INTRODUCTION

The suicide mortality rate in Mexico has exhibited a consistent upward trend. Between 2014 and 2021, the rate rose from 6.09 to 6.84 per 100,000 inhabitants (Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation [IHME], 2024). Over the past decade, this increase reached 22%, with a higher rise among women (37%) (Borges et al., 2019). Globally, individuals aged 15–29 constitute the most vulnerable group (IHME, 2020; Organización Mundial de la Salud [OMS], 2021; Instituto Nacional de Estadística, Geografía e Informática [INEGI], 2023), with adolescents aged 13–15 showing the highest increase in lifetime suicide attempts (Valdez-Santiago et al., 2021).

The Interpersonal Psychological Theory of Suicide (Joiner, 2005) is a second-generation framework (Yöyen & Keleş, 2024) that seeks to understand why the desire to die is insufficient to predict a suicide attempt. This parsimonious theory has demonstrated empirical support and explanatory power, even when controlling for widely studied factors such as mood disorders, personality traits, or family history, and highlights the importance of interpersonal factors and social context (Chu et al., 2017; Van Orden et al., 2010).

An acquired capability for suicide (ACS) is the belief that he or she is capable of ending his or her own life. Joiner's theory posits that engaging in lethal self-harm requires habituation to fear and pain involved in self-harm (Van Orden et al., 2008; Van Orden et al., 2010; Joiner, 2005).

Thus, ACS is built on two main factors: pain tolerance and fearlessness about death (Van Orden et al., 2008). Its nomological network includes impulsivity, a related condition for its acquisition (Van Orden et al., 2010), and other variables in Joiner's model (2005; Van Orden et al., 2010; Van Orden 2015).

Instruments to measure ACS have been developed and tested in adult Anglo-Saxon populations, but adaptations and testing are needed for other vulnerable populations, like adolescents from diverse cultural contexts. Additionally, many scales fail to fully align with the two dimensions proposed by the theory (Joiner, 2005; Van Orden et al., 2008). Despite their strong psychometric properties, examples include the ACSS-FAD (Acquired Capability for Suicide Scale – Fearlessness about Death; Ribeiro et al., 2014; SRMR = .03 - .05, CFI = .93 - .99, TLI = .90 - .98, RMSEA = .04 - .06), the ACWRSS (Acquired Capability with Rehearsal for Suicide Scale; George et al., 2016; X2(11) = 17.24, p = .10, RMSEA = .030 [90% CI = .000 - .057], CFI = .997, TLI = .994, α = .83), and Rimkeviciene et al.'s proposal (2017; CMIN/DF = 2.98, RMSEA = .05, CFI = .95; R2 = 47%). Although Ribeiro et al. (2014) included 10 – 20% of Latin American participants, participants in these scales were predominantly Caucasian Australian adults.

There are other scales available to measure the two proposed factors of ACS, such as the ACSS (Van Orden et al., 2008), the GCSQ (German Capability for Suicide Questionnaire; Wachtel et al., 2014), and an adaptation of the ACSS for the Mexican population (Rangel-Villafaña et al., 2023). The GCSQ showed acceptable adjustment indices (CFI = .94, RMSEA = .09 [90% CI = .07 - 1.1], SRMR = .07, α Fearlessness about death = .90, α Pain tolerance = .77), however, it was evaluated in a Caucasian adult population residing in Germany; while no formal psychometric studies have been done for the ACSS, with only reliability being reported as α = .84 in general population. The Mexican adaptation of ACSS (Rangel-Villafaña et al., 2023) was studied with an adult general population, underwent confirmatory factor analyses, and yielded excellent adjustment indices (RMSEA = .011, CFI = .99, TLI = .99, IFI = .99, NFI = .91, X2 = 86.75, DF = 84, p = .397; α = .77). Items in Mexican Spanish were carefully chosen to suit the language and cultural context.

The main objective of this study was to obtain the reliability and structural, convergent, and predictive validity, as well as a sensitivity and specificity test of the adapted version of the ACSS (Rangel-Villafaña et al., 2023) in Mexican adolescents. An additional objective was to investigate whether the adapted scale structure is consistent for both clinical and non-clinical adolescent populations.

