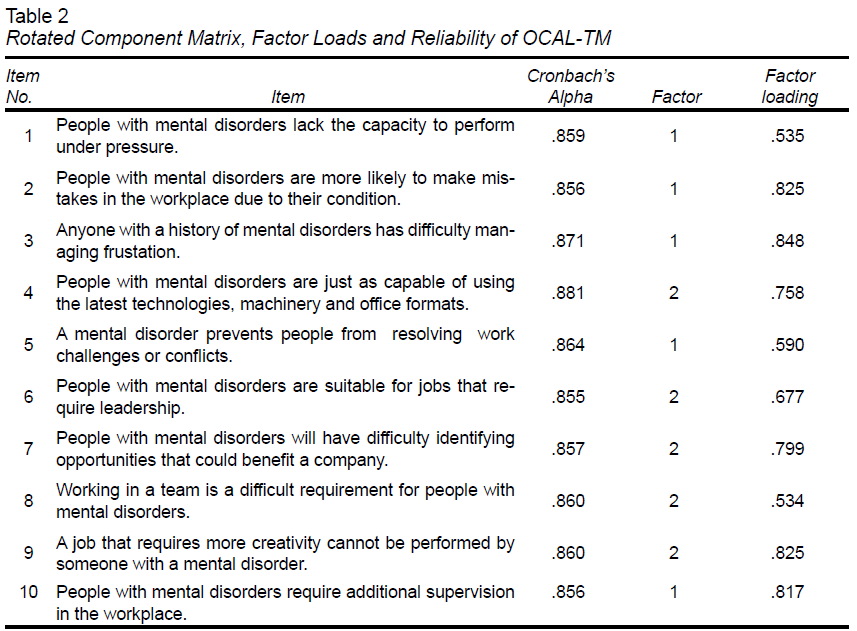

To compare the total scores across the three cities, a statistical analysis was conducted using the Kruskal-Wallis test. To validate the OCAL-TM scale, Cronbach’s alpha was calculated to assess reliability, and Spearman correlations were used to evaluate validity. All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS v21 to ensure accurate data evaluation. The OCAL-TM scale was validated using principal component analysis with varimax rotation, yielding two factors that explained 63.44% of the variance. A factorial load of 0.40 or more was established as the criterion for retaining an item.

Ethical considerations

Ethical approval was obtained from the Research and Ethics Committee of the Faculty of Medicine of the Benemérita Universidad Autónoma de Puebla (BUAP), on March 30, 2023, with registration number 1029. The project, classified as negligible risk, adhered to the principles of the Helsinki Declaration and the Belmont Report.

All data were anonymized and stored by the principal investigator to protect confidentiality. These measures were outlined in the informed consent process, providing transparency regarding the security of participant information.

Participants were offered the opportunity to receive a summary of the findings once the study had been completed. This reflects the commitment of the study authors to transparency and ensured that participants would be informed of the outcomes of the research to which they had contributed.

RESULTS

In accordance with the methodological framework outlined above, the following section presents the results obtained from the comprehensive analysis of the data collected. These findings provide a detailed examination of the attitudes and opinions held by HR professionals towards individuals with mental disorders in the workplace.

