INTRODUCTION

According to the World Migration Report, there were 281 million international migrants in 2020, meaning that 3.6% of the world´s population live outside their country of origin, 108 million more than in 2000. Fifteen years ago, there were seven million international migrants from Latin America and the Caribbean, a figure that has since risen to 15 million. The number of migrants transiting through South and Central America to the United States has also increased (McAuliffe & Oucho, 2024). The main international migration destination is the United States while the largest migration corridor to that country is in Mexico, with nearly 11 million people in transit (McAuliffe & Triandafyllidou, 2022).

Migrants from Central and South America must travel through several countries before arriving in the United States. International studies have shown that crossing one or more international borders to reach the final destination poses major challenges since migrants in transit (MIT) must often take dangerous routes to avoid detention, facing discrimination, violence, torture, kidnapping, human trafficking, enforced disappearance, and other life-threatening experiences (Ben Farhat et al., 2018; Gargano et al., 2022; Guarch-Rubio et al., 2021).

Migration through Latin America to the United States is driven by social vulnerability characterized by conflicts, violence, poverty, and unemployment (Hernández Alvarado et al., 2022; Santana-Hernández, 2005). The history of migration in Latin and Central America occurred in stages. In the beginning, it was due to armed conflicts in the 80s, particularly in Cuba and Nicaragua, triggering the first wave of migration in the region. In 1990, it was caused by economic factors when the social and political climate stabilized. Migration is currently caused by the violent social conditions and climate of adversity prevailing in Central and South America (Aruj, 2008; Reichman, 2015).

Social conditions in sending countries and the tightening of migrant reception policies in the United States (such as the Migrant Protection Protocols) suggest that nations that were previously crossing points will become mandatory destinations for MIT. For example, Mexico is becoming a destination country for international migrants: between 2000 and 2020 the immigrant population increased by 123%. Likewise, the number of migrants in an irregular situation through Mexico has increased significantly, from 131,445 in 2018 to 782,176 in 2023 (Organización Internacional de las Migraciones, 2023). This migratory situation creates new needs for diagnosis and care.

Evidence suggests that MIT who either cross Mexico or reach the U.S.-Mexico border have experienced more traumatic experiences than the general population and when they manage to cross the border, they have mental and behavioral disorders, such as post-traumatic stress, major depressive episodes, anxiety, and stress (Infante-Xibille et al., 2015; Venta, 2019).

According to an umbrella review conducted by the World Health Organization, challenging situations associated with migration constitute a risk factor for developing mental disorders. These include exposure to adversity and potentially traumatic events as well as the lack of security and difficulty covering basic needs (World Health Organization, 2023). However, this review did not provide specific information on mental health issues in MIT.

Despite the growing global attention to the mental health of migrant populations, the specific challenges faced by migrants in transit (MIT) remain understudied. While extensive research has focused on the mental health of settled refugees and asylum seekers, especially in Europe, North America, and Australia, far less is known about those who are still in transit—individuals navigating prolonged journeys, often under conditions of extreme vulnerability. The scarcity of evidence is even more marked in the Americas, where the world's largest migratory corridor is located. This knowledge gap hampers the development of effective, context-specific interventions and leaves a critical population without adequate mental health support. Addressing this gap is therefore essential to ensuring a more comprehensive and equitable global response to migration.

Having evidence about the extent to which mental health problems have been explored in migrants in transit in the largest migratory corridor in the world will make it possible to identify information gaps as well as elucidate the needs of this population. This scoping review aims to identify and describe the evidence on mental health and substance use among migrants in transit through Latin America to the United States.

METHOD

This study was conducted using the scoping review methodological recommendations put forward by the Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI) (Aromataris & Munn, 2020) and followed the guidelines of the Preferred Reporting Items for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR) to guide reporting ( Tricco et al., 2018).