METHOD

The ACSS (Rangel-Villafaña et al., 2023) was adapted for Mexican adolescents by modifying item wording (DeVellis, 2017 & Furr, 2018) to ensure comprehension. Three expert judges evaluated inter-judge agreement (80% satisfaction) and provided qualitative opinions on content validity through three iterative rounds. Aiken’s V coefficient with a desired value of at least .70, Type I Error p < .05 (Charter, 2003) and its confidence interval ensuring a lower limit of at least .70 (Merino & Livia, 2009) were computed for content validity (Appendix).

To achieve the aims of this study, two phases were conducted: Phase I – Confirmatory Factor Analysis and Reliability, and Phase II – Convergent and Predictive Validity; sensitivity and specificity.

Design

Development of psychometric properties of a measurement scale.

Phase I - Confirmatory Factor Analysis and Reliability

Participants

The sample included 429 adolescents (71.3% female) aged 13 to 18 years (Mage = 15.9, SDage = 1.2). Two subsamples were recruited: non-clinical (73%) and clinical (27%). Adolescents with adequate comprehension skills, allowing them to understand and complete the items of the scale, were invited to participate.

In the non-clinical group, most participants were female (67.4%) and lived with their nuclear family (81.5%). Additionally, 80.5% of the sample were exclusively students, with 42.8% enrolled in the second semester of high school. In the clinical group, 81.9% were female, most were also exclusively students (78.4%), and 19.1% were in the third year of middle school. The majority lived with their nuclear family (63.8%). Furthermore, 93.8% presented psychiatric comorbidities, with 65.2% having three or four diagnoses, primarily mixed types (internalizing and externalizing disorders, 55.8%).

Settings

Public schools in three cities in Mexico, and the Hospital Psiquiátrico Infantil "Dr. Juan N. Navarro" (HPIJNN).

Measures

Sociodemographic Questionnaire. This consisted of general data about the participants, including their age, occupation, psychiatric diagnosis, living arrangements, and other relevant information.

Acquired Capability for Suicide Scale, version adapted for Mexican adolescents. It consisted of 23 items with six response options intended to measure two factors: Fearlessness about death and Pain tolerance.

Procedure

The scale was administered to 445 adolescents through both face-to-face and online modalities, depending on the conditions arising from the COVID-19 pandemic. Prior to participating, the adolescents and their guardians provided verbal and written assent and consent, respectively.

Bias

The items of the ACSS were randomized in the electronic version, and three printed versions were created with the items in different order.

Statistical analysis

We used IBM SPSS® version 26. Cases with near-zero or extreme standard deviations (≥ 3; Simms et al., 2019) and those with errors on the commitment question were excluded, resulting in a final sample of 429 participants. No cases or items were eliminated due to < 10% missing values. Little's MCAR test (χ2 = 76.60, p > .05) confirmed randomness, allowing simple imputation using the median of adjacent points (Pardo-Merino & Ruiz-Díaz, 2005).

To analyze the original scale's structure, we used IBM SPSS® AMOS graphics version 26. Items were examined for variance explained (≥ .20; Hooper et al., 2008) and factor loadings (≥ .40; Bandalos & Finney, 2010; Guadagnoli & Velicer, 1988; Hogarty et al., 2005). Items with values below these cutoff points and with high correlated errors were considered for elimination if theoretically justified (Brown, 2015; Pituch & Stevens, 2016; Lloret-Segura et al., 2014). Adjustment indices calculated included Chi-squared/Degrees of freedom (< 3), Comparative Adjustment Index (CFI ≥ .95), Mean Square Error of Approximation with 90% confidence interval (RMSEA < .05), and pClose (p > .05) (Hu & Bentler, 1999). We maintained those items that made the best contribution to the evaluated model.

If the scale did not meet desirable adjustment indices, items from the item pool constructed during the content validity were added to improve structural validity. This iterative refinement process, along with the specification and respecification of the model, continued until satisfactory fit indices were achieved, without neglecting the individual contributions of each item.