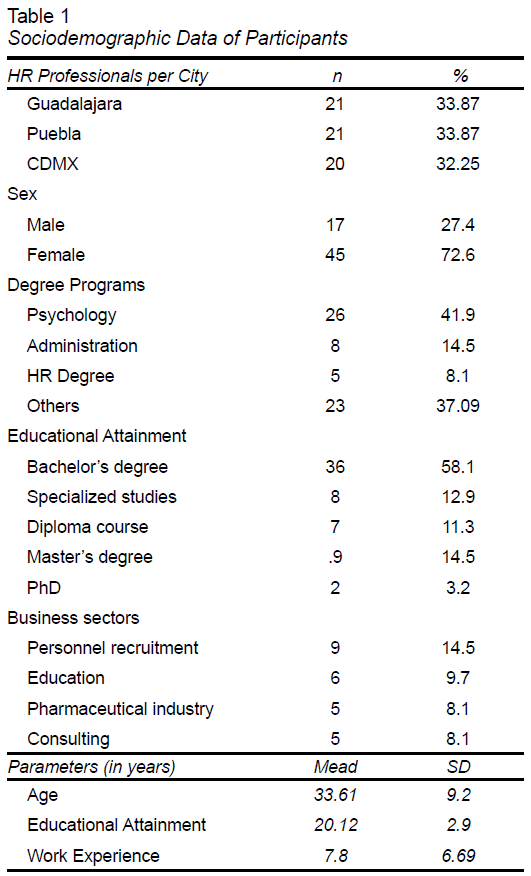

Sociodemographic data are given in Table 1 with percentages, means and standard deviation depending on the characteristics of each variable. A total of 62 interviews were conducted with HR professionals in companies in Guadalajara (n = 21), Puebla (n = 21), and CDMX (n = 20).

Forty-five of the participants were women (72.6%), and the average age was 33.61 (SD = 9.2). The mean level of educational attainment was 20.12 years (SD = 2.9). Average work experience in HR was 7.8 years (SD = 6.69). A wide range of academic backgrounds was observed, with participants having pursued 17 different degree programs. The most common fields of study were psychology (41.9%), business administration (14.5%) and HR management (8.1%). Regarding postgraduate studies, 58.1% of participants had not pursued further studies, 12.9% had completed specialized studies, 11.3% held graduate degrees; 14.5% master’s degrees and 3.2% doctorates. HR professionals worked across 23 business sectors, the most common ones being personnel recruitment (14.5%), followed by education (9.7%), with a tie between the pharmaceutical industry and consulting (8.1%).

No significant differences were found in the age and education variables in the cities studied. However, variations were observed in the number of years of work experience. In CDMX, the average number of years spent in HR was 10.22, with 7.8 in Guadalajara 7.8 and 5.7 in Puebla.

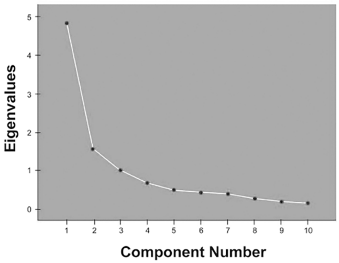

Regarding the validation and structure of the OCAL-TM, data from the screen plot and eigenvalues were used to determine the optimal number of factors. This analysis indicated that the most appropriate configuration for the scale consisted of two factors, as shown in Graph 1. During this process, item 5 was eliminated due to its reduced factor loading (< .40). The final scale therefore comprised 10 items (as shown in Table 2), showing that two factors accounted for 63.44% of the variance, and demonstrating high reliability with a Cronbach’s alpha coefficient of .874.

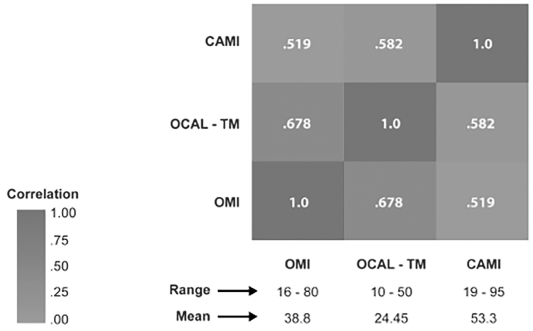

Graph 2 is a heat map based on Spearman’s test between the three instruments analyzed. Statistically significant correlations were observed between the three scales, with a significance level of p =< .000. Correlations between OCAL-TM and CAMI, and OCAL-TM and OMI was higher than the correlation between OMI and CAMI.

To assess the degree of stigma or discrimination towards people with MD, the possible scores on each scale were analyzed and the mean was examined in the studied sample. The last quartile of the values was calculated, enabling us to identify the number of participants who obtained extremely high scores, indicative of less favorable attitudes and opinions towards people with MD. The results revealed that 18 participants obtained extreme values on the scales. Seven of these 18 participants obtained a score in the last quartile on the three scales, while the remaining 12 did so on the OMI and OCAL-TM scales.

DISCUSSION

The results of this study provide detailed insight into the attitudes and opinions of HR towards people with MD in three cities in Mexico. Most participants were women, reflecting the feminization of the HR labor market. Additionally, the variety of professions and work experience suggests that HR professionals are drawn from various contexts.