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

The inclusion criteria and review question were developed using the Population, Concept, and Context (PCC) framework, as recommended by the JBI methodology for scoping reviews (Aromataris & Munn, 2020). Studies were eligible if they focused on any aspect of mental health among migrants of any age and sex in transit through Latin American countries on their way to the United States. Eligible publications had to be original research articles published in English, Spanish, or Portuguese between January 2018 and May 2024—a timeframe selected due to the documented increase in irregular migration flows in the region, particularly through Mexico. The search was conducted on June 4, 2024. We included studies employing quantitative, qualitative, or mixed-method designs. Studies were excluded if they focused on migrants who were already residing in the United States or if they were review articles (i.e. narrative or systematic reviews).

Information sources

EBSCO, PubMed, Scielo and SAGE were searched as well as the references in the included studies.

Search strategy

The following terms were used and combined to be used in each database: (Transients and Migrants OR Transmigrant OR Intercepted journey OR Interrupted transit OR Migrants in transit OR Migrants in transit through Mexico OR Migrants in transit thorough Latin America OR Migrant journey OR Migration journey OR Persons in mobility through OR Migrant journey through OR Migratory Transit) AND (Mexico OR Americas OR “South America” OR “America” OR “Latin America“ OR “Central America" OR “Migrant Mexico corridor”) NOT (Europe NOT Asia NOT Australia NOT Africa) AND (Addictions OR Substance use disorders OR Substance abuse OR illicit drugs OR Designer Drugs OR Psychiatric disorders OR Mental disorders OR Mental health OR Migrants’ mental health in transit OR Behavior, Addictive OR Substance-Related Disorders OR illicit drugs OR Designer Drugs OR Mental Disorders OR Mental Health OR Stress Disorders, Post-Traumatic OR Depression OR Anxiety).

Selection of studies

Studies were independently selected by three researchers using a checklist derived from the selection criteria, while disagreements were discussed and resolved by consensus. The process began by reviewing titles to identify duplicate articles and then proceeding to make an initial selection based on the information contained in the abstract. The full text of the preselected articles was subsequently reviewed.

Data extraction

To analyze the information from the included studies, we developed two structured data extraction tables—one for qualitative studies and another for quantitative studies. In the case of mixed-method studies, qualitative and quantitative data were recorded in the respective table. These tools were constructed in keeping with the JBI guidelines developed by Aromataris & Munn (2020), and pilot tested to ensure clarity and understanding.

For the categorization of findings, we adopted an inductive basic qualitative content analysis approach, as recommended by Pollock et al. (2023). This involved an initial phase of open coding, where relevant data excerpts were la beled with descriptive codes. These codes were then grouped into higher order categories through iterative team discussions, facilitating the systematic organization of findings. The first level of classification was the methodological design of the studies (qualitative, quantitative, or mixed method), followed by thematic categories derived from the coded content.