Total scores were calculated for each respondent. Since data were not normally distributed (K-S = .067, p < .01), the Mann-Whitney U test compared scores between non-clinical and clinical populations. Post hoc analyses examined power and effect size. Configural, metric, scalar, and strict invariance analyses compared both populations. The better-fitting population served as the base for refining the other. The final versions and their reliability were assessed using Cronbach's α and McDonald's ɷ, as well as the percentage of explained variance.

Phase II - Convergent and predictive validity; sensitivity and specificity

Participants

The sample included 345 clinical adolescents (73.6% females), aged 13 to 18 years (Mage = 15.2, SDage = 1.4). Adolescents with adequate comprehension skills, allowing them to understand and complete the items of the scale, were invited to participate. 46.2% of the sample were hospitalized with an average stay of M = 7.6 days (SD = 6.4), and 53.8% received outpatient care. Most (55.4%) had three or four psychiatric diagnoses, predominantly of a mixed type (internalizing and externalizing; 52.4%). 78% of the sample reported having attempted suicide at least once in their lifetime, with the majority having made five attempts (76%). The average age of onset was M = 12.6 years (SD = 2.3).

Settings

Hospital Psiquiátrico Infantil “Dr. Juan N. Navarro” (HPIJNN).

Measures

Acquired Capability for Suicide Scale for clinical adolescent population (ACSS-AP). A version derived from Phase I of this study.

Interpersonal Needs Questionnaire (Silva et al., 2018). The scale comprises 15 items with seven response options, grouped into two factors: Thwarted belongingness and Perceived burdensomeness. In this sample, nine items demonstrated effective performance: Five for the first factor and four for the second. Psychometric properties for this sample were α = .87 for the overall scale, .93 for Perceived Burdensomeness, and .80 for Thwarted Belongingness; CMIN/DF = 1.65, CFI = .993, RMSEA = .041, pClose = .73.

Impulsivity Scale (Climent et al., 1989; González-Forteza et al., 1997). Five items that assess the frequency of impulsive traits on a scale ranging from five to 20 points. The reliability was α = .76, and the fit indices were CMIN/DF = 2.25, CFI = .98, RMSEA = .056; pClose = .347.

Beck Suicide Ideation Scale (Artasánchez-Franco, 1999; Beck & Steer, 1993). Items one, two, three and five measured passive suicidal ideation (Forkmann et al., 2021); their psychometric properties were α = .88; CMIN/DF = .325, CFI = 1.000, RMSEA = .000, pClose = .880. Items four, six, seven, eight and nine measured active suicidal ideation (Forkmann et al., 2021) with psychometric properties of α = .86; CMIN/DF = 1.358, CFI = .999, RMSEA = .030, pClose = .60.

Lifetime Suicide Attempts: A dichotomous and continuous variable measured by the questions: “¿alguna vez te has herido, cortado, intoxicado o hecho daño a propósito con intención de quitarte la vida?” [have you ever purposely hurt, cut, intoxicated, or harmed yourself with intent to take your own life?] and “¿cuántas veces te has herido, cortado, intoxicado, o hecho daño a propósito para tratar de quitarte la vida?" [How many times have you intentionally harmed, cut, poisoned, or injured yourself in an attempt to take your own life?] (CIP-DERS; González-Forteza & Jiménez-Tapia, 2019).

Procedure

Adolescents and their legal guardians who agreed to participate in the study provided their assent and informed consent, respectively. The scales were administered to a total of 396 adolescents; those who were hospitalized received a printed version, while those in outpatient care completed the electronic version.

Statistical analysis

We used IBM SPSS® version 26. Univariate assumptions were checked for each variable in the ACS nomological network using specified psychometric instruments. Outliers for lifetime suicide attempts (identified as z-scores ≥ 3) were removed, resulting in a final sample of 345 adolescents. Multivariate analyses included a predicted vs. residual plot to ensure no outliers affecting the distribution. Both univariate and multivariate analyses assumed normality (skewness and kurtosis ≤ 2; Miles & Shervin, 2011).

The Pearson Product-Moment coefficient was obtained to confirm a positive association between ACS, measured with the proposed scale, and the rest of the constructs as evidence of convergent validity. Predictive validity was assessed using simple linear regression between ACS and lifetime suicide attempts, examining model significance and explained variance. Sensitivity and specificity analyses were conducted using a binomial logistic regression model, with the same dependent variable measured dichotomously.