The presence of 18 individuals with exceptionally high scores on the scales suggests the possibility of potentially discriminatory attitudes and opinions towards individuals with MD. No significant statistical differences were found in attitudes and opinions towards people with MD among the cities studied, suggesting that geographic location and the specific context of each city do not affect these perceptions. The absence of differences, however, does not necessarily indicate positive attitudes. On the contrary, it could reflect a generality of less favorable attitudes toward people with MD.

The Opinions of Work Capacities of people with Mental Disorders Scale (OCAL-TM), constitutes a valuable tool for understanding the opinions of HR personnel of the work capacity of individuals with MD. It addresses the need to evaluate and understand the attitudes and opinions of HR personnel, who wield enormous influence in shaping organizational culture and formulating wellness policies.

Comprising 10 items, the OCAL-TM demonstrated high reliability and validity, with a Cronbach’s alpha coefficient of .874 and moderate correlations with scales used to measure opinions in the general population (CAMI) and among health professionals (OMI). The correlation observed between the scales, supported by Spearman’s test, indicates good concurrent validity among these scales. This cohesion suggests that HR personnel attitudes and opinions towards people with MD, as assessed by the OCAL-TM, consistently align with the general attitudes of the population and health professionals. This finding reinforces the importance of the OCAL-TM in the field of HR, highlighting its usefulness as a valid indicator of prevalent attitudes towards mental health at work. This underscores its role as an indispensable instrument for future research and comprehensive evaluations within the realm of human resources and labor inclusion. To strengthen its external validity, it should be administered to professionals other than HR personnel, which would allow for a broader evaluation of its usefulness and permanence. The OCAL- TM not only contributes to the internal understanding of HR perceptions but can also be used as an external tool to sensitize organizational leaders and other professionals to the importance of fairly and inclusively assessing the job skills of people with MD.

In a world where well-being at work is essential to public health and the quality of life of workers, the perceptions and understanding of HR professionals play a critical role.

This study underscores the need to address the negative attitudes and opinions identified. Fostering a culture of inclusion and eliminating stigma are key steps towards equitable work environments, regardless of mental health condition. Furthermore, the disclosure of an MD is the result of an interaction between internal and external factors. An individual’s decision does not stem solely from the individual self but is also indirectly influenced by the environmental context acquired through social interactions (Hastuti & Timming, 2021). Social support plays an essential role in the disclosure process. It is therefore necessary for companies to promote mental health education, to prevent discrimination, prejudice, and stereotypes in the work environment.

Recognizing the influence of HR on organizational culture and mental health, this critical analysis highlights the urgent need to overcome existing barriers and promote workplace inclusion. Since functional recovery is a central aim of modern psychiatry, the perception of HR personnel, who constitute the primary filter in the job search process, is crucial. Identifying negative perceptions, such as the lack of technological skills, limitations in resolving challenges or conflicts at work, and the inability to make decisions at critical moments, underscores the need for mental health information to promote tolerance and workplace inclusion.

Through this study, we not only respond to the need to understand internal attitudes, but also to the opportunity to lead mental health awareness and education initiatives in the workplace. We underline the need to provide HR professionals with specific information on mental health, to foster tolerance and workplace inclusion. By doing so, we contribute to creating a more equitable, healthier work environment for all people, regardless of their mental health status.

Combining tools such as the OCAL-TM with educational strategies will ultimately strengthen HR’s position in promoting an organizational culture that values and supports the mental health of all employees.

A key limitation of this transversal study is its reliance on a snapshot of data collected at a single point in time. The study may also be subject to self-report bias, as participants could provide socially desirable responses rather than accurate reflections of their behaviors or attitudes. Another limitation is the small sample size, which may restrict the generalizability of the findings. Future research should aim for larger, more representative samples to enhance the validity and reliability of results.

A major strength of this research is that it redresses the lack of information on the attitudes and opinions of HR for people with MD. We have created a scale that can be used in this setting, to further understand these factors and enable them to be addressed in every workplace.

CONCLUSION

The OCAL-TM scale, with two factors and 10 items, showed adequate psychometric properties in the sample studied. Strong correlations were observed between the three scales studied. The resulting scores were in the middle of the range for each of these instruments, meaning that a degree of stigma and/or negative attitude toward people with SMI can be observed in the studied sample. A comprehensive approach toward MD within the workplace is essential to foster inclusion and reduce stigma.