RESULTS

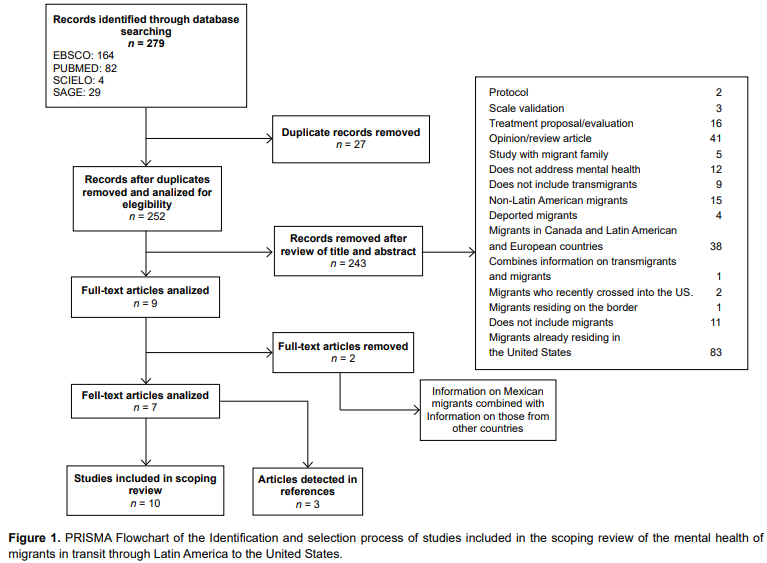

Two hundred and seventy-nine articles were identified, 27 duplicate records were removed, and 243 records were removed following a review of their titles and abstracts. Seven were found to meet the criteria for analysis (Alquisiras Terrones & Zapata Aburto, 2022; Altman et al., 2018; Berenzon-Gorn et al., 2023; Cruz Piñeiro & Ibarra, 2022; Laughon et al., 2023; Rodríguez, 2022; Soria-Escalante et al., 2022) and another three (Cano Collado et al., 2021; Lemus-Way & Johansson, 2020; Silverstein et al., 2021) were identified by checking their references. A total of 10 articles were analyzed ( Figure 1).

Characteristics of included studies

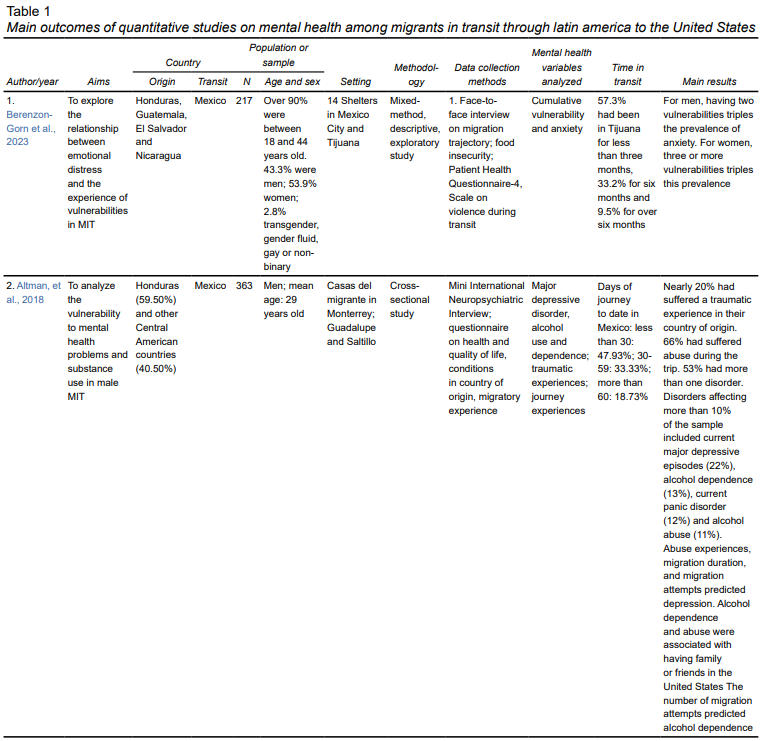

Most of the articles were published in 2022 and based on qualitative studies. Two studies included children (Alquisiras Terrones & Zapata Aburto, 2022; Berenzon-Gorn et al., 2023), and two reported the average ages of participants: 29 and 33.5 years respectively (Altman et al., 2018; Laughon et al., 2023). Three articles included women only (Laughon et al., 2023; Lemus-Way & Johansson, 2020; Soria-Escalante et al., 2022); one analyzed data on transgender, gender fluid, gay and non-binary individuals in addition to men and women (Berenzon-Gorn et al., 2023) while the one conducted by Altman et al. only examined data on men (Altman et al., 2018).

In all the studies (Alquisiras Terrones & Zapata Aburto, 2022; Altman et al., 2018; Berenzon-Gorn et al., 2023; Cano Collado et al., 2021; Cruz Piñeiro & Ibarra, 2022; Laughon et al., 2023; Lemus-Way & Johansson, 2020; Rodríguez, 2022; Silverstein et al., 2021; Soria-Escalante et al., 2022), data collection mainly took place in shelters, migrant homes, makeshift camps, public spaces such as cafeterias, benches, the land adjacent to railroad tracks and plazas. One study analyzed the legal declarations and forensic medical affidavits of refugee seekers staying in Mexico (Silverstein et al., 2021). None of the studies were conducted in settings associated with migration authorities or governmental assistance programs.