Significance was examined using the Hosmer & Lemeshow test. The overall classification accuracy, the percentages of correctly classified positive and negative cases, and the explained variance percentages were evaluated using Cox and Snell and Nagelkerke indices.

Ethical considerations

This study was conducted following the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. Recruitment, consent, and data collection procedures were approved by the Research Ethics Committee of the Hospital Psiquiátrico Infantil “Dr. Juan N. Navarro” (HPIJNN), in Mexico (approval number PI3/01/0921).

RESULTS

Phase I - Confirmatory Factor Analysis and reliability

We performed four CFA, one for the original items and factor structure (Version 1), and three for different adapted versions. Version 2 excluded items from the original scale that did not meet minimum factor loadings and explained variances. Version 3 excluded newly created items from the item pool suggested by the expert judges during the scale adaptation period, to observe their behaviour with the rest of the items and their corresponding factor and identify those that were not functioning correctly. Version 4 excluded newly created items that did not meet expected values.

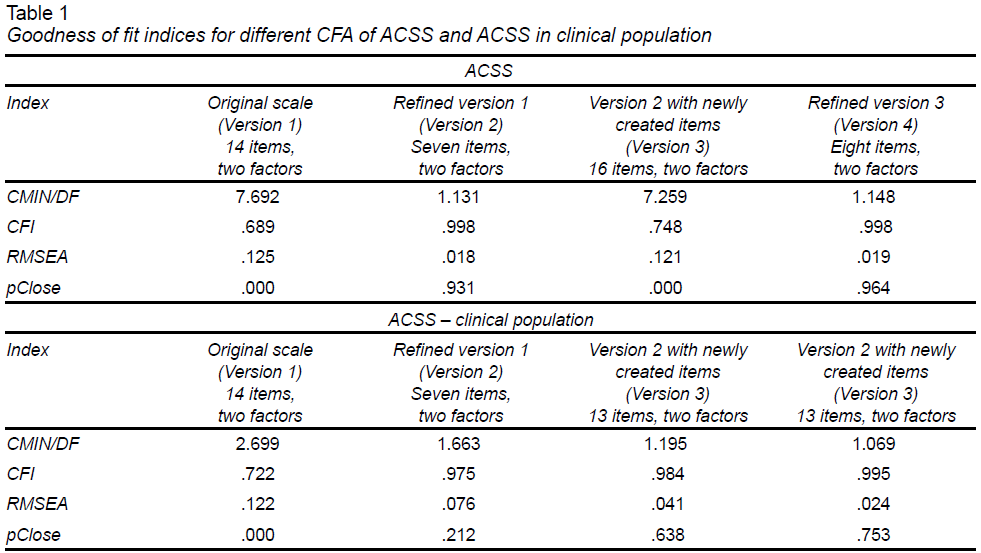

The first part of the Table 1 presents the factor solutions and goodness-of-fit indices for the four versions for comparison.

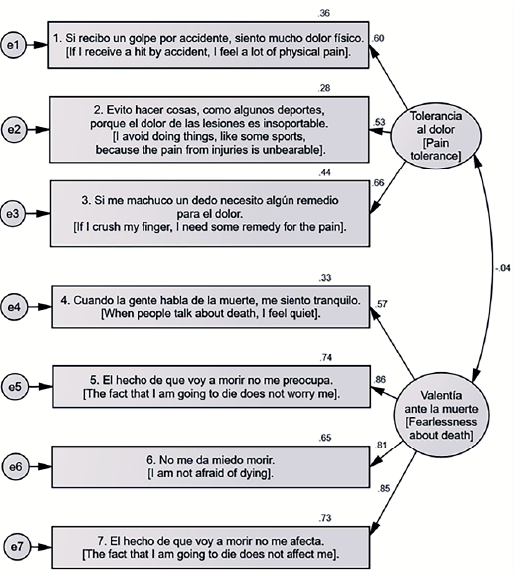

Given the minimal differences in goodness-of-fit indices between Version 2 and Version 4, and the preference for a parsimonious structure, Version 2 was chosen as the base model for the CFA. This model, shown in Figure 1, will be referred to as ACSS – A.

The Mann-Whitney U test compared the mean ranges of the non-clinical and clinical population for the total ACSS – A score. Results indicated a statistically significant mean difference (U = 10985, p < .001), with the clinical population (Mean Range = 276.80) scoring higher than the non-clinical population (Mean Range = 192.10). Post-hoc tests showed a power of 1 – β = .99 and an effect size d = .72, indicating a major difference in the clinical population.

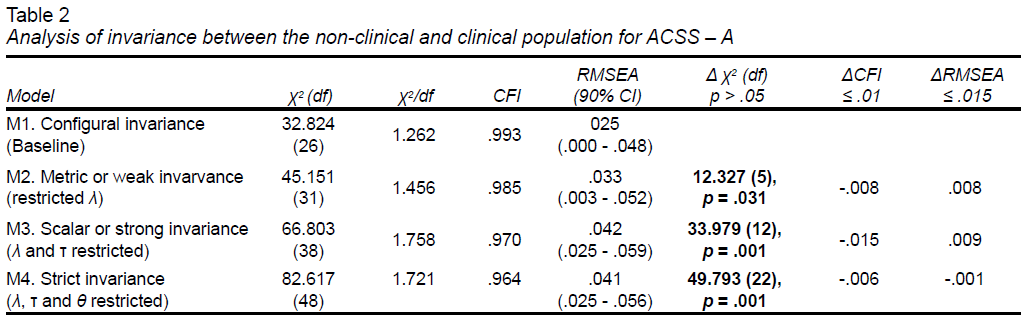

The invariance analysis results between the non-clinical and clinical populations are in Table 2. The significant Chi-square difference (Δχ2) indicated a lack of invariance between both populations in metric, scalar, and strict models. In the non-clinical sample, the regression weights of each item were significant, but not in the clinical sample.

Therefore, a new factor structure was needed for the clinical population. The scale’s reliability for the non-clinical population was α = .669 (ɷ = .71) for the total scale, α = .663 (ɷ = .63) for Pain Tolerance, and α = .849 (ɷ = .86) for Fearlessness about death, explaining 50.6% of the variance.

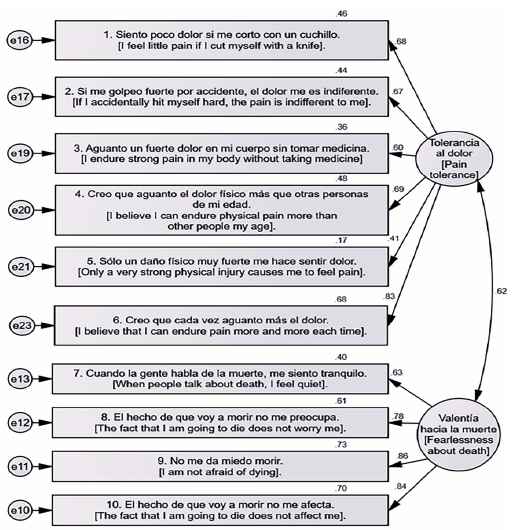

The second part of Table 1 displays the goodness-of-fit indices for the original scale and various item-filtered versions for the clinical population. Version 4, which exhibited the best fit indices, was chosen as the final scale for the clinical population (ACSS – AP, Figure 2). This version consisted of 10 items: six for Pain Tolerance and four for Fearlessness about death. The overall reliability was α = .869 (ɷ = .87), with α = .80 (ɷ = .81) for Pain Tolerance and α = .86 (ɷ = .86) for Fearlessness about death, explaining 52.6% of the variance.