All the research (Alquisiras Terrones & Zapata Aburto, 2022; Altman et al., 2018; Berenzon-Gorn et al., 2023; Cano Collado et al., 2021; Cruz Piñeiro & Ibarra, 2022; Laughon et al., 2023; Lemus-Way & Johansson, 2020; Rodríguez, 2022; Soria-Escalante et al., 2022), except one (Silverstein et al., 2021), was conducted in Mexico with migrants from Honduras, Guatemala, El Salvador, and to a lesser extent Nicaragua, Venezuela, Haiti, and Cuba. Two qualitative studies (Cruz Piñeiro & Ibarra, 2022; Laughon et al., 2023) included information from three Mexican participants, but because of the quantity and nature of the information they contributed to the subject of this review, it was decided to analyze them.

With respect to ethical guidelines, two studies did not report approval by any ethics committee (Alquisiras Terrones & Zapata Aburto, 2022; Rodríguez, 2022). These two studies also failed to mention the existence of written or verbal informed consent.

Altman et al. were the only authors to report the length of time in transit or the duration of the journeys undertaken (Altman et al., 2018). Three studies reported the time the MIT had been at the interview site or the time that they had spent in Mexico (Berenzon-Gorn et al., 2023; Cruz Piñeiro & Ibarra, 2022; Laughon et al., 2023). The main characteristics together with a summary of their results are given in Tables 1 and 2.

Mental health

The evidence analyzed reveals a complex, multifaceted picture of mental health among migrants in transit through Mexico. Across the studies, a broad range of psychological effects were reported, including anxiety, depression, psychological distress, sadness, anger, hopelessness, constant worry, and trauma-related symptoms. These mental health outcomes appear to be closely related to the precarious, often violent conditions experienced during transit, as well as the prolonged uncertainty surrounding their legal status and future (Alquisiras Terrones & Zapata Aburto, 2022; Altman et al., 2018; Berenzon-Gorn et al., 2023; Cano Collado et al., 2021; Cruz Piñeiro & Ibarra, 2022; Laughon et al., 2023; Lemus-Way & Johansson, 2020; Rodríguez, 2022; Silverstein et al., 2021; Soria-Escalante et al., 2022).

Common risk factors and conditions during transit

Some studies highlighted the vulnerable conditions experienced throughout the migration journey (Berenzon-Gorn et al., 2023; Laughon et al., 2023; Rodríguez, 2022; Soria-Escalante et al., 2022). These include exposure to violence, whether physical, sexual (Soria-Escalante et al., 2022), symbolic, or structural, committed by either state or non-state actors; abuse by authorities or criminal groups, including extortion, physical mistreatment, and psychological persecution; discrimination, based on migrant status, gender identity, or ethnicity, particularly for racialized and LGBTQ+ migrants; food insecurity and lack of shelter (Laughon et al., 2023), which exacerbate stress, fatigue, and feelings of helplessness; and uncertainty and prolonged waiting times, which contribute to feelings of entrapment and a lack of control over one’s circumstances (Berenzon-Gorn et al., 2023; Rodríguez, 2022).

Experiencing several of these conditions was strongly associated with heightened levels of psychological distress and increased prevalence of anxiety and depressive symptoms. Research indicates that gender- and identity-based discrimination compounds these effects, placing transgender individuals and women at particular risk for mental health deterioration (Berenzon-Gorn et al., 2023; Soria-Escalante et al., 2022).

Among the few quantitative studies available, Altman et al. (2018) reported the prevalence of specific psychiatric disorders in a sample of MIT: the four most prevalent disorders were current major depressive episodes (22%), alcohol dependence (13%), current panic disorder (12%) and alcohol abuse (11%).

In addition, 53% of the sample met the diagnostic criteria for more than one mental disorder. The likelihood of presenting with depressive symptoms increased with both the length of the migration journey and exposure to abuse. Importantly, individuals who had a job waiting for them in the United States were significantly less likely to present with depressive symptoms, suggesting that a sense of future stability may act as a protective factor (Altman et al., 2018).

Just under 20% of participants reported having suffered a traumatic experience in their country of origin prior to emigrating while 66% reported having been abused (by authorities, traffickers and/or civilians) during their northbound journey (Altman et al., 2018).