Phase II – Convergent and predictive validity; sensitivity and specificity

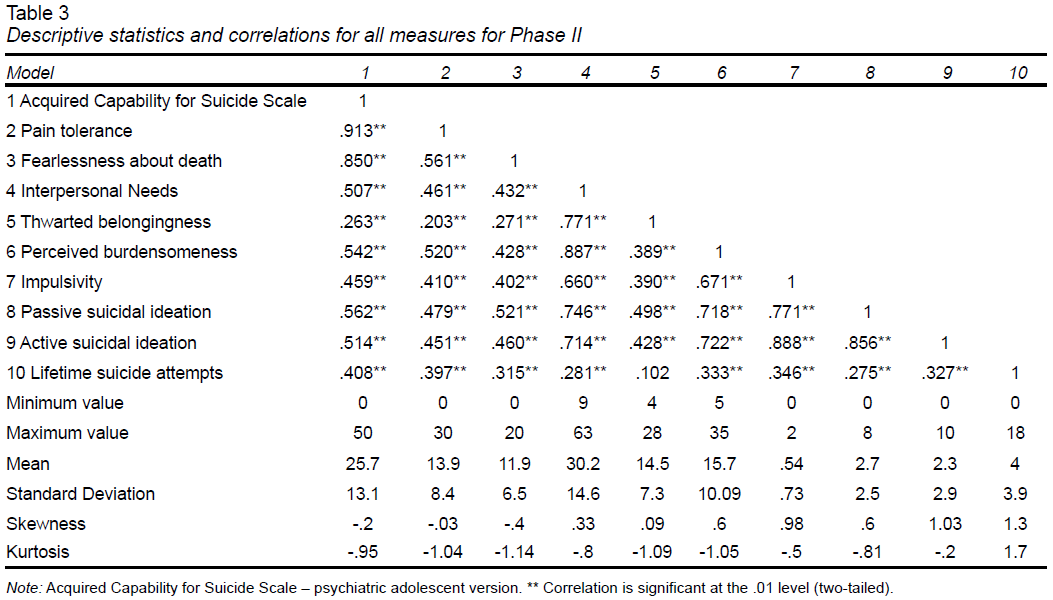

Table 3 presents the descriptive statistics for each variable in the nomological network of ACS, including overall scales and their factors. The skewness and kurtosis for each variable were approximately 1, appropriate for normal distributions (Miles & Shervin, 2011). Pearson's correlation coefficients indicate statistically significant positive associations between constructs (p < .01), except for Thwarted belongingness with lifetime suicide attempts (p = .102).

The INQ and ACSS – AP scales exhibit high to very high correlations with their factors (r > .7; Cohen, 1988), as theoretically expected. ACSS – AP correlations with other constructs are moderate (r > .4; Cohen, 1988), with Thwarted belongingness having the lowest correlation (r = .3), although all statistically significant (p < .01). High correlations are also observed between INQ and impulsivity, active and passive suicidal ideation, with Perceived burdensomeness predominating over Thwarted belongingness (r > .6).

Simple linear regression showed ACS significantly predicted lifetime suicide attempts (β = .40, t = 8.3, p < .001, 95% CI [.091-.15]) in adolescents with psychiatric disorders, explaining 16.4% of the variance (F(1,343) = 68.44, p < .001).

The binomial logistic regression model was statistically reliable (X2 = 49.252, DF = 1, p = .000), and the Hosmer & Lemeshow test indicated a good fit to the data (X2 = 11.792, DF = 8, p = .161). The model explained between 13.3%Cox and Snell and 20.9%Nagelkerke of the variance in the occurrence of lifetime suicide attempts among adolescents. The overall correct classification was 80.3%, with the model correctly predicting 96% of cases in which individuals had attempted suicide at least once in their lifetime and 18.6% of those without suicide attempts.

DISCUSSION AND CONCLUSION

This study aimed to establish the psychometric properties of the Acquired Capability for Suicide Scale (Rangel-Villafaña et al., 2023) in Mexican adolescents, exploring its equivalence across clinical and non-clinical populations.

A significant finding was the distinct structuring of Pain Tolerance between these groups. In the non-clinical sample, the items phrased in the same direction as the original scale to measure non-tolerance to pain performed better (e.g., “Si recibo un golpe por accidente, siento mucho dolor físico” [If I accidentally receive a blow, I feel a lot of physical pain]), whereas the clinical sample responded more favorably to items assessing pain tolerance, particularly those depicting severe pain exposure situations (e.g., “Sólo un daño físico muy fuerte me hace sentir dolor” [Only very strong physical harm makes me feel pain]).

The difference in item phrasing was supported by feedback from clinical respondents, who normalized situations involving minor injuries or continuing physical activities despite pain. This suggests lower sensitivity to minor pain in they, likely due to their increased exposure to intense pain situations such as self-inflicted burns or suicide attempts (Van Orden et al., 2008; Van Orden et al., 2010), resulting in a larger effect size, highlighting the need for tailored item formulation. It is important to note that measuring pain tolerance through self-report can be complex as it is subjective and influenced by perception biases; objective measures are suggested as a more reliable method, such as electrical stimulation, the cold pressor task, thermal stimulators, or mechanical pressure devices. Among these, electrical stimulation has demonstrated greater objectivity, reliability, and patient-friendliness in assessing pain (Edwards & Fillingim, 2007; Wachtel et al., 2015; Wagemakers et al., 2019).

Two items performed poorly in both samples: "Evito participar en peleas porque no soporto el dolor físico que generan" [I avoid getting into fights because I can't stand the physical pain they generate], where adolescents noted reasons other than pain for avoiding fights, and "Necesito tomar medicamentos para quitar algún dolor físico" ["I need to take medication to relieve any physical pain"], which was redundant with item three (Figure 1) and thus eliminated.

Regarding Fearlessness about death, the items that performed well were consistent across both non-clinical and clinical populations, indicating a stable manifestation of the construct. These items assessed emotions related to death, such as fear or worry. Two removed items focused on the act of dying rather than the associated emotions, (e.g., “Podría matarme a mí mismo si quisiera” ["I could kill myself if I wanted to"]. Although this item could theoretically be considered highly relevant to the construct, its performance within the overall model was suboptimal, likely because the other items were measuring emotions related to death rather than the act of dying itself. According to Hinkin (1995), at least three items are needed for them to cluster together. Probably including more items related to the act of dying might group them into another factor (Rimkeviciene et al., 2017), potentially forming a subdimension or a more precise measure. In the German version (Wachtel et al., 2014), this item did not contribute to Fearlessness about death but was retained as a single item for ACS. Ribeiro et al. (2014) suggested that items assessing Fearlessness about one's own death, rather than death in general, may better capture the construct.

Furthermore, several items that did not effectively measure Fearlessness about death were removed due to their focus on other constructs. E.g., “Imaginar mi muerte no me asusta” [Imagining my death does not scare me] primarily reflects suicidal ideation, while “El miedo a morir me inquieta” [The fear of dying worries me] is worded in reverse and is not aligned with the other items. “Me asusta el dolor asociado a morir” [I'm scared of the pain associated with dying] primarily assesses pain related to death.

It is also important to consider the cultural context in Mexico, where death is celebrated during Día de los Muertos, viewed traditionally with humor and satire. Consequently, the concept of death may not evoke fear among Mexicans. Therefore, items like “La posibilidad de morir me causa ansiedad” [The possibility of dying causes me anxiety] or “Pensar en mi propia muerte me causa curiosidad” [Thinking about my own death causes me curiosity] were not effective in either sample. The latter item also overlaps closely with suicidal ideation. This leads to the need to consider cultural influences in specific populations in order to determine the functioning of items intended to assess the construct.

It is worth mentioning that, in addition to the theoretical inconsistencies identified through the qualitative analysis of the eliminated items, these items did not exhibit statistically satisfactory performance. Consequently, their contribution to the total variance of the model was minimal or even detrimental, which justified their removal.

The reliability of both the full scale and Pain Tolerance scale was lower in the non-clinical sample. This suggests that the scale may lack sensitivity in detecting ACS in adolescents without significant suicidal behavior or with lower levels of it (Rogers et al., 2021). In contrast, adolescents with psychiatric disorders who often experience more severe and frequent pain, showed higher reliability for the scale and this factor (Van Orden et al., 2008; Van Orden et al., 2010). Fearlessness about death exhibited greater stability across both populations, with higher reliability.

The ACSS – AP scale demonstrated a positive and moderately strong relationship (Cohen, 1988) with theoretically expected constructs (Van Orden et al., 2008; Van Orden et al., 2010; Van Orden et al., 2015), indicating convergent validity. Thwarted belongingness and perceived burdensomeness showed statistically significant moderate associations, consistent with findings in clinical adolescent samples (King et al., 2019; Horton et al., 2015). Surprisingly, the correlation between ACS and lifetime suicide attempts was higher than previously reported (r = .09, p = .027; Chu et al., 2017); however, it is crucial to note that only four studies included adolescents in this meta-analysis.