Gendered and identity-based vulnerabilities

A critical theme in the literature is how mental health challenges are shaped by gender and sexual identity. Transgender migrants face a dual burden of discrimination: as migrants and as gender minorities. Many of them report being forced to pass as men to avoid targeted violence, a strategy that reproduces the very repression and invisibility they sought to escape by migrating. This identity suppression contributes to deep psychological strain and internal conflict.

Women in makeshift camps or shelters frequently reported living in a constant state of fear, hypervigilance, anxiety, and sleep deprivation due to the pervasive insecurity (Laughon et al., 2023). Their narratives reveal the continuous threat of sexual violence, leading many to adopt invisibility as a survival strategy (Soria-Escalante et al., 2022). However, some studies also noted that women developed informal protection networks with others in similar circumstances, which served as an emotional buffer and source of sisterhood (Soria-Escalante et al., 2022).

Psychological sequelae of migration conditions

Qualitative findings underscore the role of structural, symbolic, and everyday violence in shaping mental health outcomes. The study by Rodríguez (2022) described how these forms of violence intersect to produce a state of self- invisibilization, in which migrants deny or suppress their emotional and physical needs to survive hostile contexts. Some migrants reported preexisting childhood trauma, substance use as a coping mechanism, and the development of behavioral adaptations in response to chronic exposure to risk.

The psychological burden becomes especially acute for migrants traveling with children. Caregiving under conditions of extreme uncertainty increases emotional distress and feelings of powerlessness, as noted by Berenzon-Gorn et al. (2023).

Mental health during the COVID-19 pandemic

The COVID-19 pandemic exacerbated the psychological stressors faced by MIT. In addition to the fear of infection, migrants experienced heightened distress due to overcrowding in shelters, social isolation, and a sense of abandonment by immigration authorities (Cruz Piñeiro & Ibarra, 2022). The principal mental health stressors during this period were not only linked to the virus itself, but to the suspension of migration plans, prolonged stagnation, and the perceived collapse of institutional support.

Accidents and existential impact

A particularly harrowing context for psychological suffering was described in the study by Alquisiras Terrones & Zapata Aburto (2022) exploring the experiences of migrants who suffered amputations after accidents while riding La Bestia, the freight train many migrants use to travel north. These individuals reported profound grief, existential questioning, and the collapse of their migration aspirations. Nevertheless, some reinterpreted their suffering through spiritual or religious frameworks, constructing narratives of resilience and divine purpose as a way to regain meaning and agency in the aftermath of traumatic experiences.

Resilience and coping strategies

Despite the overwhelming stressors, some studies emphasized the role of resilience in shaping mental health outcomes. Religion, spirituality, personal goal-setting, and social or institutional support were cited as key protective factors (Lemus-Way & Johansson, 2020). These sources of strength were associated with reduced occurrence of psychosomatic symptoms such as fatigue, insomnia, headaches, and anxiety (Cano Collado et al., 2021). Resilience functioned not only as an individual trait but as a dynamic process sustained through interpersonal relationships and collective practices (Cano Collado et al., 2021; Lemus-Way & Johansson, 2020).

Post request phase

Whereas most studies focus on the transit period, the research by Silverstein et al. (2021) examined the post-request phase and found continued mental health deterioration among MIT waiting in Mexico. Psychological sequelae included anxiety, depression, post-traumatic symptoms, and even thoughts and behaviors related to suicide. These mental health symptoms were identified after the asylum application, rather than during the journey itself, suggesting that the uncertainty and systemic exclusion endured during the post-request phase also perpetuate psychological harm.

Substance use

Only one article (Altman et al., 2018) explicitly inquired about substance use, finding that 13% of the sample had alcohol dependence and 11% abused alcohol. A high number of journey attempts and experience of abuse (torture, persecution, or mistreatment by the community, authorities, or family before emigrating) were significantly associated with greater odds of alcohol dependence. MIT who were ill or required medication were more likely to abuse alcohol than those who were not ill. MIT with family or relatives in the United States were five times more likely to have alcohol dependence and abuse (OR = 4.86 and 5.07 respectively).