Impulsivity is identified as a contributing factor to the ACS (Van Orden et al., 2010), although Bender et al. (2011) and Witte et al. (2008), suggest it does not directly relate to ACS. Instead, impulsive individuals may encounter more painful and provocative events (PPEs), facilitating capability acquisition. This study found a direct, significant and moderate correlation between impulsivity and ACS (Cohen, 1988). However, this does not imply causation, and further exploration through mediation models involving PPEs is warranted to better elucidate their relationship.

Regarding suicidal ideation, studies generally do not differentiate between passive and active ideation when evaluating the IPTS model (Baertschi et al., 2017). Nonetheless, the results reported here align with those for general suicidal ideation in adolescents (Horton et al., 2015; King et al., 2019).

Joiner (2005) proposes that the ACS becomes significant when interacting with thwarted belongingness and perceived burdensomeness (Van Orden et al., 2008, 2010). While research indicates variability in its direct prediction of suicide attempts (Chu et al., 2017), the theory emphasizes ACS as a predictor of future, rather than past attempts. This study, which examines past attempts, serves as a proxy measure aligned with theoretical propositions.

This study found a direct contribution to variance of 16.4%, consistent with satisfactory results reported in 40% of cross-sectional studies included in Chu et al.’s meta-analysis (2017), and other studies with clinical adolescent samples (Horton et al., 2015; Czyz et al., 2014). While the explained variance is small, it is important to consider other factors established by the theory in prediction that were not included in the linear regression model (e. g. three-way interaction between thwarted belongingness, perceived burdensomeness and acquired capability for suicide; Joiner et al., 2009). Consequently, the explained variance should not be viewed in isolation but rather as a reflection of the instrument’s contribution within a broader explanatory framework. Moreover, predicting future attempts requires conducting a longitudinal study, which can be considered a potential line of future research.

Regarding the sensitivity and specificity test, while a considerable correct classification rate was obtained (80.3%), particularly with a high sensitivity rate (96%), it is important to note that the analysis was conducted using the occurrence of suicide attempts among adolescents as the dependent variable. This variable serves as a proxy, given the absence of a gold standard for comparative evaluation of the instrument. An analysis using ROC curves would be highly recommended if such a criterion were available.

This study has other limitations, one of them is the absence of evidence regarding divergent and discriminant validity. Future research should incorporate additional scales that are part of the nomological network of ACS to confirm that the scale exclusively measures the construct of interest.

Additionally, in the Fearlessness about death factor, items assessing emotions related to death were included, while those addressing the act of dying were excluded. To mitigate this limitation, we recommend including more items that focus on the act of dying itself, aligning with suggestions from prior research (Wachtel et al., 2014; Ribeiro et al., 2014; Rimkeviciene et al., 2017).

It is also important to note that in Phase I, the sample was limited to students, which means that the representativeness of adolescents in the study may be affected by the exclusion of those without access to education. Similarly, in both phases, a high percentage of participants were women, and specifically in Phase II, participants were exclusively recruited from a psychiatric hospital. The higher prevalence of women aligns with the current epidemiology of suicide-related behavior (Borges et al., 2019). However, the representativeness of the population and the generalizability of the findings are limited to contexts where the severity of the phenomenon is higher, excluding community samples or those in primary care settings.

Despite these limitations, this study provides a valuable contribution by proposing a valid and reliable scale for measuring ACS in Mexican adolescents, particularly in psychiatric and high-risk populations, which has not been previously documented in the literature. Given the sustained increase in suicide attempts among adolescents in Mexico, and the urgent need to implement actions to reduce these figures, this tool presents itself as a valuable resource to, initially, begin gathering evidence on the functioning of the IPTS in this population (Stewart et al., 2015). If explanatory models of suicide attempts are developed with a robust level of evidence, public resources could be directed towards targeted therapeutic interventions, thus achieving greater effectiveness for those in need.

Finally, according to invariance analysis, this study provides evidence for the non-generalization of the scale tested in the general population. Therefore, understanding the phenomenon should differentiate between those with a history of lifetime suicide attempts and those without, and the tools should be specific to each subgroup.