DISCUSSION AND CONCLUSION

This scoping review identified ten articles evaluating the mental health and substance use of MIT from Latin America to the United States. Findings show that their health has been poorly evaluated due to several factors faced by both migrants, the health care systems, researchers, and civil society organizations in the countries through which they pass. Reasons include stigma and discrimination, language and cultural barriers, as well as irregular migration status. The constant need to keep moving to reach their intended destination is also a challenge. This factor compounds the difficulty of assessing, diagnosing, and treating this population.

Most of the research analyzed in this review used a qualitative methodology. Further research should include more extensive diagnostic evaluations of mental health, substance use and protective factors such as resilience and coping strategies in migrants in transit thought countries other than Mexico.

All the information analyzed in this review was obtained from MIT through Mexico. Nine of the included studies were conducted in contexts supported by civil society organizations and in public places rather than official or government institutions. This pattern of data collection can be explained by several interrelated factors. First, MIT often travel with irregular migratory status, placing them in a position of increased legal and social vulnerability. Accordingly, they may seek to avoid contact with formal institutions or government actors due to the risk of detention and deportation. Second, several of the qualitative studies included in this review document widespread mistrust of authorities among MIT, rooted in previous experiences of abuse, discrimination, or neglect at the hands of law enforcement or migration officials. These experiences contribute to a climate of fear and reluctance to seek help from state-run services. Consequently, civil society organizations and humanitarian actors often become the primary points of contact for both support and research, as they are perceived as safer, more accessible, and more empathetic environments for MIT. This context not only shapes the conditions under which data on mental health is collected but also highlights the critical role of non-governmental spaces in documenting and addressing the psychosocial needs of migrants in transit through Mexico.

At this point, the question arises as to what type of services are offered in the shelters where MITs are housed and whether these services include mental health care. Answering this question is a challenge for future research.

According to Gargano et al. (2022), transit countries face challenges in covering basic living necessities such as food, shelter and healthcare access. This is the case of Mexico, which does not fulfil the criteria to be considered a safe third country since it fails to meet the standards established by the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees of offering security and guarantees that migrants will not be deported to their countries of origin (Instituto para las Mujeres en la Migración, 2019). The social, economic, and political conditions in Mexico hinder the observance of these guidelines. Nevertheless, the number of asylum requests has grown in the past five years, with 29,631 requests being received in 2018 and 140,812 in 2023 (Alto Comisionado de las Naciones Unidas para los Refugiados, 2023). This has happened even though structural and social violence and organized crime increase migrants' exposure to mass kidnapping, extortion, and human trafficking (París Pombo et al., 2016).

The desire to continue their migratory journey forces MIT to be continually on the move, meaning that there is no community context to welcome them. This makes them a population with characteristics and needs that are difficult to either address or study. Future efforts in transit countries should consider this characteristic.

According to the findings of this review, there is a dearth of information on the mental health of migrants in transit through Latin America to the United States, pointing to the need for further research on this topic.

The analysis of the ten articles included identifying the effects of being in transit on MIT. These included the anxiety, depression, and psychological distress caused by the uncertainty of being able to reach their destination, and the experience of the different types of violence and discrimination suffered in both their countries of origin and during transit in Mexico before reaching the United States.

In the studies analyzed, no significant differences in mental health outcomes were identified based on the migrants’ country of origin. This finding is noteworthy, as it suggests that the psychological distress and mental health symptoms experienced by migrants in transit (MIT) may be more closely related to shared conditions of vulnerability during the migratory journey—such as exposure to violence, uncertainty, precarious living conditions, and lack of access to services—than to specific national or cultural backgrounds. However, the absence of differences by country of origin does not necessarily imply that all migrants experience transit in the same way. Rather, it points to the need for further research to explore how structural and situational factors common to transit through Mexico shape mental health, possibly overriding individual differences based on nationality.

It is important to address this situation and raise awareness of the mental health of MIT to ensure they receive necessary care and protection. This requires the countries through which they transit to develop public policies to address barriers to healthcare access, promote cultural sensitivity, and provide adequate professional, social, and financial resources for their mental health.